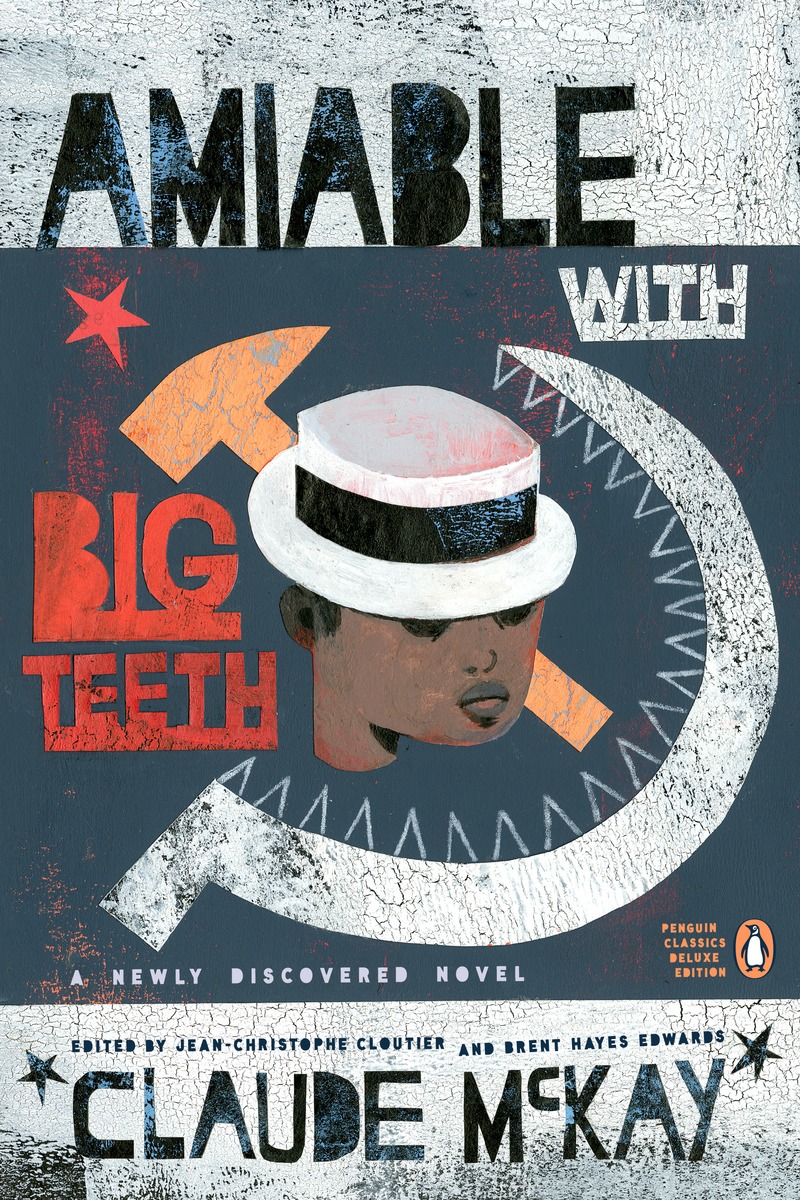

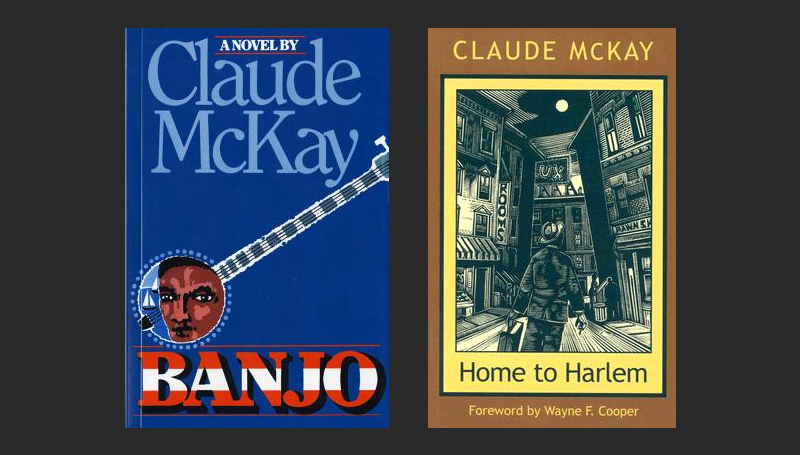

Every literary season deserves at least one unexpected pleasure. For the fall of 2016, this pleasure appeared with the discovery and publication of a long-lost novel by Claude McKay. Known as the “rebel sojourner” of the Harlem Renaissance, McKay enjoys more than his fair share of supporters and detractors. His sense of rebellion persisted throughout his unsettled life, as compulsive and widespread as his travels. The newly discovered novel, with the suitably prickly title of Amiable With Big Teeth, won’t likely alter or settle McKay’s reputation conclusively, but it will complicate it, and in a good sense. Most striking, perhaps, is that the book has a deft plot, rather unlike his earlier narratives (recall that Banjo is subtitled A Story Without a Plot). Some issues and concerns recur from the previous fictions, but they often appear to be over-shadowed by the political questions of race and color. Amiable certainly continues in that vein, but adds to it a smoother sense of conflict and development, complete with revelatory surprises and a range of tonal situations, from romantic innocence to farce to grim burlesque.

What chiefly sets Amiable off distinctively from other McKay novels is the presence of full-throated political disputes, most of which were burning heatedly in the 1930s, during the rise of fascism. Home to Harlem and Banjo, written in the late 1920s, both made room for politics, and in both places, the character of Ray served as McKay’s spokesperson and main political theorizer. But in Amiable, no character commands center stage, which means McKay can show everyone’s political views in all their complexity. But such complexity can also be read as a form of universal rejection. Many readers of this “new” novel will catch more than a whiff of McKay’s cynicism, if not a quiet nihilism. The entire novel is set in New York, and the bulk of it takes place in Harlem. But the date is 1937, so the Renaissance has begun to fade, and the Harlem riot of 1935 is also only lightly mentioned, and though some Depression culture appears, it registers only as a thin, indefinite shadow. But leftist revolution and anti-colonialism dominated the main questions of the day.

What strikes home, and stands as the novel’s main underpinning, is the emphasis on the problems of group identity and the international range of revolutionary sentiments. All of this thematic and emotional material arises from the first pages as what we might call “the problem of Ethiopia.” A war is taking place overseas between Italo-Fascist forces and a near-mythical model of liberation in the form of the North African state of Ethiopia. Led by Emperor Haile Selassie, the country has been called the most mysterious and misunderstood political nation in the 20th century. For many readers there persists the memory of Mussolini’s savage suppression of Ethiopians, woefully under-equipped and the helpless victims of aerial bombardment. The Harlem community of African Americans (McKay refers to them as Aframericans) turned to this small, underdeveloped country to support it against fascism and hold it up as a symbol of anti-colonialism and national liberation.

As a novelist, McKay was vividly political. One commentator on Banjo, his picaresque story of dockside workers, pointed to its sailors in Marseilles as emulating a form of “oppositional primitivism,” that is, a rejection of the values of industrial capitalism by contrasting it with group solidarity and an embrace of personal freedom, if not license. Though Amiable is thick with political values of all kinds, McKay invokes only a little of the vast tangle of primitivist culture (until late in the book, more of which below), and to speak bluntly, he offers no overriding solution, or even a weak resolution, to the tangle of political stances and emotions that drive the story. Something like a deeply rooted sense of unfettered nature and camaraderie is on offer and, with luck, it might prevail against wage slavery and a repressive social order. Still, McKay captures some of the rhetorical temperatures of radical leftist politics, in what W. H. Auden called the “low dishonest decade” of the 1930s, and shows us more of the problem than of any solution.

McKay gives each viewpoint a full hearing, and his outsider status — based on his birth in Jamaica, his coming late to the Renaissance because of his exilic imagination, and his feeling that American blacks sometimes treated him with condescension — resounds here and throughout all of his writings. If we insist on some label, perhaps we could settle on “radical individualist, with a broken socialist heart.” (Alain Locke, accurately but unfairly, accused him of “spiritual truancy.”) Amiable, however, at once presents his outsider dimension with a new brighter glow, but not, as they say, unmixed with heat. McKay utilized the strength of his mentors, forming several solid friendships with some of his fellow writers, but when it came to foursquare social and political questions and affiliations, he was a scold and he held his often-solitary opinions fiercely. This novel clarifies the sources of his many disaffections, using the dyspeptic genre of the satirical novel of manners.

The long arc of Amiable’s plot involves the rivalry between two groups, the Hands to Ethiopia and the Friends of Ethiopia. (The latter group is sometimes called the White Friends of Ethiopia.) Both groups are involved in fundraising to help finance the Ethiopian army, led by Emperor Haile Selassie, in their fight against the invasion by the fascist government in Italy, led by Mussolini. The first pages describe a volatile public meeting meant to introduce a spokesperson for the Ethiopians, a supposed prince by the name of Lij Tekla Alamaya. The rivalry to garner Alamaya’s prestigious support grows immediately complicated as both the Hands and the Friends have distinct and disputatious desires and cryptic allegiances. The Hands are led by Pablo Peioxta, whose modest fortune and bourgeois taste were won by mounting a numbers racket in Harlem, though by now Peioxta has gained a veneer of respectability. His fellow member of the Hands is Dorsey Flagg, a combative type who mistrusts the machinations of the Stalinists. As for the Friends, their leader is the mysterious Maxim Tasan, the most villainous person in the novel. He is aided by a helper named Newton Castle, a clever two-faced manipulator who mistrusts the credulity of the masses. Tasan and Castle are indeed supporters of Stalin, almost to the point of being stooges. The rivalry between Flagg and Castle, the Executive Member and the Secretary, respectively, of the Hands, serves as a counterpoint to the competition between the two groups. Both groups, however, are staunchly anti-Fascist, at least in their public faces. But as the old-line Trotskyists used to say, it is all splits and fusions.

All this combines to produce a novel in which most everyone appears a knave or a fool, as we watch members of each of the two groups engage in the plot’s twists and surprises as well as in its daily Harlemite flavor.

The main preoccupation of the novel is shaped by the congeries of arguments, pettiness, and duplicity between the various political causes and groups. These include Stalinists (plotting to build their control over the Popular Front); Trotskyites (trying to prove that Stalin is evil); black Harlem’s elite (often accused of toadying to whites); white visitors to Harlem (frequently baffled by, or mistrusting, what they see); and assorted organizers and money seekers (whose commitments lag considerably behind their self-aggrandizement). There is tension here of a special kind, however. A sentiment shared by many blacks, and close to McKay’s heart, is the feeling that time, money, and energy might be better spent on raising the salaries of people (as Langston Hughes said about the Renaissance) rather than on distant, high-minded causes. The bitterness of McKay’s sense of alienation was always short-circuited by his unfailing anti-racism, the kind that the novelist meant in everyday life, every day. It functioned as the core of his political imagination and ethos. Virtually every character and complication gets plotted on a graph of racist feelings, from Peioxta’s assimilationism, to Tasan’s opportunism, to the desire of Seraphine, Peioxta’s daughter, to move downtown to a freer life and her mother’s desire for respectability.

The story’s main complication occurs with the discovery that Haile Selassie has been forced into exile by the Italian fascists and thus has abandoned his role as spokesman for the oppressed blacks in Africa and across the globe. This totally unexpected development turns everything upside down. The leader of the Friends, Tasan, is largely unfazed by the exile of Selassie and sees it only as a chance to further gather and strengthen the support of stooges from the Popular Front. As for Peioxta, he celebrates the uncovering of Tasan’s intensely Stalinist bad faith, and does what he can to comfort Alamaya, who has won the affection of Gloria Kendell, a secretary in the office of the Hands. She is chosen to accompany Alamaya on his cross-country lecture and fundraising tour, and their impulsive romance helps him survive the crisis of the Emperor’s forced exile. His political neutrality and his good-natured pragmatism are revealed as his best features.

This political neutrality dominates Seraphine’s outlook and makes her rebellious against her parents. She’s beautiful, naïve, socially ambitious, and eager to marry a prince. However, Alamaya chooses Gloria Kendell instead, even though he discovers that she has gone on stage to imitate an Ethiopian princess, a clearly fraudulent counterpart to fundraising by whatever scheme works. There is also a clever plot contrivance whereby Alamaya thinks he’s lost the diplomatic letter, complete with the Emperor’s seal, that will demonstrate his official standing as Selassie’s envoy. In fact, Maxim Tasan has stolen the letter from him in order to discredit him and hobble the money-raising by the Hands. In turn, the letter is uncovered by Seraphine, which ought to make life a bit easier for Alamaya by restoring his legitimacy. All this takes place while most of the women in the novel — Seraphine and her mother, Gloria Kendell, working as a clerk for the Hands and Seraphine’s friend and roommate, Bunchetta — deal with domestic issues and affairs of the heart. The tone never descends into that of a soap opera, and it serves to offer a contrast to the political discussions, which sometimes read like harangues. To McKay’s credit, the plot and structure of the novel stand as leagues ahead of those in Home to Harlem and Banjo. His artistry impresses even more when we realize the weight of his chronic illness during the time he was working on the novel.

McKay introduces some minor characters throughout, almost as if he were trying to use the complications of novelistic devices to give the novel breathing space, lest the politics overwhelm its interest. But there are two men who have rather sizeable roles in the book, coming into the scene in Chapters 20 and 23, very near the end of the story. Chapter 20 introduces a painter called DèDé, whose gallery opening takes up the whole chapter, and could be a stand-alone satire about the art world. This material is probably based on McKay’s work in the FWP, the Federal Writers’ Project, which absorbed much of his time and his frustration in the last years of his life. It seems as if McKay needed to satirize each cultural group active in Harlem. The events with DèDé and his crowd don’t get fully integrated into the novel, nor, in the final chapter, number 23, does the introduction of a mysterious shaman-like character named Diup Wuluff. Diup makes use of full-size leopard skins in an African style ritual that is cryptically performed to serve as the climax of the novel. Diup is invited to a farewell party planned by and for Tasan himself, and Tasan inveigles the shaman into a wild and implausible scheme. The ending of the party forms the gruesome climax of the novel, but I wouldn’t want to ruin the shock by spelling it out. Suffice to say, McKay has never been more over the top. We have, at the closing moment, left the political disputes behind.

The discovery of Amiable will not likely deepen McKay’s reputation widely and quickly. He never attained the folk-based affection afforded Langston Hughes, though Home to Harlem vied with N—– Heaven as the period’s most shocking black novel. His membership, so to speak, in the Renaissance was always based on underfunded dues. But what he offered remains strong and distinctive, a large body of work made through toil and persistence. Amiable won’t readily be seen as a crowning glory of craftsmanship. But it extends McKay’s historic and thematic reach, which makes his last decade considerably brighter. Darryl Pinckney summarizes McKay’s career, mixing hope and clarity:

McKay’s reputation may have declined in his lifetime, but the worth he found in the culture of the black masses had an immediate influence on a generation of Harlem writers . . . and few black writers have so dramatically embodied the problem of identity, the matter of standing between two worlds, removed and distant from one, yet not completely belonging and then compelled to not want to belong to the other.

This reads like a special adaptation of Du Bois’s famous passage about the black consciousness as it confronts its own twoness. But divided consciousness can serve as a mark of modernism as well as of black experience. McKay’s fiction recalls, at different points, some of the brittleness of Wallace Thurman’s Infants of the Spring or the grating satire of Wyndham Lewis. In turn this can foster the sense that McKay is beyond national identity, a true internationalist. It may be one of those ironies that writers howl at, in painful self-recognition, when we remember that McKay travelled everywhere, yet he could never quite come home to Harlem, even though he remains one of its indispensable lights.

Yet the coda of McKay’s work and its afterlife offered little of the bright lights of fame that some of the Renaissance writers would enjoy, though some had it only posthumously. Again, Pinckney sums up:

Weary of the poverty of his European exile, McKay . . . returned to the United States in 1934, where he was met by a changed market for book publishers and a Harlem hostile to his independence of it. He lived at the YMCA, considered going on relief, endured a stint in a labor camp that was little more than a sanatorium for casualties of the Depression. His autobiography, published in 1937, was also a failure and he managed to offend just about everyone mentioned in it.

Some have suggested that, because of his sense of hopelessness, McKay belongs more to the Lost Generation than to the Negro Renaissance. It serves as McKay’s singular honor that he belongs to both of these literary periods. But also equally striking is that neither period can completely contain the force of his vision. •

Editorial Note: Jean-Christophe Cloutier, a graduate student working with Brent Hayes Edwards at Columbia University, discovered the novel in an archive. The two men have done an excellent job editing and introducing the novel, as well as explaining the circumstances of its appearance.

Feature image and article images by Shannon Sands; source images courtesy of George Dance and laT aurora via Wikimedia Commons. Book covers courtesy of the publishers. Photograph of the Harlem YMCA courtesy of Beyond My Ken via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).