This month marks the 40th anniversary of a month of shows by the Grateful Dead that are regarded with awe by their legions of fans. At the core is the night of May 8, 1977, when the band played Cornell University’s Barton Hall and delivered what has long been considered their greatest show. In 2011, the Library of Congress added the Cornell show to the National Recording Registry even though it hadn’t been officially released.

This being the Dead, all the May 1977 shows have been circulating in various unofficial ways for decades. There was even an official box set of some May 1977 shows. But, until now, the Cornell show itself had never seen an official release. A limited-edition box set was put out this month, including a recording of the show along with three others previously unreleased. What is revealed should surprise no one at this point: the Cornell show was nothing special. It was in fact a typical night for the band in this period: sounding no different from other shows, comprising a set list of songs that were the usual suspects from that tour. Yet, this is high praise, because in May 1977, no band was delivering anything like what the Dead were putting on stage.

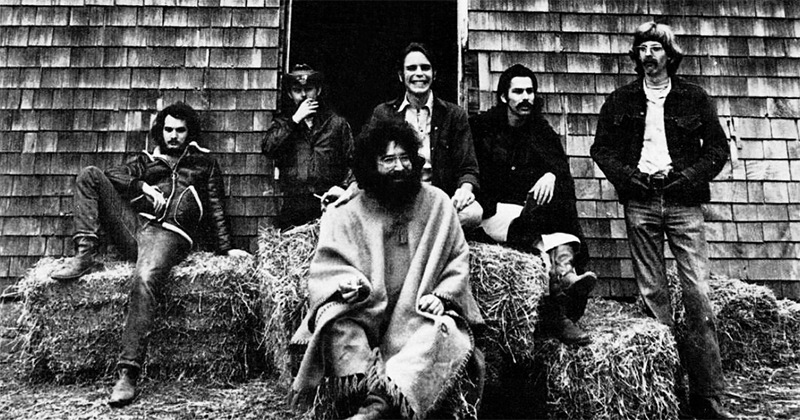

The band’s earlier history explains in part what made them so special. Almost exactly a decade earlier, the Monterey Pop Festival kicked off the Summer of Love and thus the mainstreaming of American counterculture. In addition to introducing American audiences to English stars the Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the festival mostly celebrated the California sound of the time with performances by, among others, Jefferson Airplane, Buffalo Springfield, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Byrds, the Steve Miller Band (a blues group with Boz Scaggs), Mamas & the Papas, Janis Joplin, and the Association. By 1977, the Grateful Dead were among the few of these California acts still going with anything like the same membership. The band had an almost unique opportunity to grow together, expanding on the possibilities offered by that fertile moment in American music.

And grow the band had. Early days, as documented on stage at the Fillmore in 1969, included too-long, mediocre jams on old R&B songs alongside the played-out originals that defined the band as psychedelic warriors. It is a cliché to say the Dead could never capture in the studio the magic of their live performance, but in 1970 the band released two studio masterpieces: Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty. These albums were founding documents of a handful of genres: country rock, Americana, or even (via Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter’s partnership) ’70s California singer/songwriter personae. Less flatteringly, they were also echoed in the gentle sounds of later-’70s soft rock. This is to say that the albums often switch out electric for acoustic guitars, the soloing is kept to a minimum, and the production highlights the harmonies and the craft of the songwriting. No songs on either disc even pass the six-minute mark (by which point “Dark Star” in the band’s stage show was just getting started). There are no drum solos. These are the Grateful Dead songs you hear on the radio: “Truckin’,” “Casey Jones,” “Uncle John’s Band,” and “Sugar Magnolia.”

Also included on those discs are other songs that would remain important to the band’s live shows in the years to come: “Dire Wolf,” “Friend of the Devil,” “New Speedway Boogie,” “Cumberland Blues,” and “Candyman.” They had the sort of melodies you could build on. Two years later, during their first tour of Europe in 1972, the Grateful Dead mixed these songs with a handful of country cover versions (“You Win Again,” “Me and Bobby McGee,” “El Paso”), showing the provenance of the new material alongside the old, extended R&B covers and the psychedelic adventurism. The result was the Grateful Dead’s most legendary tour. Immersive binge listening is the best way to fully understand this band in all their facets; here in 1972 is the music to explore. But it is not the best introduction to the band. That music comes to us five years later, from these concerts in 1977. By then, the Dead had to teach the audience how to appreciate their jams.

So, what was going on when the Dead took the stage at Cornell? Certainly, the band had gone through some changes, including a brief hiatus from touring around 1975. More significantly, founding member Pigpen had died, and drummer Mickey Hart had returned to the band.

But while the Dead had changed some, the culture had changed a lot. In addition to most of their peers having long disbanded, disco and punk were the genres of the times. The radio stations playing Queen and Billy Joel had little use for the Grateful Dead. And even sympathetic young people by 1977 found it hard to access the often dissonant and spacey music the Dead were known to make. While some bumper stickers said “There is Nothing Like A Grateful Dead Concert,” others read “There is Nothing More Boring Than A Grateful Dead Concert.”

The Grateful Dead were now beginning to perform for a false-nostalgia audience of teenagers who missed the hippie movement entirely yet chose to recreate their image of the ’60s by going to the band’s shows and following them on tour: communal-minded, drug-inflected, aspiring to peace and love, tie-dyed, and reeking of incense. This is an audience that may never have heard Moby Grape or the other early peers of the Grateful Dead. It was certainly an audience unlikely to recognize the band’s Merle Haggard and George Jones covers.

But it was a cultural niche and the Dead had it all to themselves. Their audience swelled from theatres to stadiums, and a community in bootleg trading evolved as fans aspired to capture every note played by the band. These bootlegs varied in quality, and a large part of the story of the Cornell concert’s reputation was the early and wide circulation of a high-quality bootleg from the show.

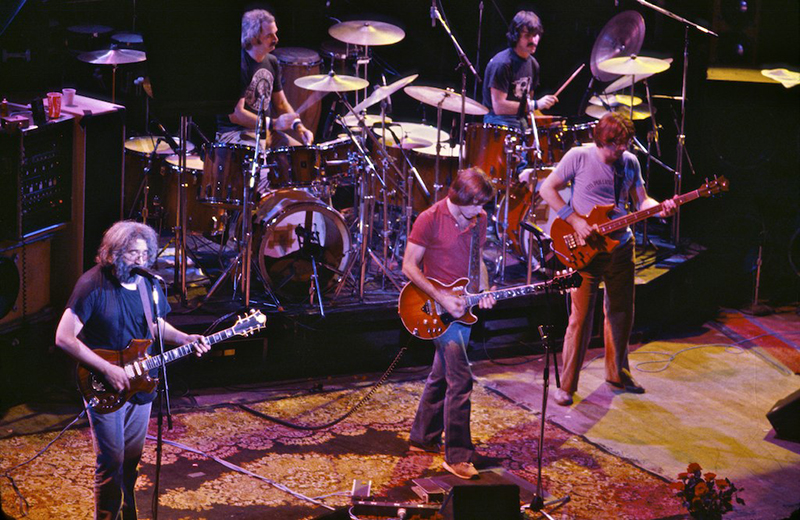

The new releases are even better sounding than those bootlegs. They were made from official tapes, known as Betty Boards, created in real time by a longtime sound engineer named Betty as the band played. Lost for years, these 40-year-old recording tapes do have minor deficiencies;. however, the quality allows for a full appreciation of what was happening on stage. The first thing to notice is that there is less music being made than the size of the band (two guitars, two drums, bass, keyboards, and background vocalist) suggests. Despite at some points having two keyboardists, the piano usually sounds peripheral to the band, and a listener not paying close attention might think Keith Godchaux had left the stage for long stretches. The rhythm guitar of Bob Weir is also a negligible contribution,. The drummers fall between inspiring and infuriating. The Allman Brothers Band also used two drummers, but the arrangements were more rigid, helping them avoid stepping on each other. The Dead drummers fall in and out of sync with such regularity that it might as well be planned: It is part of their sound. And, if you are a rhythmically challenged suburban kid doing your hippie dance, you can believe you are on beat simply because the amount of drumming offers so many choices. Still, the drumming provides a surprisingly supple foundation for the band to build on; in particular, for bass player Phil Lesh to aid in the liftoff of guitarist Jerry Garcia.

As a bassist, Lesh follows the melody, offering a solid tree trunk of sound out of which Garcia’s solos emerge in torrents of notes as elaborate branches thick with intricate leaves. One could not imagine another band doing better at giving Garcia the solid backing yet incalculable space his guitar needed to shine. If you listen to the Jerry Garcia Band from this period, you will hear this same virtuoso with musicians who are at least as good as the Dead. Yet there is no comparison. With the Jerry Garcia Band the playing is often aimless, unfocused, and unanchored, lacking any drama: like his efforts to make compromised jazz jams out of Motown. Garcia plays well. Everyone plays well. But a large part of the magic of the Grateful Dead was that over years of shows together, this was a band that knew how to perfectly frame its incomparably brilliant soloist, allowing him and them to achieve at a level that his music without them and theirs since his death will never approach.

What was available to the Grateful Dead in May of 1977 was a new ability to weave together these ingredients, mixtures of melody and solo virtuosity, into suites that could run close to 30 minutes without ever wandering into the thicket of experimental and abstract sound that “Dark Star” represented. At the Cornell show, “Scarlet Begonias” into “Fire on The Mountain” (both post-1972 songs) offers 26 minutes packed with creative soloing by Garcia, without ever ceasing to be hummable. This was the Grateful Dead teaching a young audience how to listen to long, instrumental suites by the Grateful Dead. Digest this, then “Dark Star” is a short step away. It is easy to mock the hippy dippy sentiments of the lyrics or to argue the band had backed off from their earlier embrace of true improvisation and experimentalism. And both charges have some truth. But there are no artistic compromises in the playing here. Garcia’s solos have a drama that justifies, explores, pushes against and chimes with the cushion of melody built for him by the band. The sound is consistently exhilarating. On another night included in the newly released box set, this same improvisational high came during the song suite “Terrapin Station.” This is music that is accessible yet still rewards repeated listening.

Rather than be a hit and miss live act, in May 1977, the Grateful Dead discovered they could deliver every night with any part of their entire musical history. They could still please the initiated while they found a more engaging way to present their jams to the newbie. As the world was looking away to dance the hustle, watch Saturday Night Fever. or freak out at the English kids putting safety pins in their cheeks, the Grateful Dead had found a way in these shows to remain sirens to select members of the new generation, calling on them to join the band on their journey. •

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QV-2EJnfzjY

Feature image courtesy of Hypnotica Studios Infinite via Flickr (Creative Commons). Images courtesy of Chris Stone via Flickr (Creative Commons), and Viniciusmc, Northamerica1000, and Grateful Deadhead via Wikimedia Commons.