In the past few months the term misogynoir — the combination of anti-Blackness and sexism that specifically affects the way that Black women are perceived, treated, and represented in media — has been on my mind more than normal. As a Black woman, the realities of how patriarchy and white supremacy collide to conspire against my personhood are not new to me. But the perfect storm of being home watching (what feels like) endless amounts of television, Twitter nonsense, the systematic dismissal of Black women within the Black Lives Matter movement, and the media’s erasure of Black women in speculative narratives that has made me much more acutely aware of the effects of how misogynoir is killing Black women in both reality and fiction.

Speculative fiction use to feel like the only kind of fiction where endless freedom was possible. I remember looking to X-Men as the exemplar of a world that accepts people no matter if they were Black, white, or blue (literally); while The Hunger Games proved that rebelling against unjust systems was not only an option but a right and created real change. Now I see it for what it is another way to sanitize the realities of Black people by creating futures where others who are othered and oppressed are constantly at odds with those who oppress them unless they accept self sterilization from what makes them themselves. Assimilate or die.

Meanwhile, no matter how much we cheer for a white girl rebelling against her government we can’t ignore that District 11 — the only district of Black people — is still sharecropping, living with police brutality and government-sanctioned murder. Oh, and the Black girl, still dies! No matter the world Black women, and girls, are always expendable if they are mentioned at all.

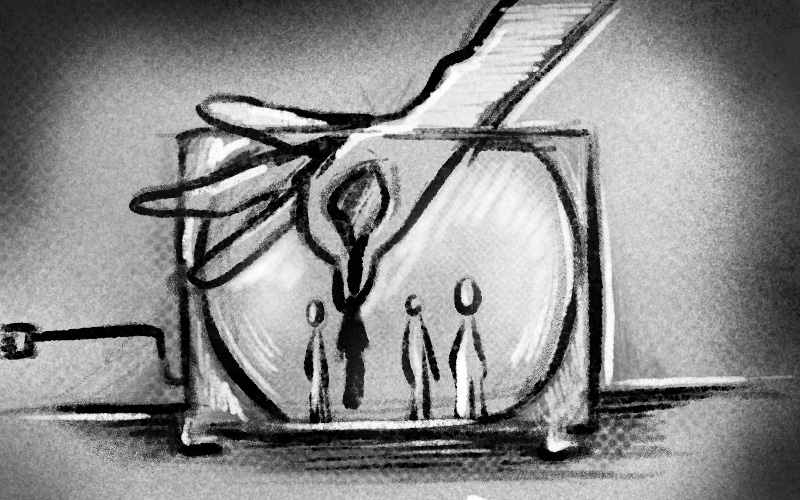

With the world going up in flames, a global pandemic, and a national uprising, speculative fiction might not seem like an important topic to pull your attention to. I know what you’re thinking “who cares about the stars warring when we are fighting nazis?” While that’s a valid point, we can’t dismiss the ways media influences our understanding of and interactions within the world. Once we have taken in enough repeated images of anything, it becomes a part of our subconscious understanding of what is “normal” or at least socially acceptable and expected.

Speculative fiction is meant to take these norms and magnify, subvert, and/or interrogate them so that we can look back at our world with a new perspective, more empathy, and a desire to make real change. However, when popular speculative narratives — the place where people go to imagine what other versions of reality are possible — like the Snowpiercer franchise perpetuate ideas of misogynoir by killing, diminishing, and erasing Black women it matters! By not only reinforcing the news, mainstream media, social media, and the nazis that are shooting people at protests, it also shows that there is no freedom, protection, or care for Black women past, present, or future.

If you’re not familiar with Snowpiercer it is a film directed by Bong Joon Ho released in 2013 based on a French graphic novel called Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand, and Jean-Marc Rochette, which was published in 1982. I first saw the film on Netflix during my freshman (or sophomore) year of college so a year or two after its releases in theaters. The long and short of it is that a billionaire builds a train that is 1001 cars long that is supposedly filled with everything humanity needs to survive until the world defrosts, but, if you want to survive you have to buy your way onto the train. So those who can’t afford a ticket but don’t want to die, fight their way onto the train. As the years pass they plan to rebel against the 1% and democratize the recourses of the train. When this plan fails and the train is derailed and the sole survivors — a little Black boy and an Asian teenage girl — get a chance to create a future free of class oppression on a slightly habitable Earth.

When I first watched the film I was in awe. Joon Ho was able to distill down the complexities of class-based oppression, create beautiful almost dream-like interiors, and talk about climate change in two hours. At the time it seemed like the perfect speculative film with the perfect ending. But, when I rewatched it this year — in anticipation of the new TNT show within the same universe — I could not get over the glaring moments of misogynoir and the ways it prioritizes the survival of Black men (and boys) over Black women.

It’s easy to miss in both the film and the show because of the glaring lack of Black women overall. In fact, the only Black woman in the principal cast of the film is Tanya, played by Octavia Spencer, who is the mother of Timmy, played by Marcanthonee Reis. Her son gets taken from her to work “up train,” which is near first class in the engine. What kind of work is never disclosed but there is an understanding that once someone is taken from the tail (the last car of the train where those who didn’t have tickets are forced to live) they never come back. At this moment Tanya could have become a revelation to the genre. Even though speculative fiction is meant to discuss the ideologies and worries of the society and era that it is created in the vast majority center on white characters, written by white authors, directed by white directors, produced by white producers, and greenlit by white network executives leaving race as an afterthought. Especially those who deal with interlocking oppression — a term the Combahee River Collective coin to explain the ways that when a body is oppressed by more than one factor such as race and gender, like Black women, a new kind of oppression is created that is more than the sum of its part a term. For Black women, we now call this interlocking oppression misogynoir and it permeates speculative fiction to the point that Black women are either relegated to nonexistence or subjected to mental, sexual, and/or physical violence. Black women are so often left out of the conversation about gender and race in real life — think wage inequality, maternal mortality, domestic violence, state violence, incarnation, etc. — that we fall into this liminal space by occupying both spaces we are giving the protections of neither.

Tanya unfortunately is not the exception to the rule. She could have taken charge and usurped Chris Evans’s character, Curtis, to show how Black women often are the leaders and motivators of revolutions and social change because of all that is taken from them. But instead, she sadly falls victim to stereotypes in a pitiful way. When Curtis needs a diversion and Tanya begins yelling that the tail is sick of the food bars that they are given and instead wants chicken and begins chanting “chicken” over and over to give Curtis enough time for his act of heroism. In the end, she dies, of course. Within just a few cars of her son, she is stabbed to death by a white man who works as security on the train. She dies a government-sanctioned death and the camera moves on just as we, the audience, are supposed to. This happens all the time in speculative narratives Black women die, lose a limb, are flattened into stereotypes with as much depth as a shot glass and we are supposed to turn our heads and focus on the hero, the one worth saving, the Black man, the white woman, the white man but never the Black woman.

It’s a story far older than speculative fiction reaching all the way back to slavery — yes, slavery! The narrative, or mythos, of slavery centers Black men. We are supposed to think about a Black man freeing himself by running through the forest, Nat Turner, the Amistad and Cinque protesting for his freedom, overseers “breaking in” enslaved men, and Fredrick Douglass giving speeches. This is because America was built to be a white supremacist hereto-patriarchal society. So, despite Black men’s blackness bringing a history of violence perpetrated by white people being a man still gives them the privileges of patriarchy. Which means that when people talk about Black peoples, oppression, or liberation they are talking about Black men’s oppression and liberation. Leaving Black women to fend for themselves against white men, white women, and Black men. As Michele Wallace said in How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, “we exist as women who are Black . . . being on the bottom, we would have to do what no one else has done: we would have to fight the world,” just to exist in the same narratives.

This brings us to Snowpiercer the television series. Our main character Andre Layton, played by Daveed Diggs, is a Black man who was previously a homicide detective in Chicago before the Earth was frozen. This casting choice falls into the traps of both history and speculative narratives in its belief that to include and represent Black people its sole choice is to cast a Black man. Likewise, the writer’s choice to make him a part of the police force serves to align him even more with the white supremacist hereto-patriarchal ideal by making him a tool to protect and serve white people and their property and further oppressing Black people. Andre Layton might be “a Black” but he’s “a Black” you can feel comfortable rooting for because, in the end, he is on your side.

As the show takes place about ten years before the film Andre is technically the prototype of Curtis but they follow the same basic archetype as the leaders of the rebellion. This could have been fine if any of the other principal female characters were also Black but they’re not. In fact, out of the six women whose stories the first season centers five of them are white, and one of them is Asian. The antagonist (Melanie Cavill), the morally flexible rookie (Bess Till), the love interest (Zarah Ferami), the other love interest and fellow member of the rebellion (Josie Wellstead), and the creator of the night car — think night club meets sex club — and leader of the third class rebellion (Miss Audrey) are all white. The only Black woman who has had any lines so far is Light. We know almost nothing about her except for that the fact that she teaches basic math to the children in the tail — who are not allowed to go to the school on board — and she is able to make a projector from almost nothing. I hoped that before the first season ended she gets her own episode but alas she did not and her character remains an enigmatic background character with no development or storyline.

Now, I want to be clear that I am the furthest thing from shocked about the casting of this show or its continuation of misogynoir themes. Even before the show premiered I predicted every single issue that I have with it now. First, that the only principle character being a cis-hetero Black man would help make white people feel that they had done enough in just casting Diggs to showcase that the show is “diverse” while simultaneously being a safe enough choice that there would, and could, not any real conversations about how class struggles are compounded by interlocking oppressions such as race, gender, class, disability, and sexuality (to name a few).

Second, that all but one of the principle women being White would only further prove the dichotomy of Black = man and woman = white. Additionally having predominately white women as leads would complicate any sex scenes because of the ways that black men are fetishized by white women and the white gaze. Third, that Black women would not be in the show at all, or if there was a Black woman she would be a flat character or the subject of violence.

But outside of that my main issue is with what narratives like this tell their audience without having to say a word. Having a story about of revolution and social change being told through Black men and white women continues to perpetuate the idea that Black men are the ones we are supposed to really fight for while erasing the fact that both of those groups of people have the ability to be the oppressed and the oppressor while completely ignoring whose backs they walk on their way to freedom; Black women.

No matter where you look Black Women have been fighting for freedom during slavery, — Harriet Jacobs, Phillis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman — during the Civil Rights Movement, — Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Angela Davis, Coretta Scott King, Shirley Sherrod — and now with Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, Patrisse Cullors the founders of the Black Lives Matter Movement. There isn’t a time in history when Black women are not fighting for their freedom and everyone else’s. By minimizing Black women down to background characters that we barely see, or, a one-line speaking role without any context while you have a plethora of white women who are given histories, context, and love you reinforce stereotypes. You tell us that Black women are inconsequential at best and disposable at worst, while white women are not only complex, loveable, interesting but necessary. By creating these dichotomies you continue to perpetuate the idea that only some people matter.

These dichotomies transcend the screen. We are witnessing people marching every day in all 50 states and across the world, pulling down statues of racists, burning shit down, demanding justice and change for George Floyd (as they should). But the louder people scream George Floyd’s name the harder it is to hear Breonna Taylors. While George Floyd’s murders were arrested Breonna Taylor’s killers are still working as police officers. While Andre Layton gets to be the hero Tanya is still laying in her own blood. Do you see it yet? The list of Black women who have died — cis and trans — continues to get longer and longer all, while the camera pans to something, deemed more worthy of concern. Black women built the Black Lives Matter movement but are shut out of it. We are told to wait our turn, to be patient, that “we aren’t talking about sexism right now”, and that our focus should be on educating and protecting Black men. We are shown that the survival of Black men and boys trumps our own. We are told to be background characters in our real lives while we die. We die at the hands of police, we die at the hands of Black men, we die bringing our children into the world, we die in this world and every other one that writers can imagine. •