A political pop quiz: which of the following is a quote from Donald Trump’s presidential campaign?

1. “The politicians just talk. In the meantime, the rich ruling elite just ignores [workers] . . . We need jobs. Now. Not later, now.”

2. “How many Mexicans are there in the United States? No one seems to know . . . statistics show that while Mexicans make up approximately five percent of the total American population they commit about 87% of all violent crimes.”

3. “It is our right, as a sovereign nation, to choose immigrants that we think are the likeliest to thrive and flourish . . . most illegal immigrants are lower skilled workers with less education, who compete directly against vulnerable American workers.”

4. “We are devoted to the restoration of the American republic and the preservation of American sovereignty.”

The first portrays workers as victims of the powerful; the second assumes the form of fact to tell a lie; the third employs nationalism to justify xenophobia; and the fourth, more staid and more timeless, casts America as a nation diminished, under threat, and in need of redress. These themes are familiar to anyone who followed Trump’s campaign. But only the third came out of Trump’s mouth — it’s from a speech on immigration that he gave in Arizona. The rest come from extremist propaganda.

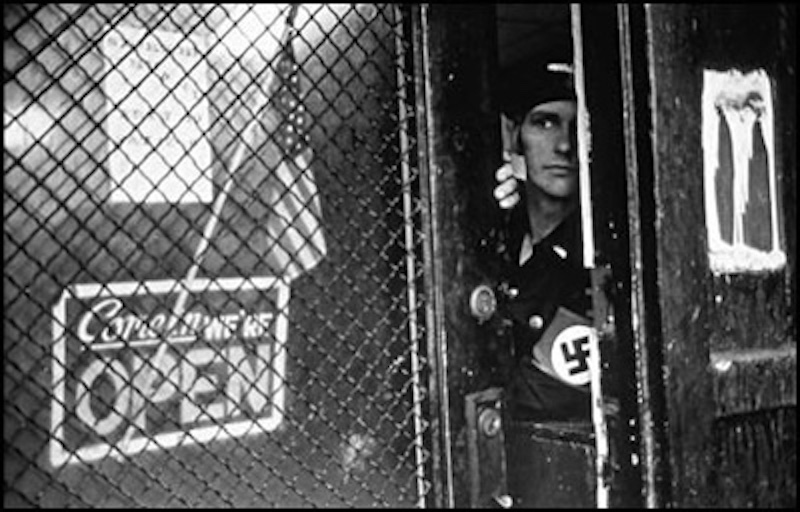

I came across the quotes above several years ago, while working on the Hall-Hoag Collection of Extremist and Dissenting Propaganda at Brown University’s John Hay Library. The collection — which comprises over 700,000 pieces of propaganda — represents the life’s work of a man named Gordon Hall, a self-styled “expert on extremism” who spent the latter half of the 20th century studying American fringe groups. The collection includes hundreds of far-right pamphlets like those excerpted above: the first appears in White Worker, the American Nazi Party’s monthly newsletter, the second in a 1985 edition of the Klu Klux Klan-affiliated White American Resistance, and the fourth in the National Renaissance Bulletin, a circular the white supremacist National Renaissance Party published from the early 1950s until 1972.

I chose those four passages not because they are the only passages from right-wing propaganda that evoke Trump’s campaign — there are many — but because they illustrate several of the themes Trump’s campaign has in common with the literature of the far right. The tropes Trump used in his speeches, debates, and interviews — the corrupt political elite, the decline of the American tradition, the corrosive influence of foreigners on the late, great American way — are the same tropes that have permeated the American radical right for more than 70 years. Trump didn’t awaken the American “alt-right” — he used its messages and spoke in its code.

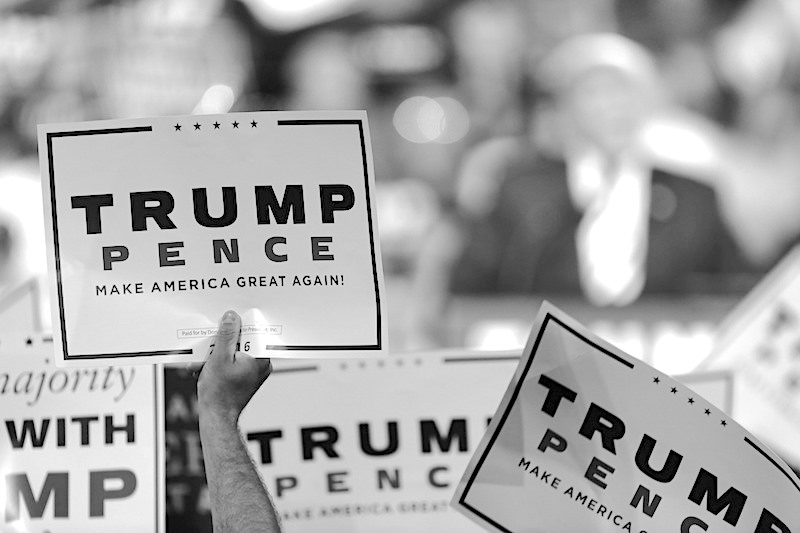

The rhetoric of decline — exemplified in “Make America Great Again” — pervades right-wing propaganda. Decline has a long history in American discourse: In 1685, Increase Mather, a Puritan minister, complained that “the present Generation in New England is lamentably degenerate.” 1685 — only three generations out from the Mayflower! 200 hundred years later, the decay of America had become integral to the platform of the radical right. George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder of the American Nazi Party, described the America of 1967 as “sick, weak, feeble, mad and depraved — dying” in his book White Power; a year later, the National Renaissance Party’s Richard Bayer decried “the general weakening and breaking down of the moral, spiritual, and mental fiber of our nation.” The downward slide continues into the new millennium of far right groups: The American Freedom Party’s 2010 mission statement declares that “America has become unrecognizable . . . immorality and evil have replaced traditional values.” Decline is a persuasive rhetorical tool: It makes fear seem like patriotism, anxiety like prescience.

It’s to be expected, of course, that the leader of a political party would point out problems in the country he wants to lead, in order to then suggest a solution. But talk of decline is different from other genres of political criticism in that it implies a lost halcyon age. The solution to decline lies not in the future — not, as Obama’s 2012 campaign slogan put it, “forward” — but backward, in the “restoration of the American republic,” in the again on Trump’s red hat. The solution to decline is return.

Which is what Trump promised: a return to greatness for America. And what constitutes that lost greatness? The decline Trump campaigned against was at least partly economic, but the vague language he used invited broader interpretations, a sort of verbal Rorschach test. Though he railed against the “disgusting and corrupt media” for putting “false meaning into the words I say,” he didn’t make his message or his positions more specific — “Everything is negotiable,” he said. Trump’s words did not convey information so much as invite those listening to supply their own definitions.

And so, depending on the listener, America’s lost greatness might be economic, military, or religious; it might also be racial. (For Odinists, who are well-represented in the Hall-Hoag Collection, it’s both religious and racial: “The modern world is corrupt and in rapid decline,” writes Wyatt Kaldenberg, the founder of Odinism. He urges Aryans to “return to [their] own Gods and Goddesses,” and he means the Norse pantheon: worship Thor more than you already do, through 3D glasses at the multiplex.) When Trump says he means to make America “great” again, he may not mean that he wants to make America white. But the greatness he wants to return to is, in part, cultural and sociological — and therefore in effect racial. In White Power Rockwell warns that “the flood of people on the way” — immigrants — “will be catastrophic, unless we return to Nature’s plan, and select, not the worst, but the best for survival.” See, for comparison, Trump’s suggestion, in quote number three above, that we select only those immigrants “likeliest to thrive and flourish.” It is here that the connection between restoring the lost America and purifying the current one grows clear.

Corruption and purification are the dominant metaphors in extreme right propaganda. But purity is difficult to understand in the abstract; it’s tied to physical cleanliness. On the extreme right, the idea of purity is most often embodied in race. Take The White American, a 1960s KKK newspaper with the tagline “Racial Purity Is America’s Security.” For the National Renaissance Party, American Jews have caused moral and physical corruption: The Jews’ “sole contributions to American culture have been syphilis and usury.” Even when we use the word “corruption” in its modern sense — the dishonesty of those in power — its archaic connotation of putrefaction and disease lingers, echoes.

Far-right groups link the corruption of race to the corruption of government: Only a depraved institution would enforce desegregation or follow a multicultural agenda. And the media is complicit. Trump has called the press corrupt many times and journalists “the lowest form of humanity.” As the January 2013 edition of The White Worker warns, “the media — one of ZOG’s [Zionist Occupation Government] psychological weapons of mind control — is responsible for the most DIS-EASE in this world. They keep it pointed right at the White race.” Institutional corruption is understood as physical corruption — dis-ease is disease. Hillary Clinton is “nasty.” It would be easy, then, for someone on the far right to associate purifying the institution with purifying the people.

When Trump spoke about corruption, as he frequently did, he used the phrase “corrupt establishment,” describing the “elite” or “special interests” who enriched themselves over working people (see: the “rich ruling elite” of quote number one). Trump invoked the primacy of “workers” with a fervor equal to that of Bernie Sanders, except that Trump’s workers, in the context of everything else he said, comprised only a select group of workers: not elite, not politically correct, and not foreign. And Trump’s solution — his way of returning America to Greatness — was, like the solutions of the racial right, a kind of purification. To Make America Great Again you remove what’s currently Making America Not As Great As It Was. Look at the verbs in Trump’s “Contract with the American Voter”: he will “cut” taxes, “freeze” federal hiring, “eliminate” regulations, “ban” lobbyists, “withdraw” from NAFTA, “cancel” U.N. payments, “repeal” Obamacare, “remove” illegal aliens, “suspend” immigration, and “clean up” corruption. His restoration of American sovereignty is something like furniture restoration: a stripping away, a sanding down.

And, like corruption, we understand purification best when it’s concrete, physical. It’s a Black Lives Matter protester beaten and then ejected from a Trump rally. It’s a Muslim refugee deported back to Syria. It’s a wall at the U.S.-Mexico border. It’s a chanting crowd of people, all with white skin. When Trump talked about decline, he implied a return; when he talked about corruption, he promised a cleansing. He might have been talking about the American economy, but he used a code familiar to the extreme right wing: America has fallen, but it will rise up, and what’s been dirtied will be made clean. (“Donald Trump is talking implicitly,” said the former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke to the LA Times. “I’m talking explicitly.”) By keeping his message vague and refusing to pin words like “America” or “Great” (or even “founder” and “bigot”) down to concrete meanings, Trump allowed his aims to resonate with and affirm the long-stated aims of hate groups. Trump is not the far-right redux. He is its loudest voice. •

Images courtesy of Gage Skidmore via Flickr (Creative Commons) and Romansperson and Christoph Braun via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).