Despite its outsize influence on American literature, The Smart Set is hardly known today. Yet there was a time when the writing in its pages set the tone for the social and cultural debates of the period. Originally founded in 1900 by Colonel William d’Alton Mann as a magazine for New York’s upper classes, in 1913, under the editorship of Willard Huntington Wright, The Smart Set, which this online arts and culture journal was named for, became a venue for the literary avant-garde. An art critic whose star rose as quickly as it fell, Wright later made his mark as a writer of detective novels under the name S. S. Van Dine. But during his year-long tenure as editor of The Smart Set, he introduced a new level of literary quality that would be maintained by his successor, H. L. Mencken. Still working as a journalist for The Baltimore Sun, Mencken — who had been contributing literary criticism to The Smart Set — teamed up with the magazine’s theater critic, George Jean Nathan, to establish a cultural force unlike any other in the literary landscape of the time.

Mencken and Nathan stepped up to their editorial task with a unique mix of sincerity and irony — a critical approach that was ruthless in its analysis of art and society and uncompromising in its pursuit of a modern social and artistic vision. Featuring voices known and unknown, they critiqued American culture while filling their magazine with examples of stories, poems, essays, plays, and short shorts that they believed embodied the future of the nation. Having inherited a magazine that had, in its thirteen years, published established writers like Ambrose Bierce, Theodore Dreiser, and Jack London, as well as experimental writers like Joseph Conrad, Ford Madox Ford, D.H. Lawrence, and W. B. Yeats, Mencken and Nathan hurled themselves into the thicket of anglophone literary production, publishing well-known writers alongside young talent, and creating a unique mix of old and new, familiar and refreshing, traditional and experimental. They struck a balance that ushered in a new era in American literary production while preserving the cultural heritage in which they believed most profoundly: freedom of the individual and faith in the power of creativity.

Mencken and Nathan breathed their unique brand of meaning-making into the magazine’s very title. What began as The Smart Set for cultural elites — the word “smart” being used in the sense of fashionable or upscale — became a magazine for people who valued what was “smart,” or, in this case, sharp. It was intellectual, but it was not pretentious. This made the magazine relatable to younger audiences searching for meaningful debates and imaginative stories. But it also drew the wrath of the elites who believed intellectuality belonged to the upper classes. In 1920, Charles A. Beard, the American historian and professor at Columbia University used the 300th anniversary of the Mayflower’s landing to take a dig at Mencken. “The Puritan may not measure up to Mencken’s ideal of art,” wrote Beard, “but he did build houses that are pleasing to the eye and comfortable to live in, and he never put his kitchen midden before his front door.” He was right. Comfortable and aesthetically pleasing housing was not the top of Mencken’s idea of what made art meaningful to people in the real world.

Mencken had to take his criticism as nastily as he dished it up. And he rarely helped his own cause. He was documented saying plenty of smug and nasty things about different ethnic and racial groups in newspapers while he was alive, and in diaries that he himself instructed be published after he died. It does not appear that Mencken insisted on being seen as “good” — he was ready for people to know the ugly parts of him too. Perhaps this is why a number of writers and intellectuals, including Ralph Ellison, Norman Mailer, and Arthur Miller all signed an open letter in the New York Review of Books that expressed “dismay at the over-reaction to the Diary of H. L. Mencken.” They continued:

His hyperbole did not foreclose warm friendships with Jewish publishers, writers and doctors; no white editor of the day did more to seek out and encourage black writers; no editor did more to fight for freedom of expression for all Americans. Whatever Mencken’s “prejudices” — the word he himself used to describe his essays — he was a tremendous liberating force in American culture, and should be so celebrated and remembered.

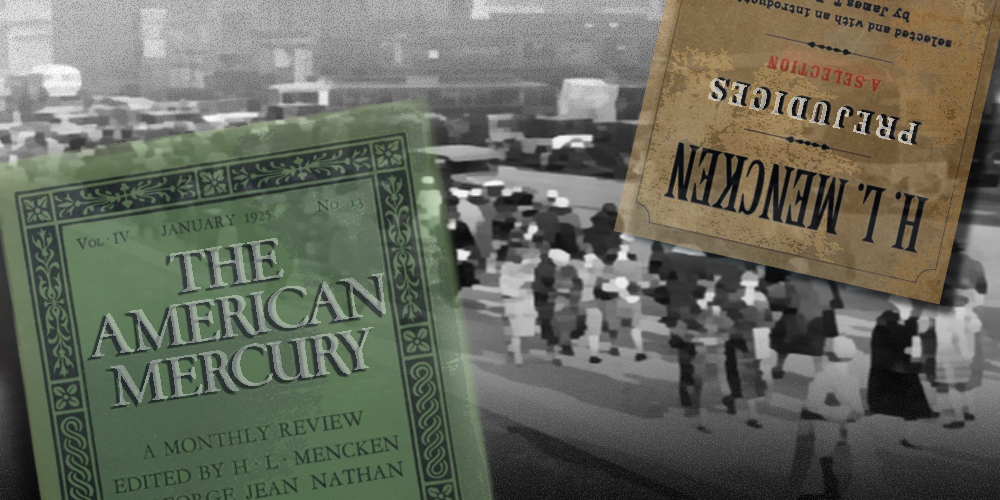

Mencken published six volumes of these Prejudices between 1919 and 1927. And during that time, as co-editor of The Smart Set and The American Mercury, he helped bring an incredible number of writers like these into the broader literary conversation. There is no question that, in his deeds, he was someone who opened up rather than closed down the gates of plurality and diversity. Beard’s implication that Mencken had a habit of putting his “kitchen midden,” his household trash, out for everyone to see was accurate. And it revealed a conservative distaste for Mencken’s open critiques of American literature and society. Mencken, it seemed, was too direct for Beard. He was too straightforward about what he thought was right — and wrong — with the nation.

This ironic sort of brashness, together with their sense of integrity, brought Mencken and Nathan’s tenure as editors of The Smart Set to an abrupt end in 1923. They had written a satirical piece on the interstate funeral procession of President Warren G. Harding, whom they had often critiqued in their pages, but the magazine’s new owner, Eltinge Warner, called it treasonous. This was just one example of the challenges that writers and artists faced during this period of United States history. The Sedition Act of 1918, which had limited free speech, had only been repealed two years earlier, yet the Espionage Act of 1917, which included many similar elements, was still law. And just as the Roaring Twenties were revving up, so was the First Red Scare, which was, in many ways, a dry run for the coming Cold War. The growing links between communism and intellectualism made “smartness” less socially attractive. It no longer seemed socially beneficial to be sharp. Cultural survival preferred what was fashionable.

Mencken and Nathan chose to pursue their vision outside the purview of a publisher who believed that hypocrisy was justified in service of patriotism. They started a new magazine, The American Mercury, published by Alfred A. Knopf, which they co-edited for a decade to much success. But the magazine never quite rivaled the legacy they had created with The Smart Set. Differences between Mencken and Nathan did not help the cause either. Still, in the time they worked together, they had created a model that could be repeated, not just by them, but by others — not least of which were Harold Ross and Jane Grant, who, inspired by The Smart Set, founded The New Yorker.

Cultural critics of the day continued to recall the contribution that the magazine had made to the literary arts. In 1934, Burton Rascoe and Groff Conklin prepared an 840-page anthology of The Smart Set, featuring some of its most significant writing. Reviewing the volume in The New York Times Book Review, Louis Kronenberger wrote: “The Smart Set has become something of a legend. . . . You were very conscious that it was making literary history.” He wrote these words merely ten years after Mencken and Nathan had left the magazine. Yet they made clear that, as editors, the efforts that Mencken and Nathan had expended had been enshrined in what became one of the most influential literary magazines ever published in the United States.

Today, we might say that there’s no magazine — perhaps other than The New Yorker — that can match the combination of prestige and influence that The Smart Set had on American letters. And, as a magazine inspired by The Smart Set, it can even be said that The New Yorker continues its legacy. But the cultural role of the magazine can also be viewed from another perspective. The Smart Set showed what a literary magazine could do in the culture. It proved the potential for the written word not only to influence the debates of the day, but also to raise the standards to which other literary magazines and journals strove. In many ways, The Smart Set was succeeded not by any one magazine, but by the tradition of quality literary publishing as a whole — showing that a publication that was popular could also be good. In this sense, many literary magazines, and not just one, belong to the legacy of The Smart Set, the editorial vision of which proved that you can be critical of your society, and still believe in the greatness of its potential.•