All The Way, HBO’s new movie about the passage and aftermath of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, is a messy and curiously double-minded affair. Like Selma, it wants to show that the shopworn narrative of white men grappling with fate in smoky rooms was never the whole story. But All The Way doesn’t give Martin Luther King’s movement enough screen time to live again as the complex entity it was. Instead it’s portrayed as one of the many blocks Johnson has to shift around to secure passage of the bill.

But if All the Way reduces itself to the story of Johnson’s break with Southern whites then, however unintentionally, it does succeed in making one point very clearly: Nostalgia for the Johnson presidency is misplaced, thanks to forces set in motion by the man himself.

Obama’s second term has been rife with this species of nostalgia, which began with two precipitous events: the publication of the long-awaited fourth volume of Robert Caro’s biography of Johnson, and the dawning realization that if Barack Obama was elected to a second term the Republicans in Congress would block every single initiative he put before them. Historical comparisons are catnip to Washington’s paid thinkers, and a cottage industry of Johnson think-pieces bloomed. The less astute columnists built specious musings out of anecdotal accounts of disaffection between Obama and Congress. They wondered if the President was too remote or too partisan. “Washington is thick with stories about Obama’s insularity and distance,” wrote Richard Cohen, who fumed because “Obama cannot or will not indulge in the sort of face-to-face politicking that Johnson so favored.” What we needed, these pundits reasoned, was a president who could sweet-talk and brow-beat the Senate into moving mountains. But it would have been more accurate to blame Johnson than to praise him: As Robert Caro himself said at the time, Barack Obama is Lyndon Johnson’s legacy. Caro was referring to the man himself, but the statement is just as true if you apply it to the era.

The Civil Rights Act was languishing in Senatorial purgatory when Johnson took office. As Majority Leader, Johnson shepherded a civil rights bill to passage in 1957, but it had been watered down to near-meaninglessness. This time, he told Richard Goodwin, “I’m not going to bend an inch. In the Senate I did the best I could. But I had to be careful . . . But I always vowed that if I ever had the power I’d make sure every Negro had the same chance as every white man. Now I have it. And I’m going to use it.” Spurred on by the civil rights movement, harnessing its energy, he outflanked the South and secured the bill’s passage with an alliance of Republicans and liberal Democrats.

And then the South began drifting out of the Democratic party. Johnson fended off a nomination challenge from the segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, weathered a walkout by some Southern delegates at the convention, and lost only six of 50 states to Republican Barry Goldwater in the general. Excepting Goldwater’s home state of Arizona, they were all in the South. This paved the way for Nixon’s “southern strategy” in 1968, with its barely-concealed racial overtones. Much of the region went for Wallace’s third-party run in 1968, but it was coming into the fold — Nixon won it all in 1972.

The American political system was undergoing a drastic realignment. Short of reversing his position on civil rights and the welfare state, there was nothing Johnson could have done to change it. Indeed, he hastened it. His most fateful decision was the massive escalation of war in Vietnam. By the end of his presidency, the United States had half a million troops in the field, who pulverized the Viet Cong but could not defeat them. Johnson was so unpopular he decided to drop out of the race in 1968 after a single primary. To many whites at the time, accustomed to domestic tranquility and the subservient quietude of the nation’s minorities, America seemed on the verge of chaos, its colleges and cities plagued by a miasma of riots and protests over Vietnam, women’s rights, civil rights, immigration, and the iniquities of capitalism. The Johnson era produced a flurry of legislation in response, but acrimony reigned.

Nixon was astute enough to mark the shifting wind. His “law and order” campaign (read: things will be the way they were before) won in a landslide, and America’s political landscape lurched toward its modern configuration: The Democrats were becoming more urban, less white, and less Southern.

Republicans headed in the opposite direction. The rise of evangelicals as an organized political force can also be dated to the Johnson era. Contrary to received wisdom, evangelical leaders were galvanized not by abortion or “family values,” but by the federal government’s efforts to impose desegregation on private, whites-only schools. In 1980, Ronald Reagan wove all of these themes together, packaged with his trademark sanguinity. 20 years later, George W. Bush ran on a subtler, duller version of the same playbook.

By the time Barack Obama took office in 2009, the political realignment that Johnson began had hardened in ways not immediately obvious — the new President was greeted with a wave of misplaced optimism. Obama was able to pass a landmark healthcare bill and ward off the worst effects of the Great Recession, but his window of opportunity was perilously brief. The Republicans were superior organizers, and they had parlayed the changing political landscape into decisive victories at the state level, gerrymandering districts across the country. This fostered more extreme candidates and increased party discipline: Significant legislation now had to pass with a filibuster-proof majority of 60, which is simply not possible against a party as homogeneous as the Republicans are today. There were no more moderates for Obama to peel off, as Johnson once did. Obama seems aware of the comparison. “My first two years in office,” he told Vox’s Ezra Klein last year, “when I had a Democratic majority and Democratic House and Democratic Senate, we were as productive as any time since Lyndon Johnson. And when the majority went away, stuff got blocked.”

But there are two qualities of Johnson had that Obama lacked, and that has made it harder for him. The first is knowledge of the his political opponents. Johnson spent over 20 years in Congress, six as Majority Leader in the Senate. He knew the South well – he’d voted with it against civil rights for decades – so when he turned around and endorsed civil rights, he understood the people he had to beat. “He’ll pass them,” his former friend and mentor Richard Russell said, “whereas Kennedy could never have passed them.” Congress is far less pliant today, when the threat of a filibuster looms ominously over every bill. Obama’s mistake, pace his critics, wasn’t in neglecting the backslapping, deal-making aspect of the Presidency, but in taking too long to realize how sclerotic Congress had become. He was too pliant, and because of that he gave up more than he should have.

The other quality of Johnson’s which Obama lacks is whiteness, and that has hurt him far more than anything else. America had become less white and more socially tolerant, and Obama’s skin was and is a potent symbol of that change. In response, a toxic admixture of ethnic and economic anxiety produced a state of perpetual panic on the right. These are massive demographic and macro-economic forces over which a president has almost no control, and so there is little sense looking back with nostalgia to a more productive time, or a more productive President. The paralysis of the Obama era is an unavoidable legacy of the changes wrought during the Johnson era, changes that All The Way so effectively conjures to life.•

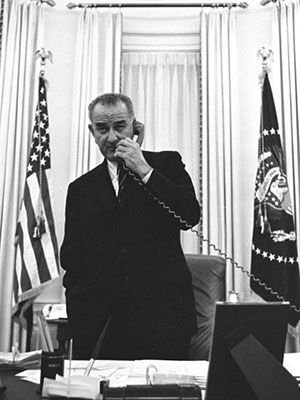

Feature image courtesy of Jerchel via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).