Several great or powerful American films have yielded signature lines of dialogue to remember them by: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn;” “We’ll always have Paris;” “I coulda been a contender;” “Go ahead, make my day.” Of all John Ford Westerns, several of them truly great, only one of them produced a signature line: John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, remembered for “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” This line is remembered superficially, and most viewers don’t perceive the raw emotions and brutal reality that the statement embraces. And it has meanings and contradictions that resonate today, perhaps the most interesting of which have to do with contemporary notions of masculinity.

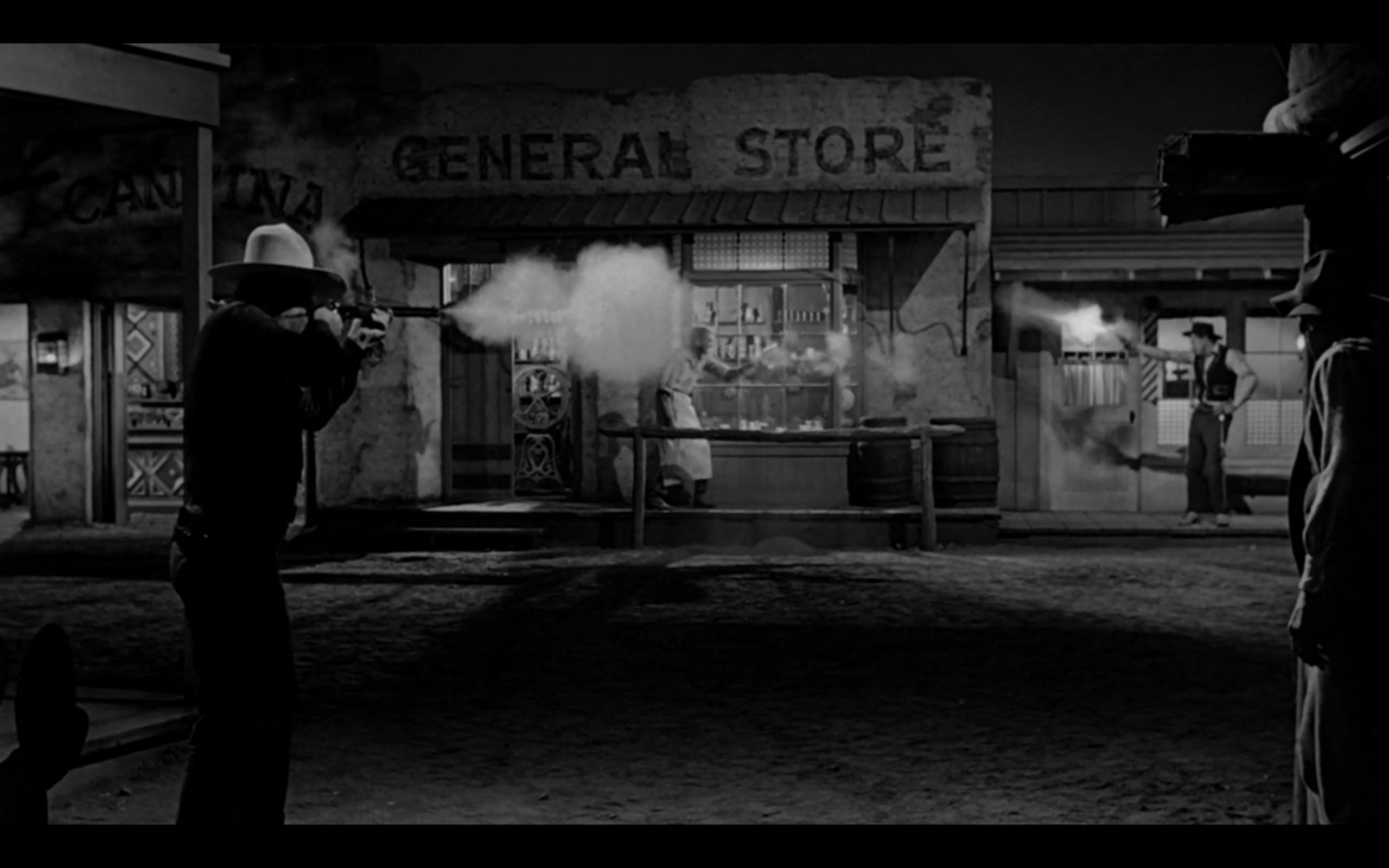

First, the legend. Young, idealistic, newly minted attorney Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) has heeded Horace Greeley’s famous advice and headed west to Shinbone (precise location unspecified; geographical features mentioned or filmed suggest both southeastern Colorado and southern Arizona, hundreds of miles apart), where he intends to set up a law practice. His stagecoach is held up by the vicious Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) and his henchmen just before it reaches Shinbone. Defending a female fellow passenger, Stoddard confronts Valance and is savagely beaten for it. Valance hates what Stoddard represents: decency, principle, education, and, especially, law. Stoddard is brought into Shinbone, where he is cared for by Hallie (Vera Miles) in her parents’ eatery. While recuperating, he starts teaching Hallie and other residents how to read and write and what the rule of law means. Meanwhile, Valance has it in for Stoddard, and tells him either to leave town or face him in a shootout. Although encouraged to flee, Stoddard refuses to run. He has adopted as a maxim something Valance said to him at the hold-up: Out here, a man solves his own problems. Sensing he would have to face Valance, Stoddard has practiced shooting, but he is inept with a six-gun, and it is assumed that Valance will kill him easily. Valance taunts Stoddard, wounds him, and then decides to finish him off with a shot “right between the eyes.” As he fires, so does Stoddard, and to everyone’s surprise — and delight — it is Valance who falls dead. Stoddard wins Hallie by his bravery and becomes a hero, and for this reason, as well as his probity and knowledge of the law, he is elected to be the first national delegate of the statehood-seeking territory. He becomes the new state’s first governor, a three-time senator, the Ambassador to the Court of St. James, and a man who would be a shoo-in for nomination as a candidate for vice-president.

That’s the legend, told (except for the later accomplishments) in a flashback (which takes up most of the film) narrated by a now-elderly Stoddard. He has come back to Shinbone with Hallie to attend the funeral of one Tom Doniphon, whom hardly anyone in Shinbone remembers. The editor of the town newspaper learns of Stoddard’s visit, and he demands to know why Stoddard has come all the way to Shinbone to pay respects to the unknown Tom Doniphon. Reluctantly at first, Stoddard tells him. His account includes the above-mentioned Shinbone elements of the legend, and a whole lot more. We learn that Doniphon (John Wayne), a tough, rough-edged, uneducated settler, is the one who brings the badly beaten Stoddard into Shinbone and delivers him to Hallie’s care. And that Doniphon is in love with Hallie and assumes she will be his. He once brings her a lovely cactus rose, which she then has planted just outside the eatery (also her family’s residence). He is building an addition to his simple cabin outside of town which will include a special room and a porch for Hallie. He senses Stoddard is a rival for Hallie’s affections, yet tries to help him by showing him how to shoot (with little effect).

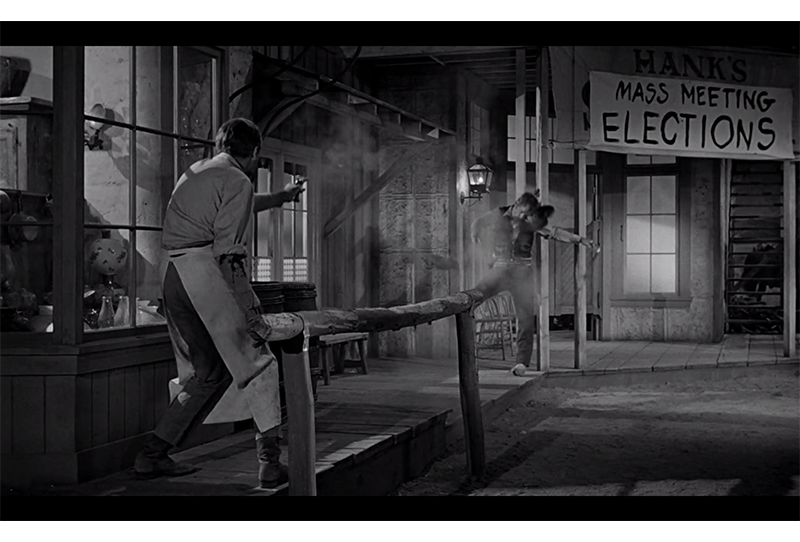

All these facts about Doniphon have been forgotten (except by two older residents, a cowardly one-time sheriff and Doniphon’s black sidekick), but there’s one more fact that Stoddard reveals, a sensational one that had never before been revealed publicly. Feeling guilty about his impending election being based mainly on having killed a man, Stoddard skulks out of the nomination convention. Outside, Doniphon confronts him and, in a flashback within the broader flashback, sets him straight. We see the same scene of the shooting, but from a different angle, from across the street. Doniphon, hidden in shadows, shoots Valance with a rifle just as Stoddard fires at Valance. “Cold-blooded murder,” Doniphon admits, “but I can live with it. Hallie’s happy.” Relieved of his guilt for having killed a man, a happy Stoddard returns to the convention and is elected; Doniphon, distraught at having lost Hallie to Stoddard (and perhaps conflicted for having willingly facilitated it), burns down his cabin in a drunken, tormented rage.

Stoddard seems relieved for having finally admitted the truth (the “fact”) publicly. (We know he has revealed it privately to Hallie, because just before telling the story, he had looked to her for a signal to go ahead, which she answered with a slight nod.) He assumes he has given the editor an incredible scoop. But the editor tears up his notes and announces he won’t print the story. Why not? Because, he says, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes a fact, print the legend.” The falsehood on which Stoddard’s stellar career was built will not be revealed to the public.

Except it has been revealed — not just to Hallie but to us. Director Ford has reversed the editor’s famous line. He has revealed the fact behind the legend. (He could even be said to have printed the fact, indelibly, as films in his day were indeed prints, on celluloid.) And the truth, as Ford sees it, is deeper and broader than this simple story.

That Ford’s film reveals the fact behind the legend suggests that he is ambivalent about the sentiment that the editor expressed and which most audiences assume Ford endorsed without reservation. Ford had exposed the fact behind a legend in an earlier film, Fort Apache, in which a bitter, vain, glory-hungry Army Colonel Owen Thursday (Henry Fonda) cynically but stupidly double-crosses an Apache band and leads his contingent of troops to annihilation, himself included. His wise but unheeded subordinate, Captain Kirby York (John Wayne), whom Thursday had banished to the rear (and thus safety) for a warning which Thursday interpreted as cowardice, does not reveal what really happened. Thursday is remembered as a great Army officer, a hero. And Ford’s The Searchers can be interpreted as (among other things) the rawest of facts behind the entire legend of the West.

But in neither of those two films did Ford invest as much subtle emotion in his characters as he did in Liberty Valance. In the flashback-told story, even though Stoddard is its narrator, Doniphon loves Hallie with more passion and generosity than Stoddard ever shows toward her. He expands his house for her. He saves Stoddard’s life for her. When he loses her, he burns down his house and presumably sinks into oblivion. By contrast, we might get the impression that had Stoddard lost Hallie to Doniphon, instead of the other way around, Stoddard would have shrugged, wished her well, got on with his law practice, and sent for a bride from the East.

The flashback-within-a-flashback, where Stoddard reveals the crucial fact enabling the legend, shows how deep Doniphon’s love for Hallie is. Doniphon doesn’t tell the truth to anyone except Stoddard. He tells him so that Stoddard will go back in the hall and accept the nomination — for Hallie. “You taught her how to read and write. Now go back in and give her something to read and write about.”

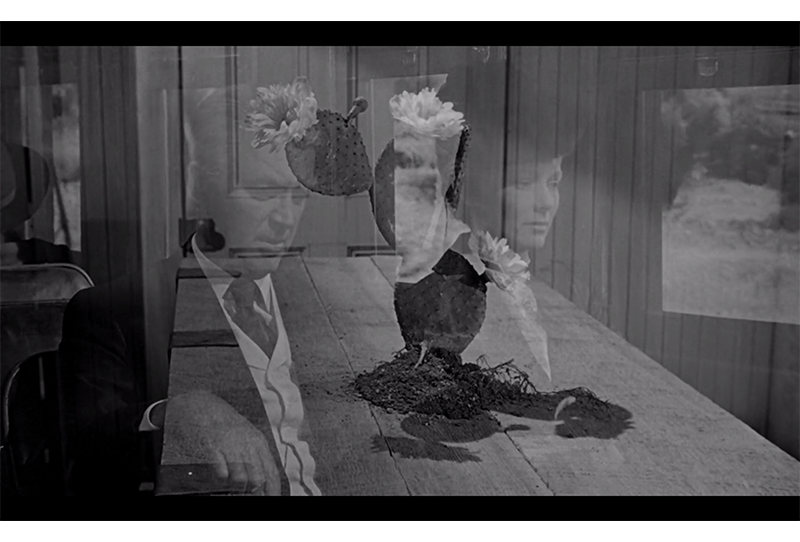

It is in its opening and closing sequences that the film reveals the complexity of emotions that the lie about who shot Liberty Valance eventually produced. The emotional meaning of the opening sequence, just after the Stoddards have arrived in Shinbone, is fully felt only at the end of the movie. Old Luke Appleyard (Andy Devine), the cowardly sheriff who remembers Hallie and Doniphon fondly, takes Hallie on a buggy ride to where he knows she wants to go. First-time viewers don’t know this at the time, but the destination is the site of the abandoned, burnt-out house that Doniphon had been fixing up for Hallie. She points to a cactus rose. Without being told, Appleyard digs it up for her. It’s a puzzling scene for a first-time viewer, because there’s no clue (except vaguely from the music) to what this is all about. On second viewing, you might want to cry.

Back in the undertaker’s establishment, Stoddard, having confessed the truth only to hear that it will not be revealed, and having a train to catch, starts to leave the room that holds the coffin but stops before closing the door. He has noticed that a cactus rose (prominent in the foreground of the shot) has been placed on top of Doniphon’s pine coffin. He is briefly taken aback. It’s logical to assume that he knows that Doniphon had once brought Hallie a cactus rose, to her great delight. Logical because that incident was in the story he told the reporters. And in that story, after Hallie exclaims how beautiful the plant is, Stoddard asks her if she’s ever seen a real rose.

In the film’s closing scene, Stoddard’s, Hallie’s, and Director Ford’s feeling about fact and legend surface. The scene begins as a dissolve from the previous scene. The cactus rose still sits prominently in the foreground, but now separating the emerging images of the elderly couple sitting side by side, looking straight ahead, not at each other, as they head back east on the train. Stoddard asks Hallie if, after he gets the new irrigation bill through, she’d be sorry if they just up and left Washington and came back to live in Shinbone. She brightens up, looks at him for the only time in this longish scene, and says, “Rance, if you knew how often I’ve dreamed of it. My roots are here. I guess my heart is here. Yes, let’s come back.” Then she looks out the window at the passing landscape, “It was once a wilderness, now it’s a garden. Aren’t you proud?” Instead of replying to that, Stoddard, in a tone of reproof, but looking straight ahead, not at her, pointedly asks her who put the cactus rose on Doniphon’s coffin. Also looking straight ahead, Hallie says, “I did.” After a full four seconds of the two silently staring straight ahead, the conductor comes by and tells Stoddard that an express train is being held for them up ahead so that they can get back to Washington faster. Stoddard somewhat pompously thanks him, then starts to light his pipe. The conductor says, “Think nothing of it. Nothing’s too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance!” That’s the last line in the movie. Startled, Stoddard can’t finish lighting his pipe. He and Hallie — who, remember, already knew the truth — just stare straight ahead. Stoddard looks miserable. His guilt at having killed a man (so he once had thought) has been replaced by guilt at having built a career on a mistaken public belief.

But Hallie is the key to the film and, I think, to Ford’s position re fact and legend as well as to considerations of masculinity. She loves Stoddard for his bravery in facing Valance — after all, he didn’t know at the time that Doniphon was covering for him — for introducing her to literacy, for her life as the wife of a distinguished politician, and for his accomplishments. But it’s hard to avoid the feeling that, in retrospect, she loves Doniphon, too. She has learned how much he loved her, what he did for her and Stoddard, what he gave up, and how much his loss of her hurt him. The tension in the last scene suggests it’s love she feels, not just gratitude. The emotions here and recalled are, visually at least, more intensively Dostoevskyan than in any film adaptation I’ve seen of a Dostoevsky novel.

Hallie loves both the simple cactus rose that Doniphon gave her and the sophisticated real rose that Stoddard gave her. We see little of the “real rose,” but we know all about it. It is the garden that Stoddard’s dams, roads, railroads, towns, irrigation, and barbed wire have made possible. In Stoddard’s mind, a real rose is far superior to a cactus rose. He as much as said so, putting down Doniphon (although not necessarily intentionally) in the saying. And he delivered it for Hallie. Does Hallie love one rose more than the other? Hard to say. She tells her husband he ought to be proud of the garden he has created, but her body language does not express the love for it that she showed to the cactus rose she placed on Doniphon’s coffin.

Ford’s position was pretty much like Hallie’s: conflicted. This is what makes him particularly interesting, unusual, and admirable. In this film and in others, he shows more personal affection and respect for the Tom Doniphons of his West than for the Ransom Stoddards. Men like Doniphon made men like Stoddard possible. At the same time, he seems to accept that the Ransom Stoddards represented progress which he felt was necessary for improving the country. Ford begrudgingly acknowledged that the kind of man he liked more was probably right to yield to the kind of man who would domesticate the West.

Had Ford lived to see our century, however, he might have had second thoughts. The masculinity that Doniphon represents, and which, for example, helped win World War II, is now widely regarded as toxic, as if there’s no distinction between Doniphon and Liberty Valance (who would have spent the war, and longer, in the U.S. Army Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, if not summarily shot). The country needs masculinity like Doniphon’s, and still has some of it: Todd Beamer, who gave the word “Let’s Roll” on Flight 93; Anthony Sadler, Spencer Stone, and Alek Skarlatos, who subdued the terrorist on a French train; Jonathan Smith, credited with helping save 30 lives at the recent Las Vegas shooting. But there seems to be an effort to discourage it. Today’s Army can’t find enough recruits fit for service. Pajama-clad, bespectacled, beta-male Pajama Boy, cuddling a cup of coffee, maybe tea, is the ideal of many. And the blessings of the real rose that the Ransom Stoddards ushered in are mixed; their dams, irrigation, farms, highways and so forth have produced a materially high standard of living, but they have also drained the aquifers, changed grassland into desert, converted rivers into trickles for dams that now are silting up, and transformed the natural wonders of the West into roadside spectacles. It’s nostalgic to yearn for the past, but it’s not nostalgic to think the cactus rose measures up pretty well to the “real” rose, and to miss it.

But why does it have to be one or the other? Ford posed the two types as before and after, the one coming before enabling the one coming after. But there’s no reason to doubt that those recent, real-life heroes were also gentlemen. Tom Doniphon was rough-edged, but gentlemanly — to all but Liberty Valance and his henchmen. Stoddard was inept but courageous. He would have rolled with Todd Beamer on Flight 93, rushed the terrorist on the French train, and helped save lives at Las Vegas — just not very effectively. Why can’t the virtues represented by Doniphon and Stoddard both be present in the same man? There’s a sense in which Ford’s typical paradigm — that rugged, outside-the-law men like Doniphon paved the way for gentle, courageous, civilizing men like Stoddard — is limited. There’s a third model of masculinity in Liberty Valance — Liberty Valance. It is this one that’s toxic, and much more like the ugly one revealed recently about celebrated legends — the rapists, the bullying harassers, the pedophiles. Ford totally rejected this model of masculinity.

Perhaps it’s time to distinguish between the quite different masculinities represented by Valance and Doniphon and acknowledge the value and potential complementarity of the masculinities of Doniphon and Stoddard. It appears both can inhabit the same man. Why not encourage that? •

Featured image by Isabella Akhtarshenas.