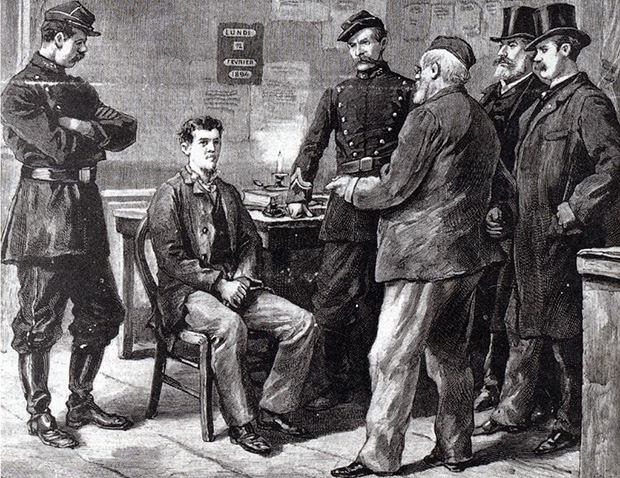

Late one evening in Paris, a young man was scouring the elegant cafes and bistros of the Avenue de l’Opera. He settled on the Cafe Terminus. It was a February night, the 12th to be exact, and the man in question was a bearded 21-year-old student who was dressed in an overcoat and tie. Upon entering the cafe, he ordered two beers and a cigar and sat down. The orchestra began playing 30 minutes later, and the Cafe Terminus soon filled with some 350 people. At 9:01 pm, as the orchestra commenced the fifth piece, the man rose from his table, went to the door, and from under his overcoat he produced a bomb. Lighting the fuse with the cigar he had just purchased, he threw the explosive into the crowded cafe. Within seconds, an eruption rocked the room, shattering the windows and charring the tables. 20 bodies lay wounded amid the acrid odor of smoke and blood. One person was dead. This act of indiscriminate terror, so familiar to us now, took place not in 2014 but 1894, and its perpetrator, whose name was Emile Henry, was not an Islamist but an anarchist.

The first 16 years of the 21st century have been dominated by a single, all-encompassing movement and ideology called radical jihadism. Almost no country, Western or Muslim, has been spared the violence this movement has sparked: New York, London, Paris, Brussels, Istanbul, Baghdad, Jerusalem, Raqqa, Lahore, Dhaka, New Delhi — the cities targeted span the world, making the victims a democratic cohort from every race and religion. Though statistics tell us that there has never been a more peaceful time in human history to be alive, living in a city shortly after it has been attacked will instantly reveal how shallow these numbers are, how real the fear and trembling is. I myself recently felt what I can only call an existential insecurity while walking down the storied Istiklal Avenue in Istanbul two days after an ISIS bombing killed two Americans, an Israeli, and an Iranian (citizens divided by their nationalities but united by their status as victims of remorseless extremism). With each step I took, I found myself wrestling with a persistent unease, an emotional sickness, an overly alert awareness of the smallest movements of those around me. Every second seemed to be an internal negotiation with death. Did I turn and look behind me now or in a few steps? Was it safer to walk in the middle of the street or to the side? The leather-jacketed man next to me — was he a plainclothes policeman, a civilian, or someone more nefarious? Might anyone think that I, a brown-skinned male who fit the “profile,” was a terrorist? “Look how everyone is watching everyone else,” a cafe owner told me not too far from the Bosphorus strait that connects Asia to Europe, East to West. “It has never been like this.”

Parallels are often drawn between the ideology of radical jihad and the fascist movements of the 20th century. Until recently, the term “Islamofascism” was used in some polemical quarters to describe the likes of al Qaeda and the Taliban. Popularized by the late Christopher Hitchens who himself was repurposing Susan Sontag’s 1982 description of communism as “fascism with a human face,” the analogy was off, but only slightly. Radical jihadist groups certainly share with their fascist ancestors a visceral craving for a totalitarian utopia and an explicit subsuming of the individual within the collective, but these same groups lack the mass bureaucratic, corporatist structures that gave fascism its power. Rather, the unrestrained fanaticism and indiscriminate violence of the jihadist death cults who claim to speak on behalf of every Muslim, living and dead, have more in common with the late 19th — and early 20th — century anarchists, who for a time were the greatest threat to democracy and unlike anything the world had seen.

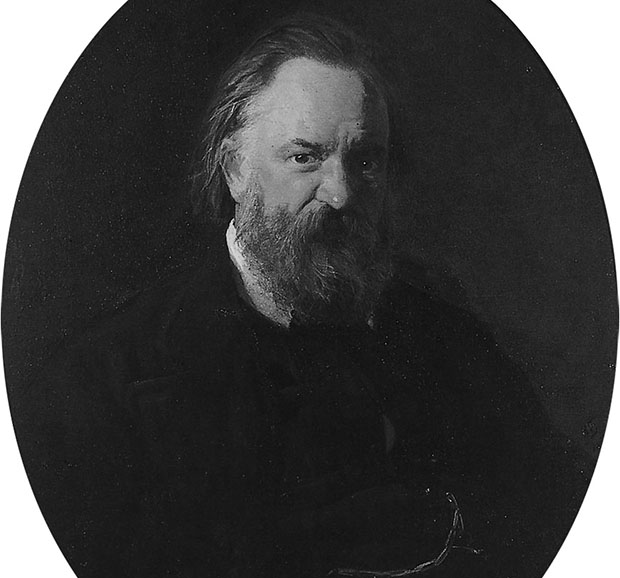

Anarchism comes from the Greek word anarchos, meaning without a chief or a head. As a violent movement, it came to the fore — as revolutionary programs often do — at a time of great uncertainty, a transition period of the kind that the Russian socialist writer Alexander Herzen once described as a “pregnant widow.” Between the death of the old order, “and the birth of the other, much water will flow by, a long night of chaos and desolation will pass,” Herzen wrote. Much like the preceding two decades, the late 1800s and early 1900s were a time of rapid economic growth, imperialism, and globalization. In these years, the United States became the largest economy in the world, and with its victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898 — started, like a more recent war, for dubious reasons and fueled by mendacious journalism — also became an imperial power. Economies were gradually becoming interconnected through the invention of new technologies that upended the old way of life. The QWERTY keyboard (1873), the light bulb (1879), the gasoline-powered automobile (1889), and the airplane (1903) were but a few technologies that offered the promise of individual mobility and peace after centuries of war and famine.

Hardly a more ebullient period existed until this time. Consider how Stefan Zweig recounted what he called the Golden Age of Security in his memoirs, The World of Yesterday:

In its liberal idealism, the 19th century was honestly convinced that it was on the direct and infallible road to the best of all possible worlds . . . People believed in ‘progress’ more than in the Bible, and its gospel message seemed incontestably proven by new miracles of science and technology . . . From year to year more rights were granted to the individual, the judiciary laid down the law in a milder and more humane manner, even the ultimate problem, the poverty of the masses, no longer seemed insuperable.

Latent in Zweig’s words is a creeping recognition that this golden age was coming to an end, and the depravities of European totalitarianism would bear this out and lead him to commit suicide the day he finished this book.

Something similar was taking place in America, but the utopianism of Reconstruction soon gave way to cynicism as a catastrophic financial crisis struck the nation in 1893, coupled with an onset of mass migration into the United States. More than 20 million immigrants arrived in the succeeding three decades, the largest influx of newcomers in any comparable period. The immigrants were slurred and stereotyped as foreign pestilences, criminals, and greedy, uncultured menaces. Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson both condemned what they called “hyphenated Americanism,” with Wilson going so far as to call the hyphenated American a man who “carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of the Republic.”

Economic growth, technological progress, globalization, mass immigration — it was in this context that a violent revolutionary form of anarchism grew to threaten the established order, its ends nothing less than the overthrow of all the institutions of the day, its means, assassination and terror. An American opening her newspaper in these years would have read in horror about one anarchist attack or another. A Barcelona opera house was bombed in 1893; the following year, an anarchist threw a bomb into the French parliament, inspiring Emile Henry to conduct his own attack. Not even world leaders were immune: The president of France was assassinated in 1894, the king of Italy murdered in 1900, President William McKinley assassinated in 1901, the Spanish prime minister shot and killed while taking a bath in 1907. France counted two hundred anarchists in 1882; a decade later, over two thousand individuals in France were considered anarchist, nearly a thousand of them dangerous. The terror had become so widespread that on two separate occasions, world leaders held international conferences to address it.

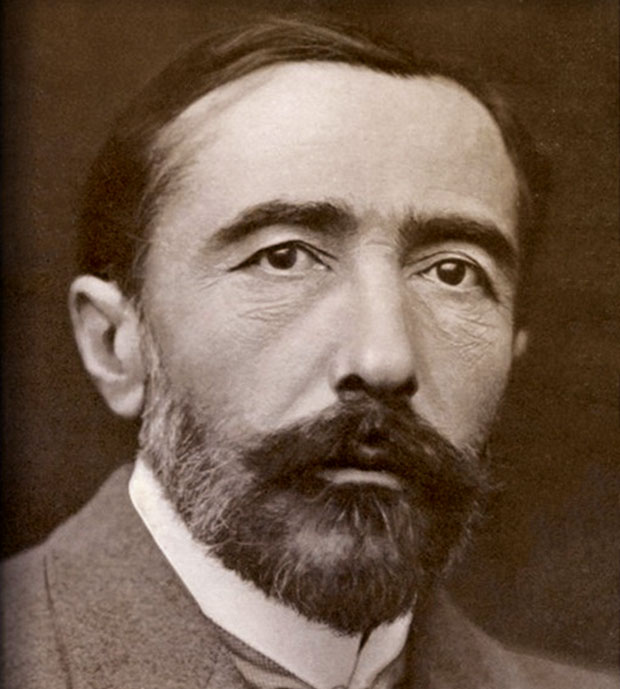

The paranoia engendered by this terrorism found its depiction in literature, most notably in Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel, The Secret Agent. Conrad had been provoked by the real-life attempt of anarchists to blow up the Greenwich Royal Observatory outside London. How to understand this brazen assault on a symbol of rationalism and science? In an author’s note later added to the novel, Conrad called the attack a “blood-stained inanity” whose origins were unfathomable “by any reasonable or even unreasonable process of thought.” The Secret Agent’s most memorable character is a man referred to simply as the Professor, “the perfect anarchist.” Like many of today’s terrorists, he is a jilted narcissist with a technical education. The Professor roams the streets of London with explosives packed under his coat and a rubber ball in his hand; when squeezed, the ball with detonate the bombs on his body and instantly kill everyone around him. At one point in the novel, the Professor’s comrade remarks that there will be good people in the crowd when he commits suicide murder, to which the professor responds:

I am not impressed by them . . . They are bound up in all sorts of conventions. They depend on life, which, in this connection, is a historical fact surrounded by all sorts of restrains and considerations, a complex organized fact open to attack at every point; where I depend on death, which knows no restraint and cannot be attacked.

There it was, clearly adumbrated in this work of fiction from a century ago: the terrorist’s belief in death as a life-salvaging force. Anarchists may have been atheists in the literal sense that they did not accept an intervening deity or paradise, but when it came to violence, death, and everlasting redemption, their devotion to their cause was as cultish and fanatical as the most committed of religious extremists.

In America, anarchists found a home in working-class communities in the cities, most prominently within the Italian-American community. The overwhelming majority of Italians were law-abiding, of course, and historical records show that their arrest rates were lower than that of native-born whites, but from the fringes of this community there emerged a violent anarchist movement led by a charismatic orator named Luigi Galleani.

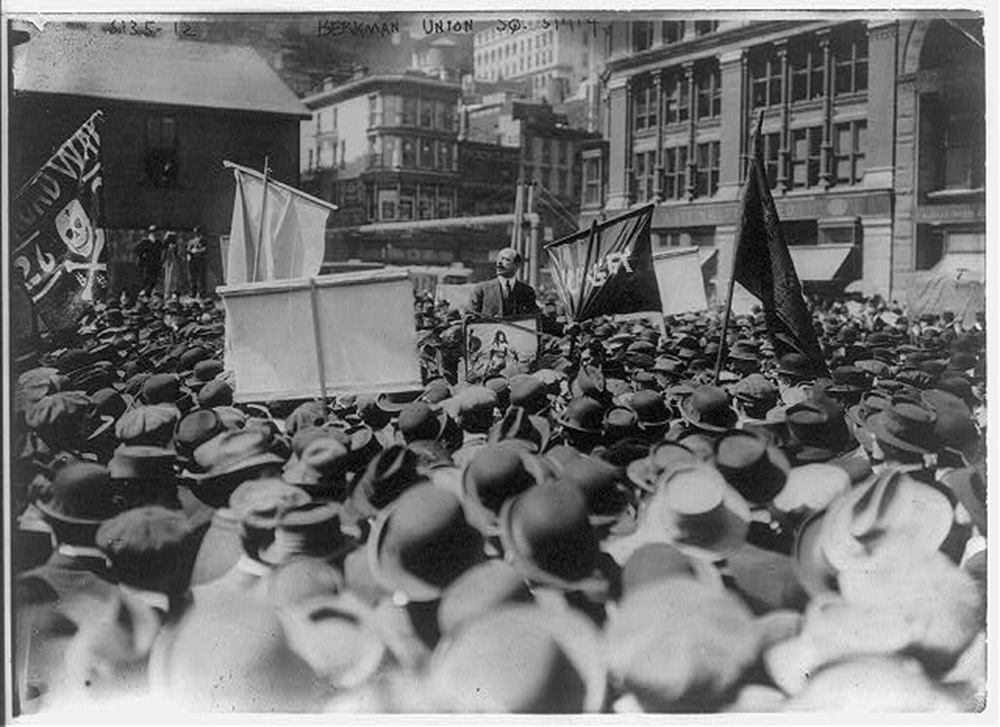

Most of Galleani’s writings remain untranslated and there is currently no biography of his life in English, which is unfortunate because Galleani was perhaps the most dangerous man of this era. Born in Turin, he studied law in his teens before abandoning legal arcana in favor of militant propaganda. Galleani toured the United States, delivering incendiary speeches that extolled the virtues of terror and martyrdom as he propounded his theory that violent anarchist revolution would break the chains of the working class. “Nothing less than the clean sweep of the established order would satisfy his thirst for the millennium,” noted the late historian Paul Avrich. His rallies were packed with radicals from around the country, and those who could not make it to one of the packed halls could read his newsletter which published the names and addresses of powerful officials labeled “enemies of the people.” Galleani even put out a bomb-making manual to help lone-wolves carry out their attacks. By 1908, the New York Times could report that the United States had declared a war on anarchism.

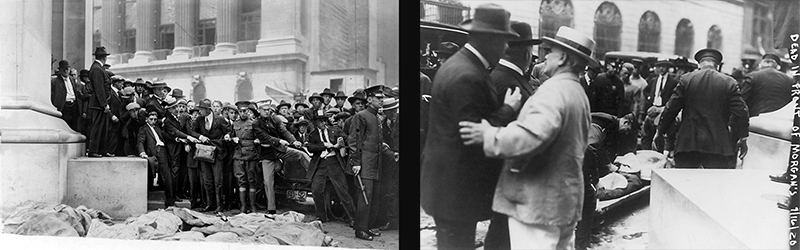

It was not until April of 1919 that anarchist terror came to the United States in the form of a strange package sent to the home of Thomas Hardwick, the recently retired senator from Georgia and the co-sponsor of a major deportation bill. Away from his home, Hardwick’s wife had her black maid, Ethel Williams, unwrap the parcel. As she did, it exploded and tore off both her hands. It quickly became apparent that there were more such special deliveries. Attorney-General A. Mitchell Palmer received a bomb, as did Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the mayor of New York, and business magnates John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan. All escaped unharmed, but the anarchists were just getting started. Two months later, eight bombs went off almost simultaneously in seven American cities including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. Once again, the perpetrators hand-delivered the bombs to the doorsteps of all their targets. At each scene, they dropped leaflets which they called Plain Words: “There will have to be bloodshed . . . there will have to be murder . . . we will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions.” It is a testament to the randomness and — excuse the term — anarchy of history that a near-casualty of this awful attack was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, who was on a walk when the explosions rocked the capital. Had he been a few steps closer to the attorney general’s house, Franklin Delano Roosevelt might not have lived to become president. Once again, the targeted officials escaped unharmed, but the worst assassination plot in American history was followed the next year, 1920, by an anarchist bombing of Wall Street that left 38 people dead in what would remain the worst terrorist attack in American history until the Oklahoma City bombings of 1995.

As one might expect, the Justice Department and Bureau of Investigation overreacted and the press was quickly whipped into hysteria. One senator wanted native born Americans who espoused radical ideas to be sent to a penal colony in Guam. In a single night, 4,000 people were rounded up without due process, informants were employed to entrap suspected radicals, families separated, individuals deported, and even some people thrown into prison for visiting their loved ones in jail. When the attorney-general was called on to testify to Congress, he labeled his critics terrorist-sympathizers. Walter Lippmann, one of the great political journalists of the 20th century, noted the irony in the Wilson Administration’s unconstitutional tactics, describing it as incredible that “an administration announcing the most spacious ideals in our history should have done more to endanger fundamental American liberties than any group of men for a 100 years.” The analogy to the neoconservative freedom fighters speaks for itself.

Not everyone was so mindlessly caught up in the frenzy. Ruling against the Justice Department in a deportation case, one federal judge said the government was behaving like a mob which set out to “hang first and try afterwards.” At great personal and professional risk, twelve eminent attorneys, among them Felix Frankfurter and Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School, issued a report which they entitled, To the American People: A Report on the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice. The criminals responsible for the 1919 bombings were never found, but Attorney General Palmer’s draconian response led him to seek the Democratic Party nomination for President in 1920, ultimately finishing third even as he proudly declared, “I am myself an American and I love to preach my doctrine before undiluted one hundred percent Americans.”

Anarchism would eventually fade as world wars, fascism, and communism, took its place as the greatest threats to peace and security, but for a time the ideology spoke to so many people in the underclass because it convinced them the established shibboleths of the 19th century — progress and technology — had been myths. It covered the messiness of reality and the incomprehensible complexity of modern society with all its changes and impersonal forces. Like anarchism, Islamism and radical jihadism see the Western model of the good society as spiritually empty, and their first marketing point to disaffected youth even of middle-class means is that political Islam will offer them a vision greater than themselves. This is why jihadists, whether they are converts or born Muslim, are “born again” into the religion with ready-made narratives that define their lives, hoping and searching for the perfect worlds of the Caliphate and paradise (whichever comes first).

The struggle against radical jihadism will have to be an intellectual and generational one that isolates the narrative the jihadists tell and undermines it with reference to Islam’s own cosmopolitan and open history. But the battle will be lost if the very liberal democratic principles which Islamists — like anarchists — consider devilish are undermined. If one goes back to September 12, 2001, and asks, “What was Osama Bin Laden after?” the answer is a prolonged war between the West and Islam that draws out for decades until liberal democracy is exposed as a morally vacuous ruse. In the Bin Laden narrative, and in ISIS’s second chapter of this narrative, the West with all of its values would negate its principles and thereby collapse in on itself.

As his trial, Emile Henry had the following to say before he was guillotined:

I had been told that our social institutions were founded on justice and equality; I observed all around me nothing but lies and impostures . . . [Anarchism] is born in the heart of a society that is rotting and falling apart. It is a violent reaction against the established order . . . It is everywhere, which it impossible to contain. It will end by killing you.

Winning for jihadists is not defined as striking a mortal blow to an imperious West; rather, it is chipping away at the limbs of the Western world through a war of attrition until the West disbands the open society, builds more walls, targets the darker-skinned, and eventually asphyxiates itself. The suicide bomber and his various organizations desire a gradual self-immolation of the tolerant society, when one day, years into the future, the average citizen wakes up to find that ISIS and al Qaeda may not have won but liberalism and its values have irrevocably lost. •

Images courtesy of Alexander Berkman and Bianca Dagheti via Flickr (Creative Commons) and Library of Congress, P. S. Burton, Materialscientist, AltCtrlDel, via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).