One of my favorite musical subgenres is what I like to call “nervous breakdown records,” or classic albums that were made while the artist in question happened to be in terrible distress. Some titles might come immediately to mind, like Dylan’s post-divorce Blood On The Tracks or Pet Sounds, Brian Wilson’s green-eyed attempt to outdo The Beatles. You could also add Sinatra’s despondent In The Wee Small Hours, Van Morrison’s transcendent Astral Weeks, or Bruce Springsteen’s harrowing Nebraska, just to name a few.

But those are all sad white dudes. Let’s not leave out the ladies — Joni Mitchell’s Blue, Billie Holiday’s elegant Lady in Satin, and Richard and Linda Thompson’s world-weary I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight all deserve equal recognition for plumbing the depths of what Yeats once called “the deep heart’s core.” But my personal favorite of this lovelorn genre has to be Dusty In Memphis, by the tragically glamorous Dusty Springfield.

By 1968, when Dusty started working on Dusty In Memphis, she was already a big star. She’d become an icon of swinging London with buoyant pop tunes like “I Only Wanna Be With You,” “You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me,” and “Wishin’ And Hopin’.” All of those songs, and plenty more, proved that Dusty could belt it out with the best of them, but she also knew how to caress a melody, and she did definitive versions of songs written by masters like Burt Bacharach, Randy Newman, and Carole King. Her subdued version of “The Look of Love” still smolders, as does her version of “Spooky” and “I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself” (also covered fiercely by The White Stripes) is magnificent.

It wasn’t just the music; Dusty was fashion trendsetter as well. Sporting glittering gowns, big platinum bouffants, and heavily mascaraed eyes, known as “the panda look.” Without getting the credit she deserved, she also capably produced many of her own records and insisted on exploring different styles, like show tunes, jazz standards, and the speak/songs of Jacques Brel. As a cultural pioneer, she made sure to include tributes to Motown, Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, and R&B in her personally curated TV shows. Dusty acted as a musical diplomat who helped to further promote American, and specifically African-American, music across the pond.

Given all this, it made perfect sense that Dusty would eventually wind up recording in America. For lots of British artists (and to the dismay of some) conquering America is proof that you’ve really made it to the big time. For Dusty, the chance to record stateside was equal parts thrilling and nerve-wracking. Even though in some ways she was the epitome of a confident, independent, modern woman, there were still demons. Lots of people testified to Dusty’s fun-loving, lively personality, and sense of humor but she could also be extremely neurotic, insecure, and erratic. She was prone to heavy bouts of drinking, smoking, drugging, and diva-ing. The naturally shy, deeply Catholic London Irish girl who was born Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien eventually discovered, as many in her situation do, that her pop stardom provided a glittering mask that almost ended up eating her alive. She later confessed that the bigger-than-life persona of “Dusty Springfield” started to leave her with very little idea of who she really was beneath all the glitz.

To make matters worse, to record in the American south to try something new meant that Dusty was simultaneously both in her element as a lover of music and totally out of it as a stranger in a strange land. Recording with a crack team of Memphis musicians presented both a challenge and an opportunity. To sing in the home base of idols like Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin proved to be terrifying. Dusty suffered intense stage fright even while recording alone in the studio and started spending hours putting on her makeup (a typical go-to during stressful times) and feuded with the producer about the choice of material. There was a now very contemporary concern about cultural appropriation — how could a white English woman like Dusty, as gifted as she was, dare to try and sing in one of the epicenters of African- American music? Dusty was very hip in her home country (which was decidedly less hip, at times, with some music papers awkwardly “complimenting” her vocals with comparisons to black artists) and light-years away from being a racist, but the anxiety of influence was still gnawing away at her already delicate psyche.

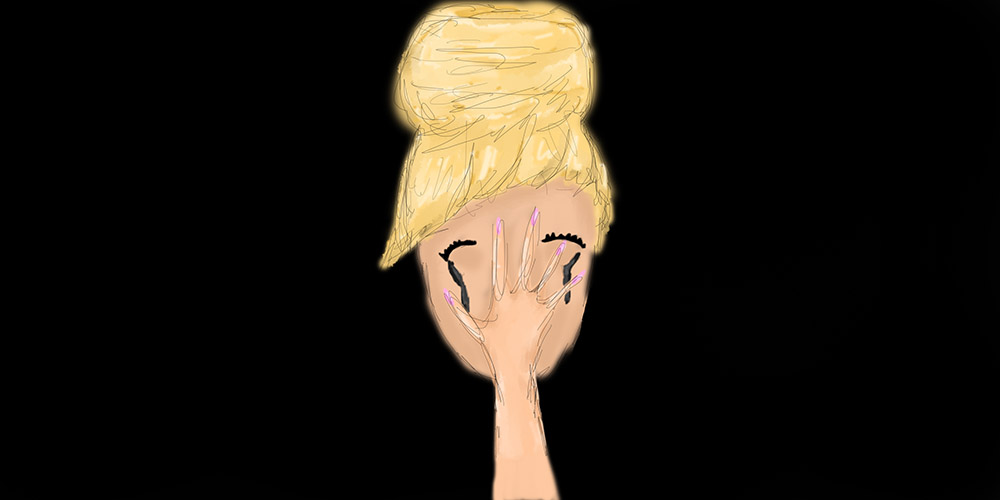

The cover photograph illustrates this tension and sets the tone for the record as a whole. Through a sepia haze against a black background, Dusty’s dark-ringed but piercing eyes peer out apprehensively above the hands held self-protectively up against her face, as if in embarrassment or chagrin, her lacy shirt cuffs swooning to the sides, looking like a stiff wind or stray remark might knock her over. This is a portrait of a gifted and successful singer who has recently turned 30, somewhat lost in the American scene, who just doesn’t know what to do with herself. Dusty may not have realized or dared to believe it at the time, but she was about to make the greatest record of her life.

The opening track “Just A Little Lovin’” establishes the motif of sexuality as a many-splendoured thing, which is one of the record’s preoccupations. The lovely undulating melody cheekily praises the philanthropic joys of morning sex, which “beats a cup of coffee for starting off the day.” Hard to argue with that. As the strings swell, Dusty’s gentle but firm mezzo-soprano soars with the sublime notion that “this old world/ it wouldn’t be half as sad/ it wouldn’t be half as bad/if each and everybody in it had/ just a little lovin’.” Amen to that, sister. “So Much Love” is just as open-hearted, a big declaration of bliss and lifelong devotion to the one who provides it. The relative banality of the lyric (“SOOO much LOOOVE to GIIIVE you”) is enriched by how fully Dusty commits to the rapturous, billowing vocal.

“Son of A Preacher Man” is the best-known song, and was culturally revived from its inclusion in the Pulp Fiction soundtrack. The insinuating guitar line opens the sly, knowing ditty about the rapture of teenage lust with the son of the church. The song is part of the lineage of naughtily gospel-tinged come-ons that subtly (or not-so-subtly) relate sexual and spiritual ecstasy, like Al Green’s “Take Me To The River” and Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say.” Dusty testifies with just the right meld of innocence and experience, punctuated with those soulful but wisecracking Memphis horns, stirring in a little flirty innuendo (“learnin’ from each other’s knowin’/ lookin’ to see how much we’d grown”) to sweeten all that sneaky sinning going on far away from where the church folk gather.

Let’s not forget that “reach” — as in, “the only boy who could ever reach me” — is southern slang for when someone can, well, you know, “Take You There.” No less an authority on sex, God, and the blues than Aretha Franklin, a minister’s daughter herself, gave it her stamp of approval and later strutted her way through her own version. Legend has it that after meeting an awestruck Dusty in a Memphis elevator she just grabbed her arm and said “girrrlll!” So much for fears about cultural appropriation.

Randy Newman’s desolate domestic drama “I Don’t Want To Hear It Anymore” eavesdrops on the disintegration of a relationship within the claustrophobia of a shabby apartment block, where “the talk just never ends/and the heartache soon begins/ the talk is so loud/ and the walls are much too thin.” As is the way of small towns, everyone is into the narrator’s business as the string section climbs the walls and the whispering disdain of backing vocals murmuring “he’s not thinking of her today” capture what it’s like when everybody knows a relationship’s over except for the ones who will ultimately deal with the fallout. The outro’s plaintive refrain, “don’t want to hear it/ can’t talk about it” pulls the patchy blanket of denial over the whole scene.

If you ask me, the record’s true masterpiece is “Breakfast In Bed.” The threadbare glamor that flits like a firefly throughout the whole record meets the quiet desperation of emotional and physical needs. It’s one of those songs that seems like the plot of a classic film or short story. The whole scene is set with those aching first lines: “You’ve been crying/ your face is a mess/ come in baby, you can wipe the tears on my dress/ She’s hurt you again, I can tell/ I know that look so well.” There’s a world of half-conscious emotional manipulation in those lines, sketching out characters whose raw needs overpower their self-respect: “And no one has to know, I’ve come here again/ Darling it will be like it’s always been.”

The song’s whole atmosphere is seductive, tender, and a little creepy. The horns crackle behind her as Dusty sing/speaks the lines like an aged ex-debutante who’s long past her glory days but still possesses some ineffable allure. The syllables’ hard b sounds become velvety v’s, that hover like an expensive perfume. There’s even a sly nod to her swinging London past with the not-quite-throwaway line “you don’t have to say that you love me” which was a bold declaration of sexual independence a few years before, and now suggests the character’s urge to fill her empty bed with the ghosts of the past. In “Just One Smile” Dusty plaintively asks, “Why can’t I cry a little bit/ There’s nobody to notice it/ Can’t I cry if I want to/ No one cares.” When the chorus kicks in and the orchestration swells, Dusty still sounds like someone who is fighting back tears. Her voice carries enough echo and reverberation in the mix to imbue it with a grand vulnerability like she’s singing her heart out in the middle of an empty ballroom.

The haunted atmospherics of “Windmills Of Your Mind” takes this profound loneliness to its farthest possible reach. The disorienting strings whirl like pinwheels as the lyrics maddeningly add simile on top of surreally unrelated simile (“round, like a circle in a spiral/ like a wheel within a wheel . . . like a snowball down a mountain/ and the world is like an apple turning silently in space”) which feels almost as disconcerting to listen to as it apparently was to sing. The final take left her almost totally out of breath, hyperventilating while trying to keep up with the song’s accelerating momentum. “In The Land Of Make Believe” has an exotic, almost ethereal atmosphere with a delicate arrangement of plucked sitar and conga. The instrumentation hangs in midair like cigarette smoke and quietly accentuates Dusty’s near recitative of the lyrics.

There’s some ambiguity about the true nature of Dusty’s sexuality, though it seems widely understood that she preferred women. She wasn’t necessarily closeted; she told inquiring interviewers that she was interested in both men and women. A song that gracefully considers the possibility that one’s happiness can only truly be found in some other world, a magical land beyond the drabness of reality, connects to one of the subtle tropes that appear in queer narratives, thus taking on a slightly more subversive meaning than mere daydreaming.

Sometimes other musicians are best at describing what makes a great record great. In his liner notes to the essential 2002 reissue, which is loaded with fabulous bonus tracks, Elvis Costello claimed that Dusty’s singing was “among the very best ever put on record by anyone” and perfectly describes how her tone sounds “like some kind of vapor.” Costello wisely says that “Son Of A Preacher Man” and “Breakfast In Bed” are a couple of the “most knowingly adult records ever made.” There’s an ineffable longing coursing through Dusty In Memphis that is already found in most popular music, but there’s also a rarer maturity about the psychic toll all those extreme emotions can take. The plangent way that she exhales the line “your toy balloon has sailed” speaks volumes about what time takes out of you.

Dusty In Memphis offers a gorgeous demonstration of how to capture that mysterious symbiosis of pleasure and pain in song. For an ambitious, complex, gifted woman who was determined to succeed on her own terms and was almost smothered by fame, surviving it all is a real accomplishment. When she triumphantly belts out that “I found my way out of the darkness” it’s the sound of a deeply personal victory over world’s external and internal pressures, and we can raise our hands in triumph along with her, especially when we’ve heard what it was like for her to get there. •