Mina Harker, with her brain addled and her blood poisoned by the vampire Count Dracula, tells Dr. Van Helsing while in the midst of a semi-trance that: “The Count is a criminal and of criminal type. Nordau and Lombroso would classify him, and qua criminal he is of imperfectly formed mind.” As such, Mina tells the men assembled around her — Dr. Van Helsing, Dr. John Seward, Lord Godalming, Quincey Morris, and her husband Jonathan Harker — that Dracula is “selfish; and as his intellect is small and his action is based on selfishness, he confines himself to one purpose.” That one purpose is to return to his native soil in Transylvania. There, contrary to most subsequent film adaptations, Count Dracula is felled not by a wooden stake or the sun’s rays, but by a combination of Jonathan Harker’s kukri and Morris’s Bowie knife. Bram Stoker decided to end his 1897 novel Dracula, which is the Count’s first appearance in pop culture, with an ending fitting only for a criminal dumb enough to return to the scene of the crime.

Elsewhere in the novel, Mina’s observations are echoed by Dr. Van Helsing, the novel’s occult expert who is also a practicing scientist, thereby making him a bridge between the rational and the (seemingly) irrational. Van Helsing mentions that Dracula has the mind of a child, and although the Count first appeared to the doomed Lucy Westenra with a “face of unequaled sweetness and purity,” his true visage is ghastly beyond all imagination. Dracula is actually more beast than man. As evidence, not only does Jonathan Harker see him scaling the walls of Castle Dracula like a giant bat, but when he disembarks from the Russian ship the Demeter, he gallops through the dark coastal city of Whitby as a gigantic wolf.

The echoes of Charles Darwin and the theory of evolution are obvious. Like the villainous Mr. Hyde in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which was published 11 years before Dracula, the Count represents a sort of sub-species — a type of creature that looks and acts human but is decidedly primordial and atavistic. Kelly Hurley uses the term “abhuman” in her book The Gothic Body in order to describe Dracula and his ilk as liminal beings that “unfix” not only the “binarism of sexual difference,” but also the differences between that which is human and that which is other than human. Max Nordau, whom both Hurley and Mina Harker mention, would have simply labeled the undead nobleman as an arch degenerate.

Nordau, a Victorian intellectual who co-founded the World Zionist Organization, believed strongly in the idea of degeneracy. His 1892 book Degeneration makes the point that “degenerate art” is the manifestation of a sickly society. For Nordau, the sickness emanated from uncontrolled urbanization and the unhealthy bodies it produced. The former fed the latter, as Nordau’s various studies of hysteria and neurasthenia supposedly demonstrate. Long before it became a cottage industry, Nordau made the claim that the Fin de siècle exemplified the decline of Western civilization. As part of observing this decline, not only did artists go under the microscope but so too did society’s most loathed element — criminals.

While the late 19th century witnessed a blossoming of the first phase of truly scientific criminology, with men like Alexandre Lacassagne and Edmund Locard greatly assisting in the development of forensics, toxicology, and the modern autopsy report, much of the reading public was captivated by the pseudoscience of the Italian school of criminology. The head of this school, Cesare Lombroso, proffered the notion that such a thing as a “born criminal” existed. Criminality was inherited, Lombroso believed, and could literally be read on the faces of the criminals themselves. Lombroso believed that aquiline noses and bloodshot eyes were the calling cards of murderers, while rapists tended to sport what he termed “jug ears.” Giuseppe Villella, a habitual thief and arsonist from Calabria, became Lombroso’s chief muse and one of the prime examples of his methods of criminal anthropology. Following a post-mortem examination, Lombroso discovered what he believed to be a major indentation in Villella’s skull that was reminiscent of such indentations in the skulls of apes. According to Lombroso himself, at that moment, he saw for the first time “the problem of the nature of the criminal — an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals.” Villella’s large jaws morphed from an innocuous trait into a sign that the deceased rouge had been born “to mutilate the corpse, tear its flesh, and drink its blood” like some rural vampire lifted from Slavic tradition.

Lombroso’s ideas ushered in an era of widespread criminal categorization and measurement. Noses, foreheads, ears, and eyes were all recorded, while others, like the pioneering French police officer and the forefather of biometric research Alphonse Bertillon, began utilizing photography to not only record crime scenes, but to also create image profiles of criminals that would be attached to index cards containing information about the size of the suspect’s ear or the contours of the individual’s brow. These mug shots quickly became standard practice in Paris and the other large cities of Europe and North America. Indeed, while Lombroso’s theories were challenged early on by Lacassagne and other French criminologists, Bertillon’s system of anthropometry would not be supplanted until the advent of fingerprint identification. In the meantime, fiction gobbled these ideas up like manna from Heaven.

Along with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes stories frequently presented Lombroso-esque criminals with their delinquencies permanently etched all over their bodies, Stoker was deeply interested in the new science of criminology and criminal anthropology. Over a decade after the publication of Dracula, Stoker wrote in the North American Review about America’s “‘Tramp’ Question.” Invoking the language of contemporary science, Stoker suggested that the “willfully-idle class” of tramps, vagrants, and other “undesirables” be kept under observation so that they can “easily be located and detained in order to be taught to be industrious.” Such an action was a “necessary duty” and “the essence of good government.” In Dracula, such a government is not present; however, the men of England (including the Dutchman Van Helsing, who, like the others, probably belongs to the wider North European and Protestant bourgeoisie) constitute a sort of highly technical and up-to-date combative arm of middle-class decency against a wandering demon from the Balkans. After all, as much as pre-modern prophylactics like garlic, crosses, and wooden stakes are used against Dracula, telegrams, typewritten reports, phonographs, and kodaks are more often employed during the fight. Many scholars have correctly read Stoker’s emphasis on science and technology as a wider discussion about British civilization versus the “backward” civilization of southern and eastern Europe. As Jonathan Harker writes in his journal upon leaving Budapest, “The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most western of splendid bridges over the Danube . . . took us among the traditions of Turkish rule.” However, only a few observers have pointed out the fact that Count Dracula, a type of invasive species meant to shock and titillate an appreciably xenophobic audience, represents one of Lombroso’s “born criminals” — a savage throwback unsuitable for modern civilization. Furthermore, because Dracula is capable of reproducing himself in the form of other vampires, he represents both the apogee and the source of born criminality in the novel.

For Stoker’s Victorian audience, Dracula’s deviance is quite clear on several fronts. First of all, the Count is not a pure-blood European. During a moment when his pride swells to astronomical levels, Dracula proclaims that his Szekely blood is the final product of numerous invasions from other warlike peoples, from the Ugric berserkers of Iceland to Attila’s Hunnic horde. To Jonathan Harker, all of this posturing is slightly “Oriental,” which befits Dracula’s mostly Asian ancestry. As with the later “yellow peril” novels and stories, which pumped out images of Chinese and Japanese hordes invading the West, Dracula is about a strange foreigner with grotesque dietary habits and customs who seeks to enthrall English women. Some have seen anti-Semitism at the center of this portrayal (Harker does find a large cache of Roman, British, Austrian, Hungarian, Greek, and Turkish gold in Dracula’s castle, which conforms with the old stereotype of the vampiric Jewish banker), but unquestionably the Count is a kind of exotic and supernatural rapist.

As Dr. Van Helsing explains near the book’s climax, Count Dracula is also a cautionary tale about Nordau-like degeneration. As told to him by his “friend Arminus of Buda-Pesth,” Van Helsing relates how in life Dracula was a brilliant “Soldier, statesman, and alchemist.” Unfortunately, despite his interest in science and despite his brave decision to attend the Scholomance (a folkloric school of black magic run by the Devil), Dracula cannot surmount his “faculties of mind” which remain childlike. As a result, the vampire Dracula cannot hide his inward malignancy. Often his face is described as “distorted” or “full of rage,” and after committing his primary crime (drinking the blood of the living), the evidence can be found in the redness of his lips and in the “gouts of fresh blood” which dampen his sleeping chin and neck. After feasting on Mina, Dracula revels in his crime and even taunts his righteous opponents by claiming that he will conqueror their women and turn them all into servants. Like the thief Villella, Dracula feels no remorse for his actions, even when the taint of his hand literally sears Mina’s forehead after a sacramental wafer is placed there by Van Helsing. For this and so many other crimes, Dracula must be executed. When his body turns to dust and evaporates in the Transylvanian air, it’s intended to be a great catharsis for Stoker’s readers. It is not.

Besides all of the shapeshifting and the blood drinking, the scariest moment in Dracula occurs when the Count casually strolls through the city of London during the daytime. Though his powers are weaker, the Count is capable of enjoying the sun along with the rest of humanity. Like the eponymous “The Man of the Crowd” in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, Count Dracula’s greatest power may be his ability to blend in with the metropolitan masses. In presenting his vampire this way, Stoker shows the limitations of Lombroso’s criminal anthropology, for if “born criminals” have the ability to blend in, then their atavistic features may not be so readily apparent until it’s too late. Furthermore, if a “born criminal” can blend in, how many other “born criminals” can’t we see on a daily basis? For all their salvific capabilities, science and technology cannot combat all the intricacies of human degeneration. As such, Dracula may be an uplifting tale about rectifying the English moral order in the face of a foreign threat, but it also shows the inherent dangers of the modern urban landscape. Vampires may be frightening, but thousands of faceless criminals walking among us is a much greater nightmare. •

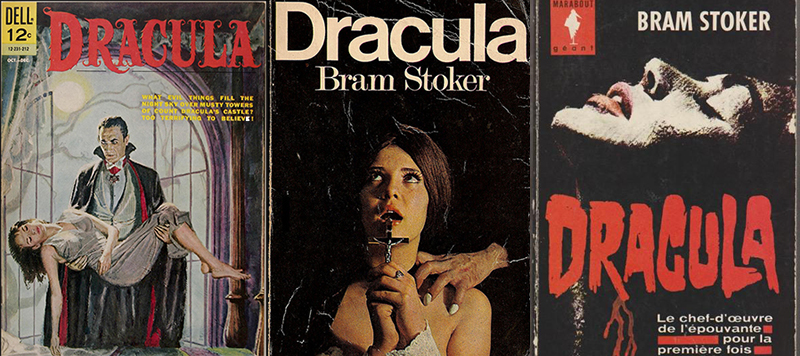

Feature image created by Melinda Lewis with images courtesy of Marxchivist, John Keogh, FICG, tind, helloitserica, seventysevenrpm, Alex Valentine, and Flood G via Flickr (Creative Commons), and Richard Arthur Norton Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons)