In his essay “Death of the Author,” Roland Barthes tries, in the bookish prose of which academicians are so fond, to persuade us

that a text is . . . a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture. Similar to Bouvard and Pecuchet, those eternal copyists, at once sublime and comic and whose profound ridiculousness indicates precisely the truth of writing, the writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original. His only power is to mix writings, to counter the ones with the others, in such a way as never to rest on any one of them.

Writers are indeed an incestuous little bunch eternally doomed to borrow, copy, steal, plagiarize, allude to, accidentally repeat, consciously imitate, alternately praise and denigrate each other’s work. Originality held aloft by its own purity in some Platonic realm . . . no, it doesn’t exist. But Barthes goes overboard by insisting there’s nothing original in any text. More likely there are varying degrees of originality as well as more or less acceptable ways of allowing the work of one author to surface in the work of another’s. Hence, T.S. Eliot’s famous dictum: “Bad poets borrow; good poets steal.”

Before applying Old Possum’s axiom, it’s probably best to establish what he meant. The actual quote is “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different” (“Phillip Massinger”).

It seems reasonable to interpret this to mean that an author who uses someone else’s work clumsily or obviously has merely borrowed what he could not come up with on his own. If, on the other hand, an author uses the work of another writer so skillfully it is a seamless fit within her own work, so deftly readers either don’t notice or can’t be sure of an earlier source, if she modifies it enough to make it her own within its new context, then she has “stolen,” which, in this case, is an electron carrying a positive charge. In other words, I’m willing to concede to Barthes that there’s no getting away from the work of others in one’s own work, but how that is accomplished makes all the difference.

Saint Augustine, one of antiquity’s best-known authors, addressed the topic in his Confessions. Section [120:] XL:60 is titled: “Whatever has been correctly said by the heathen is to be appropriated by Christians.” It’s followed by “If those who are called philosophers, and especially the Platonists, have said anything that is true and in harmony with the faith, we are not only not to shrink from it but to claim it for our own use from those who have unlawful possession of it.”

In other words, permission to rip off pagan authors granted. Not very saintly but certainly convenient for poets such as Milton, who seems to have taken Augustine at his word. I remember reading the opening books of Paradise Lost as a freshman at Rutgers University and being stunned, rather like a clubbed fish, by the language, the baroque imagery, even the syntax.

Millions of Spirits for his fault amerc’t

Of Heav’n, and from Eternal Splendors flung

immediately comes to mind. Putting flung at the end of the second line seemed to me the lexical equivalent of a painting whose image isn’t fully contained by the canvas. If we imagine the artist’s subject to be a plummeting angel, maybe we can see a divine ankle, but the foot disappears over a border; maybe one celestial wing is in full view, but of the other a full frantic third is flapping somewhere beyond the frame. It seemed to me there was biblical authority in Milton’s words, a preternatural brilliance in his verse.

Like every other freshman literature major, I fell headlong for Satan — particularly his defiance even in defeat, resoundingly summed up by Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. What could Camus add to the archetype of the rebel that wasn’t already here? It wasn’t until I re-read Homer’s Odyssey some years later that I was struck by an irrefutable parallel to a verbal rebuff from Achilles to the wily Odysseus. When Odysseus runs into his celebrated compatriot in the underworld, he says, “Achilles . . . honored as though you were a god . . . and now you are a mighty prince among the dead. For you . . . Death should have lost its sting” (Odyssey 11.480). (This last bit, of course, was later to be — if not thieved — certainly referenced by John Donne in his best known poem, “Death Be Not Proud,” which of course ends with “Oh Death, where is thy sting?”) Achilles replies, “I would rather serve as the slave of another than be lord over the dead.”

There’s no question of Milton’s having read the Odyssey (as well as every other classic in print); the opening lines of Paradise Lost were composed in conscious imitation of the Classical epic and recall both the Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid. But I don’t take issue with Milton for appropriating one of Achilles’s great lines because he did in fact steal it. The meaning of I would rather serve as the slave of another than be lord over the dead has been reversed to fit Milton’s tragic hero. It’s not an allusion to Achilles, who’s bemoaning his fate; it’s a war cry to rally Satan’s fallen comrades-in-arms. In the context of the Christian hell, it is as inspiring as Achilles’s line is sobering. It is theme and variation without music other than the meter of the poems involved, almost as if Milton’s epic were updating Homer’s, as if the English Puritan were bantering with the Greek pagan. Milton has enlarged literature, not diminished it.

Tracking down the roots of various literary lines isn’t exactly Richard Burton on his quest to find the source of the Nile; it’s more a solitary parlor game, a pastime, somewhat more involved than a crossword puzzle.

The game asked to be played again when I picked up a copy of Amin Maalouf’s Leo the African. Maalouf is a Lebanese author fond of writing about historical figures such as Omar Khayyam, Mani (the founder of Manichaeism), and Hasan al-Wazzan, a.k.a. Leo the African.

The passage in question concerns a minor character in his 16th-century tale:

Gaudy Sarah came knocking at our door. Her lips were stained with walnut root, her eyes dripping with kohl, her fingernails steeped in henna, and she was enveloped from head to toe in a riot of ancient crumpled silks which breathed sweet-smelling perfumes. She used to come to see me — may God have mercy upon her, wherever she may be! — to sell amulets, bracelets, perfumes made from lemon, ambergris, jasmine and water lilies, and to tell fortunes. She immediately noticed my reddened eyes, and without me having to tell her the cause of my misery began to read my palm like the crumpled page of an open book.

Without lifting her eyes she said these words, which I remember to this day: “For us, the women of Granada, freedom is a deceitful form of bondage, and slavery a subtle form of freedom.” Then, saying no more, she took out a tiny greenish stoppered bottle from her wicker basket. “Tonight you must pour three drops of this elixir into a glass of orgeat syrup, and offer it to your cousin with your own hand. He will come to you like a butterfly toward the light. Do it after three nights, and again after seven.”

Although I’d never read the novel before, I knew this character. Then I realized I’d met her in My Name is Red by Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk. I dug out my copy of My Name is Red (and I do mean dug: a resident of Istanbul for seven years, I have some clothes, scattered memorabilia, and about 1,000 books with which I simply cannot part crammed into what amounts to a climate-controlled garage here in the States.) Pamuk’s character, a denizen of 16th-century Istanbul, describes herself this way:

When I load my wares — items cheap and precious alike, certain to lure the ladies, rings, earrings, necklaces and baubles — into the folds of silk handkerchiefs, gloves, sheets and the colorful shirt cloth sent over in Portuguese ships, when I shoulder that bundle, Esther’s a ladle and Istanbul’s a kettle and there’s nary a street that I don’t visit. There isn’t a word of gossip or letter that I haven’t carried from one door to the next, and I’ve played matchmaker to half the maidens of Istanbul, but I didn’t begin this recital to brag.

Black, one of the other characters in the novel, offers this impression:

As soon as we entered the street, I was about to swiftly mount my steed and disappear down the narrow way like a fabled horseman, never to return again, when an enormous woman, a Jewess dressed all in pink and carrying a bundle, appeared out of nowhere and accosted me. She was as large and wide as an armoire. Yet she was boisterous, lively and even coquettish.

[ . . . ]

Her body lengthened like the slender form of an acrobat and she leaned toward me with an elegant gesture. At the same time, with the skill of a magician who plucks objects out of thin air, she caused a letter to appear in her hand.

The skeptic will ask, quite rightly, how I can be so sure it’s not simply coincidence. I can’t of course, but My Name is Red is not Pamuk’s first attempt at historical fiction. In 1983 he published The White Castle, a book that I found so lacking in the details required to make me believe I was in 17th-century Istanbul, I put it down after 50 or so pages. This is decidedly not the case in My Name is Red, which is rich in descriptions of Istanbul and even richer (to the point of making one’s stomach queasy as from the consumption of a whole tray of syrup-drenched pastries) in descriptions of Persian miniaturist paintings.

Pamuk seems this time to have taken great pains to bring a bygone Istanbul to life. Neighborhoods are reconstructed in all their Ottoman splendor — or squalor as the case may be. Since it’s common enough practice when writing historical fiction to read other historical novels, and since Maalouf is immensely popular in Turkey, it’s virtually impossible that Pamuk is unaware of Maalouf’s work. We have both motive and opportunity. And who better to learn from than a successful Middle Eastern author of historical fiction?

Beyond that, there are too many points of correspondence that I find too similar to be mere chance. Sarah is go-between for a woman named Salma and her cousin Muhammad. Esther is go-between for Black and a woman named Shekure. Both Sarah and Esther are Jewish. Both inhabit 16th-century, Muslim cities. Both are gossip-mongers (“One day,” Maalouf writes on page 28 of his novel, “Sarah arrived, her eyes full of news. Even before she could sit down, she began to tell her stories with a thousand gestures.”). Both perform the same plot function: facilitate intrigue. Their personalities, which leap from the dialogue, their exaggerated body language, the air of drama that surrounds both, are almost indistinguishable. Pamuk has basically recycled Maalouf’s character, but then Gaudy Sarah is a picturesque device for advancing a plot — who can blame him?

Years before I’d ever heard of Pamuk or Maalouf, I realized that Moby-Dick is a treasure trove of pilfered texts. Ishmael’s profound and resonant “So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense,” for example, probably has its roots in Socrates’s “Madness coming from God is superior to sanity of human origin”. And then there’s chapter 37 (“Sunset”), in which Ahab’s monologue sounds oddly familiar:

Oh! time was, when as the sunrise nobly spurred me, so the sunset soothed. No more. This lovely light, it lights not me; all loveliness is anguish to me, since I can ne’er enjoy. Gifted with the high perception, I lack the low, enjoying power; damned, most subtly and most malignantly! damned in the midst of Paradise! Good night — good night!

Compare this with Hamlet’s speech in Act 2, scene ii: . . . this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air — look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire — why it appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors.

Even the ending of Ahab’s soliloquy recalls Horatio’s farewell at the end of the play: Good night, sweet prince.

Ahab, however, resembles Milton’s Satan much more closely than he does Hamlet. Indeed, it’s not an accident that Ahab is “damned in the midst of Paradise”; so was Satan. Moby-Dick is in many ways Paradise Lost with Ahab recast as the fallen archangel. (I would argue that there’s some of Hamlet in Milton’s Satan as well, particularly his speech in Book 9:

. . . With what delight could I have walkt thee round, / If I could joy in aught, sweet interchange / Of Hill, and Vallie, Rivers, Woods and Plaines, / Now Land, now Sea, and Shores with Forrest crownd . . . but I in none of these / Find place or refuge; and the more I see / Pleasures about me, so much more I feel/Torment within me, as from the hateful siege / Of contraries; all good to me becomes Bane . . . )

From Ahab’s odd scar, which Melville compares to “that perpendicular seam” made when “lightning tearingly darts down a tree,” which is a conscious allusion to the “Deep scars of thunder that had intrencht” Satan’s face to the novel’s penultimate sentence: “ . . . and so the bird of heaven, with archangelic shrieks, and his imperial beak thrust upwards, and his whole captive form folded in the flag of Ahab, went down with his ship, which, like Satan, would not sink to hell till she had dragged a living part of heaven along with her . . .” it’s clear Melville wrote Moby-Dick with Paradise Lost in mind.

Since this isn’t the first time the two have been compared, there’s no need to go into any depth. The point is that the clues here are deliberate — Melville is making an effort to link his novel to Milton’s poem. He’s building on the earlier work, in a sense incorporating it into his own, and he wants us to feel the kinship between his work and Milton’s.

Which brings us to the next round of this parlor game. It began innocently enough when a fellow American émigré in Istanbul asked me to critique a paper he was presenting on McCarthy’s The Road. I’d never read it, so I picked up a copy and, surprisingly enough, thought I saw a glimpse of the apocalyptic world in Lucifer’s Hammer, ’70s sci-fi in which a comet strikes the Earth and wipes out civilization as we know it. Humankind divides into two camps: the cannibals and “the good guys.” The division is identical in The Road. But from what I can recall (I read Lucifer’s Hammer a couple of decades ago), McCarthy owes decidedly less to co-authors Jerry Pournelle and Larry Niven — assuming he ever even came across a copy of Lucifer’s Hammer — than Shakespeare does to Prince Amleth.

A quick digression: Hamlet was originally a Norse legend — all plot and action, not much pith — and outside of academia no one really remembers it. At least in this country. Amleth, one transposed letter away from Hamlet, means “imbecile” or “foolish” in a Danish form of Icelandic, and, like Hamlet, Amleth fools the king by feigning insanity. A page-turner (so to speak) when it was finally committed to print in the 13th century, it had the usual plot connivances (the cunning Amleth kills quite a few more people and lives longer than Hamlet) but would have been forgotten more completely were it not for Shakespeare’s re-telling. The Bard stole a night of fireside entertainment and turned it into a world classic.

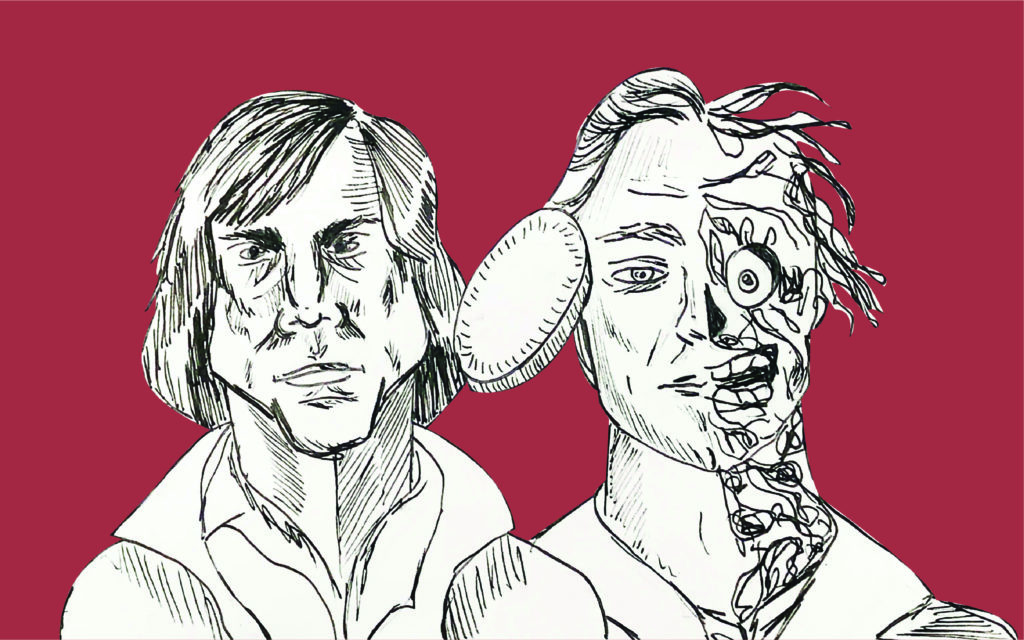

Back to the present day and another McCarthy novel — No Country for Old Men. Anton Chigurh, “a true and living prophet of destruction,” is the book’s remorseless, coin-tossing villain. The Web picked up pretty quickly on another chance-obsessed, coin-wielding psycho (Harvey Dent, a.k.a. Two-Face, from the Batman series) but buzzed mostly about the film versions of these iconic bad guys and didn’t see much in common between them other than the loose change they keep handy.

Two-Face makes his first appearance in Detective Comics #66, written by Bill Finger and illustrated by Bob Kane. The issue was released in August of 1942 by DC comics. I imagine nine-year-old Cormac McCarthy sprawled on the floor, absorbed in the dark tale. Years later, the comic book winds up crammed into a box in the garage with lots of other magazines, and Two-Face lies forgotten under a coil of garden hose. 1995 rolls around. Batman Forever — easily the worst of the Batman movies — is released. McCarthy doesn’t bother to see it, but maybe, after it’s made its rounds in theaters and shows up on tv, he’s channel flipping and catches Tommy Lee Jones doing his version of Two-Face. “One man is born a hero, his brother a coward,” Jones rants. “Babies starve, politicians grow fat . . . holy men are martyred, and junkies grow legion. Why? Why, why, why, why, why? Luck!” he concludes. “Blind, stupid, simple, doo-dah, clueless luck! The random toss is the only true justice.” (Jones, of course, would later show up in the Coen brothers’ adaptation of No Country for Old Men.) McCarthy, with his affinity for the biblical, probably enjoyed the mention of holy men, and he makes explicit reference to controlled substances in No Country for Old Men: “I think if you were Satan and you were setting around tryin’ to think up something that would just bring the human race to its knees what you would probably come up with is narcotics,” says Sheriff Ed Tom Bell. Probably more tantalizing to McCarthy, though, would be the hint that the coin toss invites the cosmos to participate in human affairs.

I envision McCarthy walking into the garage or the attic and digging out his old comic book collection. Pulling open the box flaps releases the mildewy smell of nostalgia. He re-reads Detective Comics #66, and there’s Two-Face, disfigured after a gangster named Moroni throws acid on him. “I’m not a man!” Two-Face shouts. “I’m half a man . . . beauty and beast! Good and evil. I’m a living Jekyll and Hyde.”

What really connects Chigurh and Two-Face isn’t the mere act of flipping a silver piece, but rather the way they divorce themselves from their actions — and guilt — by identifying themselves with Newtonian mechanics; they are simply agents of a natural law, and it is the universe and individual choice, not Chigurh or Two-Face, that bring someone before their judgment. Chigurh implies this when he has Carson Wells, a fellow hired gun, at his mercy. “If the rule you followed brought you to this,” he asks, “of what use was the rule?”. He relies on a simple cause-effect relationship, assumes that Wells blindly follows “rules” the same way he does, and takes no responsibility for the fact he’s about to kill Wells (who, admittedly, would have done the same to Chigurh had the situation been reversed). Wells himself is aware of the peculiar spin to the cogs in Chigur’s head. Earlier in the novel, he described Chigurh as a man with “principles. Principles that transcend money or drugs or anything like that.”

Unlike Two-Face, Chigurh doesn’t need to come up with a coin every time he wants to make an important decision or pull the trigger. Most of the time he knows exactly who he is going to kill although, again, his victims are at fault; they have made the decisions that led to the predicament they are in. The first time he pulls out a coin, he uses it to decide whether or not a store owner who has irritated him deserves a death sentence. The clueless fellow wins the toss, the quarter, and his life. The second time Chigurh pulls out change, it’s to decide whether or not to execute Carla Jean, whose husband, Llewellyn, is already dead. Chigurh is making good on a threat to Llewellyn to kill his wife, but she pleads enough for Chigurh to give her a gambler’s chance. She misguesses but sees clearly enough what’s going on: “You try to make it like it was the coin. But you’re the one.” Like Two-Face, one of Chigurh’s principles is to abide by the outcome of the coin toss however he might feel about it. “It could have gone either way,” he answers.

Possibly, the coin-flipping in which Chigurh and Two-Face engage, as well as the attendant philosophy — removing the human factor from the fate-deciding equation — is mere coincidence. A variation on coin-tossing appears in All the Pretty Horses, an earlier novel. On pages 230-31 of the paperback, McCarthy goes all the way back to the mint where the coin was struck: the fate being decided is in the hands of the guy who puts the slug into the machine in one of two ways although the mechanism by which this decides a human fate is never explained.

There’s a good chance young Cormac McCarthy never read Batman comics or saw the Dark Knight movies. There’s an equally good chance McCarthy pulled the eccentric Anton Chigurh out of the tarry pit of his own psyche. The same can’t be said of Two-Face. Finger and Kane were open about the original template for their villain: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Nonetheless, I think it’s fair to say that what began as blatant borrowing for the Batman series evolved into something more (in later appearances, Two-Face’s belt buckle is a Yin/Yang symbol), something quite distant from Two-Face’s Victorian inspiration, something even Roland Barthes could have had fun with. •