Dogs were “the first large creature who would live with men,” Barry Hulston Lopez writes in his classic of wolf-literature, Of Wolves and Men. But there are different theories as to when wolves and humans came together and how exactly the transition from Canis lupus to Canis familiaris came about. Did shy wolves approach humans because they found out that there was always something to feed on in their surroundings and slowly got used to their company? Or did humans find lone wolf cubs and rear them? Do our dogs derive from a line of wolves that no longer exists?

We don’t know. It probably took the wolves, now in the company of humans, thousands of years to slowly change their appearance. There is a big difference between tamed wolves and the dogs we know today — without selective breeding the genetic makeup wouldn’t have had a chance to change. While some wolves developed into dogs, possibly at different places on earth, the wolves in the wild continued to exist. Especially during extreme winters when game was harder to find they are known to have come close to human settlements to prey on their livestock and to attack humans — although this is extremely rare. A study by the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, compiled by a number of leading wolf experts across Europe, states that from 1950 to 2002 there have been nine deadly attacks of wolves on humans in Europe and the same number in Russia.

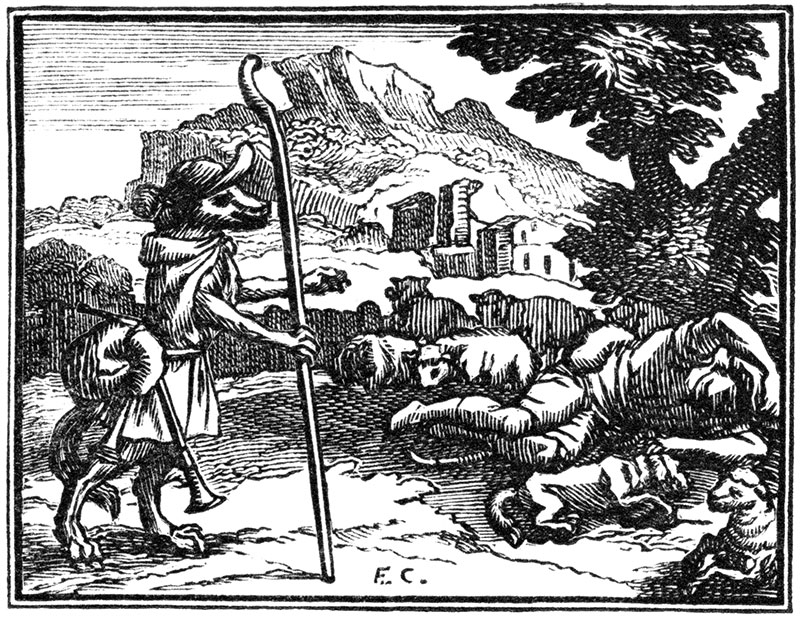

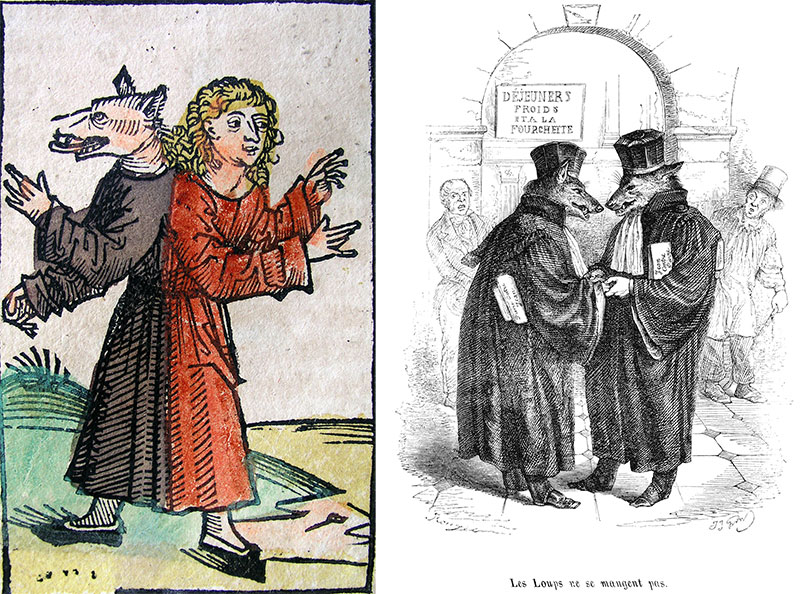

There is hardly an animal that so often produces conflicting emotions as the wolf. The many stories about humans and wolves span the whole range from attraction to revulsion; they are inspired by both facts and fiction. The story of Romulus and Remus, for example, plays with the idea that there must exist a secret bond between the two species. Then there is the story of Little Red Riding Hood, which probably goes back to the Middle East. The girl walks across the forest to visit her grandmother and finds herself in bed with a wolf dressed up as her grandmother (he has devoured her). There are countless variations of the tale: some crueler, some tamer. There is the curious case of Misha Defonseca, who claimed to have run away from the home of her foster parents in 1940 during the German occupation of Belgium because she wanted to find her parents who had been abducted to Ukraine. To hide from the Nazis, she lived with a pack of wolves. In 1997, she published her memoir, Living with Wolves, which became a bestseller. Around the time it had been made into a movie ten years later, the story was uncovered to be false. Monique de Wael, her real name, was in fact enrolled in a Brussels school during the time.

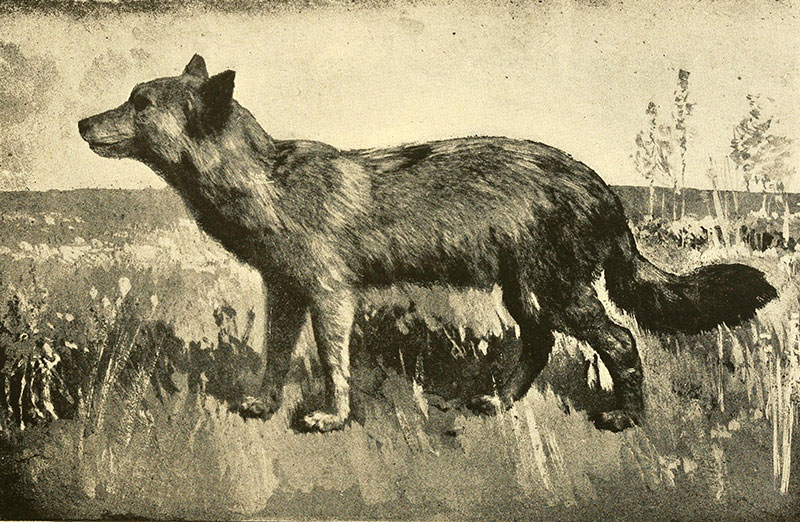

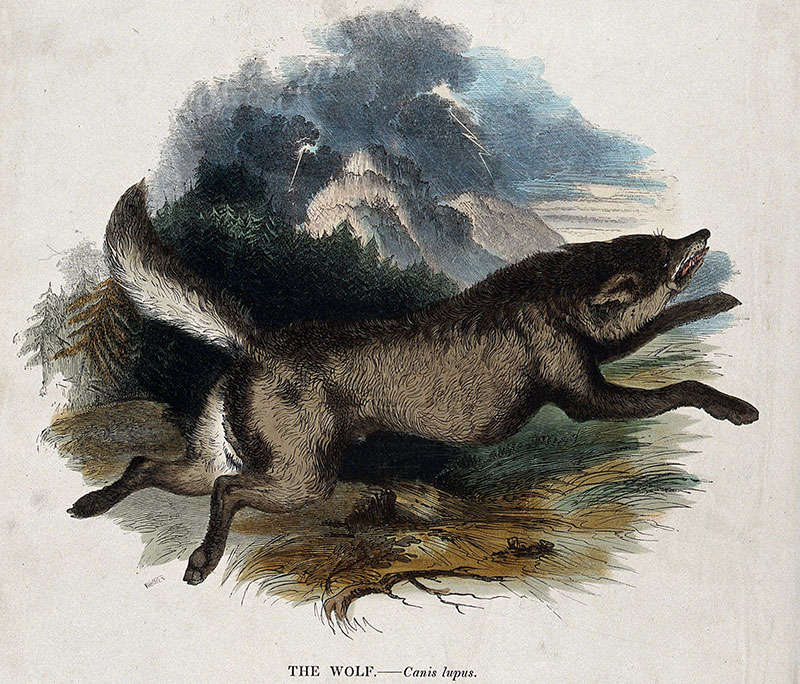

The wolf remains a mysterious creature. Barry Hulston Lopez also mentions some of the most common misconceptions about wolves: “Whenever I have spoken with people who have never seen a wolf, I’ve found that the belief that wolves are enormous is pervasive. Even people who have considerable experience with the animal seem to want it to be, somehow, bigger than it is.” But even where the biggest wolves are found in Alaska, a wolf weighing more than 120 pounds is uncommon.

Completely extinct in this country for about 150 years, wolves have reappeared in the lesser-populated regions of Northern and Western Germany since the year 2000. Genetic examinations have proven that they came into the country on their own from neighboring Poland and Austria. Ten years earlier, in 1990, a federal nature protection law came into effect that protected wolves from hunting. In fact, since this point in time, wolves have profited from the highest possible protection standard, which helped to pave the way for a return of these animals.

As long as they find enough food, wolves have proven they can adapt easily to a new environment; they don’t need complete wilderness. On the other hand, they avoid areas that are developed or where they cannot find enough game (or livestock like sheep and goats), causing the population to always be rather uneven from region to region. And overall numbers are still so low in Germany — currently there are about 31 packs — that they are threatened with extinction in this country. More wolves from other populations are necessary to secure genetic variability and long-time survival, but whether or not they can be considered part of the greater eastern European family of wolves is debated. Scientists are surprised and even overwhelmed by some of the questions now coming up.

Wolves hunt the animals that are easiest to reach. Occasionally, there are reports about wolves killing flocks of sheep when game is not readily available. The examination of saliva samples, and sometimes video footage, then helps to determine the gender and origin of the wolves, data which is then passed on to the National Reference Center for Genetic Examinations of Lynx and Wolf. Farmers receive financial compensation for their killed livestock. In some instances, the predators were proven to not have been wolves actually, but dogs — as could be determined in an incident that occurred in late February this year in North Rhine Westphalia.

The return of wolves to Germany remains a challenge on several levels. In some areas of Germany, scientists, conservationists, hunters, foresters, and representatives of public authorities are developing concepts for how to best deal with the occurrence of wolves. There are various efforts to teach people how to deal with wolves when they appear in their neighborhood. While many people welcome the animals as an enriching environmental factor, others are uneasy, especially with regard to the danger to children. A tool called “flock protection set” has been devised by the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union. It costs a few thousand euros and comprises a motion-sensitive camera and electric nets with white ribbon that can be installed quickly when necessary, in places where no permanent protective fences that reach all the way to the ground have been built. Wolves are able to jump over ditches easily, which is another challenge for keepers of livestock. Some shepherds are getting donkeys, because their shouts are said to drive wolves away. Then the dogs whose task it is to keep wolves at bay can be dangerous to humans, too, which complicates the situation further. There are 500 so-called “wolf ambassadors” in Germany who try to help overcome prejudices, and there is educational material for use in kindergartens and elementary schools. There are 140 wolf ambassadors in Lower Saxony alone, who are also in charge of monitoring the tracks of wolves. That’s two ambassadors per wolf.

Friends and enemies of the wolves face each other — there is the full range from naiveté to hysteria. Some exaggerate the numbers of wolves and attacks, some play the risks down. The discussion about wolves in Germany reached new heights recently when there were observations of an animal that behaved in a way it was not supposed to. The wolf attacked the dog of a family and by doing this already overstepped a boundary. How had he become so fearless? An expert called from Sweden was commissioned to explain the situation, to find a way to correct his unacceptable behavior — to no avail. There was a report of an incident where this wolf is said to have followed a young mother with her four-year-old daughter sitting in a stroller. However, this doesn’t mean that the animal would have attacked, and there is no way to know. Everybody involved in the process of “managing the wolves” realized that there was a lot at stake, because killing the wolf would mean the first such case of more than a hundred years in this country. A brief discussion on whether the wolf should be confined was responded in the negative — a wild wolf in a cage wouldn’t have made any sense at all. It was ordered to be shot. There is a commonly accepted rule that wolves that become habituated to people must be quickly removed.

There was consensus on the decision to shoot him, because otherwise the chapter of the return of the wolves in Germany might have been closed before it had really come under way. His fans called him “Kurti” — a diminutive of the somewhat old-fashioned German first name “Kurt,” and it may just be a strange coincidence that “Kurt” means “wolf” in Turkish. Just the fact that the animal has been quickly given a human name may be understood as indicating that it cannot be dealt with on its own terms, as an animal. Ten years ago, a somewhat similar case of a free-roaming brown bear in Bavaria — quickly dubbed “Bruno, the problem bear” — spurred similar fears before he was shot. He is now on display in Munich’s museum of natural history.

The age-old story of wolf, human, and dog hasn’t come to an end yet. The relationship of humans and wolves remains a vexed one: Because it can never be totally free of conflict, it constantly tests humans’ understanding of what wildness means and how far it may go. If humans take up the challenge and discard the myths, this may teach people a more realistic and more honest understanding of nature. The return of the wolves to Germany is both spectacular and controversial. The animals are beautiful, smart, and usually extremely shy of humans. Europe would certainly be poorer without them. New cubs are expected to be born this month. New packs, new territories, new controversies lie ahead. •

Feature image courtesy of Bukowskis via Wikimedia Commons. Article images courtesy of Codex, Robert Ramsay, Philippe, Wellcome Images, Hartmann Schedel, and Granville via Wikimedia Commons and Robin Fabre via Flickr (Creative Commons).