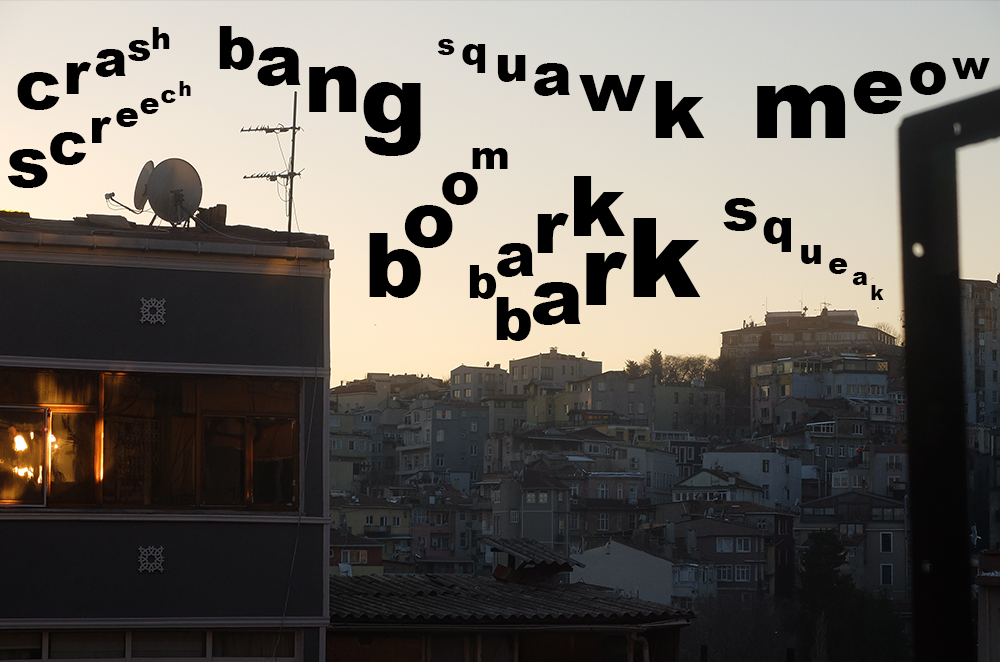

Can you recognize Istanbul with your eyes closed? The ezan, the call for prayer, is particularly dramatic when you are awake early in the morning and the background noise of the city is at a low ebb. At times like these, the muezzin and his recorded song dominate the acoustic landscape. Soon the seagulls chime in. They make you realize how close the Bosphorus is — hardly more than a quarter of a mile away. Why do the gulls start up their awful screeching so early on summer mornings, and why do they settle down later on? Are they motivated by mysterious air currents, changes in temperature, or just competition with their fellow birds?

The small street containing the commonplace building where I live, just ten minutes off Taksim Square, is not particularly beautiful or even picturesque. On the south side, the buildings are packed closely together and painted in a range of pastel tones. A number of them are extremely narrow and four or five stories high. The few buildings on the other side are more widely spaced apart. A fig tree even manages to squeeze between two of them, and another has a garden separated from the street by a high wall. The vine that once connected both sides of the street is no longer there. A dog lives there that might start barking at any time of the day or night. The meowing and wailing of cats, especially in winter, is nothing in comparison. Fortunately, I’m not superstitious, or it might have bothered me to see a metal coffin carried out of the old house diagonally opposite my new home the day I moved in.

During the day, a few merchants known as seyyar satıcı come by. A simitçi walks down the street carrying a round brass plate on which sesame bread rings (“simit”) are stacked in an ornate pile. The fruit seller sometimes uses a megaphone or walks with a partner who repeats his sales pitch even more loudly and aggressively: “patlıcan, biber, domates!” (eggplant, pepper, tomato!). This approach doesn’t scare off the customers. Potential buyers negotiate from their windows, and when a deal is struck, the produce is passed up and the money sent back down in a small basket. Then there is the Aygaz gas bottle seller, who plays a pretty but penetrating tune on a tape recorder: once heard, it can never be forgotten.

The hurdacı, who collects iron, copper, and cables, alerts the neighborhood to their presence with an unmistakable drawn-out cry. So does the eskici, who collects virtually anything that might be of some use, including books and records. He usually drives an old car with an open bed and loudly proclaims his wares.

Now, in the cold season, the boza seller comes almost every evening. Boza is a drink made from fermented wheat, a sweetish beer that you have to get used to before you can enjoy it properly. The bozacı delivers it in small canisters and touts it with a deep and slightly undulating “booooza” (z pronounced like s) which he follows with a rapidly uttered bozacı (his job title), and I wonder whether this is where the word “booze” comes from — or the other way around.

Only in a few cases are these voices attached to a face. Sometimes, I hear a familiar pitch in a neighboring district; that gives me an idea of the catchment area they serve. I tell myself that gentrification can’t be all that bad if these traders are still working these days. They seem like anachronisms, but they are very much part of the present too. I like the idea that these voices, echoes of the past, convey something of life here some 50 to 100 years ago, maybe even during Ottoman times.

During Ramadan, which has fallen in the summer months in recent years, the drummers, a few boys, are the ones who make a loud din in the middle of the night, reminding the faithful that it is time for a meal. At the end of Ramadan, they come again during the day, going from house to house to ask for a few coins. And every few weeks, groups of young men parade through the district, celebrating the coming of their military service and firing blank shots.

I’ve read somewhere that Istanbul is one of the cities most notorious for noise pollution. I have developed a kind of immunity; at least, I no longer hear the more unpleasant sounds such as construction noise and car horns with the same intensity. But in parallel, my senses have become more finely attuned to all the other sounds and cries that collaborate to produce an unrivaled cacophony. That came as a surprise to me.

There is an Anglican church nearby whose bells can be heard clearly ringing in the mornings. In the evenings, I can sometimes make out rhythmical singing. I wanted to know where it comes from. The source turns out to be from the nearby mosque: a group of Sufis who belong to a kind of Muslim brotherhood, singing themselves into a trance.

All these voices and sounds superimpose themselves with rhythmic regularity onto my street. You can’t tell when they are going to erupt, but they are guaranteed to return. There are occasional exceptions — unforeseen, unintended, unwelcome. In the middle of July 2016, in the dead of night, just a day after the attack in Nizza had happened, jet fighters flew so low over my apartment that the window panes shattered from the shock waves: quick-wittedly, I turned on my sound recorder. It was an ear-splitting noise, like a long incision, which lasted no longer than a few seconds. It was related to the attempted coup which I’d known about for a few hours at the time. My friend in Ankara messaged me that things had gotten “nasty” there — and when I read it, I didn’t yet know that Parliament had just been bombed. After the planes flew over, I will never forget the cries of the startled seagulls and crows that lasted for half an hour. And the serenity of my neighbors as they tried to imagine what had happened. It was only later that I learned about the terrible things that had taken place on Bosphorus bridge.

Sometimes, I listen to my short recording of the jet fighters flying over to recall the thoughts that crossed my mind at the time. Surprisingly, I didn’t panic even though I didn’t have much food or cash at home and couldn’t get to the ATM only five minutes away. I only left the house the following day, after a short and very restless night. The recollections of this night will stay with me.

The bats that flit along the street in the twilight produce the merest whisper of noise. It may be that their faint sound is only in my head. Although I can make them out, I still haven’t been able to tell how big they are. But I like to imagine that they are little spirits that gently caress the street to sleep with their wings as the night deepens. The person who climbed in through the open window of my apartment one searingly hot night two weeks after the attempted coup and left again the same way with my smartphone, laptop, and camera with him, did not make the merest sound. He couldn’t interrupt my slumber.

And while Orhan Pamuk once wrote that Istanbul is “a city that newly arrived Westerners are at a loss to understand,” I take up the challenge and continue to prick up my ears. •

Translation by Lucy Jones.

Images courtesy of the author and manipulated by Isabella Akhtarshenas.