We had climbed halfway up the staircase of a Valparaiso sidewalk when Salvador Dalí appeared. He was stenciled to the landing above, waiting for us with his perked up handlebar mustache. For a closer look, my fiancée Melanie and I stepped around another stray dog, his long body blocking almost the whole width of the concrete step — Valparaiso’s take on multi-use public space.

Morning had barely arrived and cargo ships at the port, in the distance below, had probably unloaded enough plastic silverware to outfit Chile’s entire fast food industry. Meanwhile, the hung-over hills overlooking the port still slept, still hugged a blanket of overcast gauze. I wondered how many cans of Escudo beer the town had put back last night. And how many new stencils had been tattooed to its buildings?

Navigating the hillside topography of the city, we were hunting for said stencils and whatever layers of outdoor art we could discover. Decades of brush-stroke dialog — from political to phantasmal — have been blooming in a city that encourages murals as much as some other cities discourage them.

I felt oddly qualified for the undertaking. Thanks to having had just marked my 38th birthday, I had already been hosting a lively preoccupation with uncovering past layers of memories. I always find it remarkable how such an arbitrary date as a birthday has the power to unleash recollections, even when being 5,000 miles away from where I grew up in New England. Or perhaps it was not in spite of, but delivered by my Chilean surroundings: the wildly bright colors of the three-story houses stirring up the creations from marathon Lego-building sessions; or the city’s steps I hopped up like bleachers during springtime high-school track practice.

At the same time, I was beginning to see that getting lost in an alien landscape — we had just arrived in Valparaiso a few days before — can often lead the traveler to learn as much about oneself as about the surroundings. The uncertainty and newness of travel tends to shake the mind out of a groove well worn from repetition and comfort, melting off a congealed patina from atop one’s thoughts and memories.

Unlike previous birthdays, however, the flashbacks didn’t just show up and leave; they stung, vibrated, and loitered, to remind me of time passing. I was beginning to heed age and its wholesale irreversibility.

I found that the city’s murals offered a fortunate diversion from such matters. But I knew we would never find them all. Overlooking slanted steps as if to heckle pedestrians who slip on the abundance of dog turds, or hunkered down on trapezoidal spaces joining sidewalk and façade, the outdoor paintings of Valparaiso lie in wait, only revealing themselves footstep by footstep, wall by wall.

An exploratory, 20-minute stroll managed to yield such preliminary prizes as a spray-painted Pope Benedict XVI picketing with a GOD NOT DEAD (sic) sign; abstract funiculars inspired by the city’s creaky landmarks; stencils that refuse to forget the abuse during Augusto Pinochet’s 1973-1990 dictatorship, using a single red word PINOSHIT; giant eyes swimming in the confines of a threshold like a Steve Ditko comic book panel; yet another stenciled rat parachuting in. It was at once dizzying and engrossing. I was eavesdropping on many silent conversations at the same time.

Like the strays blocking doorways, the murals and spray-can designs were mostly ignored by fanny-packed tourists who skipped past them. Perhaps the paintings, relatively young when compared to the age of the buildings, marred the image of what a city quarter bearing 125-year old UNESCO World Heritage townhouses was supposed to look like.

But I found it difficult to separate the houses, hanging barnacle-like atop cliffs, from the artwork that accompanied them on the street. I noticed that as the rusted roofs and chipped trim spoke of a port that has seen more lucrative days decades ago, the paintings on the walls both announced the residents’ current visions while also recalling the elder city’s architecture and transportation methods, each era giving the other context.

What I soon realized about this street-level communication was what remained nearly absent: billboards and other advertisements. Before us, every inch of paint and dye — of both the houses’ riotously bright colors and the artwork — had been applied by hand. That could have been why even though few people walked around the hills in the morning, the streets felt human.

To an American like me who has had glossy, corporate-conglomerate ads railroaded into him since his youth (damn that Bubblicious jingle), I have expected that high-visibility walls become call girls for the highest bidder. Shouldn’t the landing of that staircase drip with mantras about the latest sneakers and how trendy and fulfilled you’ll feel when wearing them?

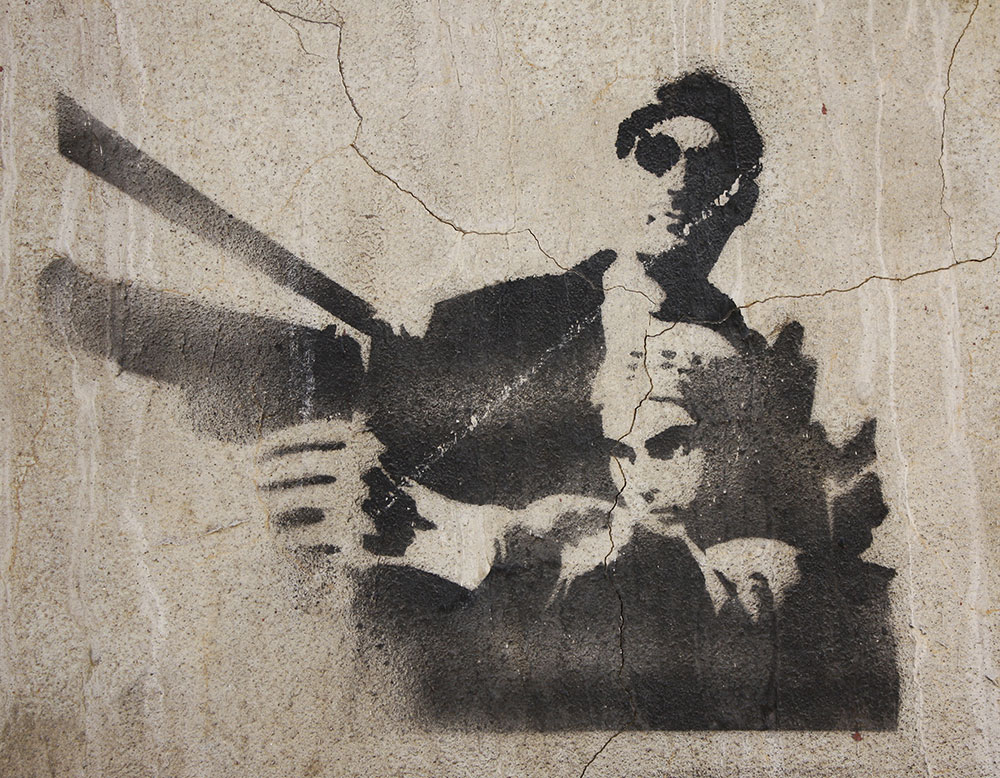

Instead, Valparaiso puts forth a much more even playing field of communication. The speculator’s battle cry of “whatever the market will bear” seems silenced when it comes to how a Valparaiso wall should be adorned. VALPARAISO IS NOT FOR SALE, shouted a stenciled hit on a zinc-walled house we just passed. British graffiti artist Banksy justifies his public art as a counterpoint to paid advertisements that one is forced to look at every day. As we climbed and descended the hills of the city, we noticed his multi-colored stencil style influencing the high-contrast Natalie-Portmans-with-sniper-rifles and the dancing Elvises hanging out on staircases.

Not that equality comes without its problems. The same fairness that allows anyone with presumed permission from a house’s owner to paint a mural is the same fairness that encourages anyone with a spray can to use the walls as a message board. Scrawled mantras — leftist, rightist, pro-homosexual, anti-yuppie — seem to breed overnight. The line between what is of cultural value and what is vandalism will always remain subjective, but judging from the unmistakable lushness of the city’s outdoor art, Chile deems the freedom worth the trouble it brings, since Chileans dealt with enough graffiti police under Pinochet.

In a way, however, the system tends to govern itself. Instances of narcissistic, tag-style graffiti — glorified names free of any purpose other than declaring “so-and-so wuz here”— rarely gain respect outside of the tagger and his few buddies, rarely last without being painted over, and rarely make it into photo books sold in the city’s art boutiques, as is the case with many of the more beloved stencils and murals. It’s an odd place for street art — the photo books both validating the art and stripping it of its environment — yet above all, the books reflect the reality that street art has become part of the fabric of the city.

I can easily understand such support for street art in a country that, in 2008, awarded government grants to jazz bands and indie comic book artists. Imagine one’s tax dollars funding a comic book featuring a character called Super Vaca, or Super Cow, who drives a garbage truck and battles a foe who looks suspiciously like Pinochet, and you’d be imagining what it means to be Chilean.

Art historian Rod Palmer, in his book Street Art Chile, found that the roots of the tradition dig down to former president Salvador Allende, who utilized political murals that eventually started a street art war with his opponent in the 1963 elections. (Allende is still celebrated in Valparaiso with his stenciled likeness.) When Pinochet seized control, his goons painted over the murals, both political and otherwise. In 1991, after his exit, street art began to reappear. As if to make up for lost time, two local painters teamed up with Valparaiso’s Catholic University to select a score of well-known artists, several of which having just returned from exile, to hit the retaining walls and houses of Bellavista Hill, a central knuckle poking from the city’s undulating landscape. Their pieces comprise what is known as the Museo a Cielo Abierto, or the Open Sky Museum.

Balancing ourselves on smooth cobblestones, our shoes groping futilely for level ground, Melanie and I entered a web of streets doubling as the Museo itself. Some of the artists, whose works hang in indoor galleries, preferred the indoor mindset, and painted perfectly rectangular pieces in the centers of irregular, terrain-dependent surfaces. Perhaps their message was to expand the idea of where traditional art can appear.

Meanwhile, the others worked the awkward shapes and bends into their designs, using the terrain as an inspiration rather than a limitation, the city itself becoming an artistic influence. Outside the streets of the museum, muralists used similar approaches. Images swallowed and digested drainpipes and doorways. One patch of sidewalk steps bordered a polygonal canvas framing ant-like cats dining on cigarettes, leading me to wonder what Dalí, whose mug appeared again down the street, would have thought of this offspring of his surrealism. Ghostly fatsos floated next to thresholds — telltale works of an itinerant Canadian artist known as Hecho, whose characters often appear in collages with local artists, such collaborations furthering Chile’s artistic cross-pollination.

On an inclined façade, we encountered a black and white mural, spanning a doorway, that I later recognized as the work of Fran & Frisura, a college-aged duo to whom Palmer devoted several pages, owing to their distinctive use of figures combining facial features of pre-Columbian art with robotic brains and innards. It was as if they were hacking time itself, warping the past with the future. In this particular piece, the duo responded to the irregular shape of the surface by painting a squat figure (a chessboard’s knight) on the shorter side of the space and a thinner character (a rook) on the taller end. Each of their murals could never exist anywhere else, even on another wall around the corner, without changing in some way.

I imagined what might happen if a mural had somehow been carefully removed from its perch on the street and hung in a museum. As you walk past the humorless museum guard, you place your hands behind your back and give a slight, obligatory nod while examining a flat, framed piece titled something like STREET ART STUDY, without its context of brick textures and shapes, without a faded Volkswagen carcass convalescing in front of it, without seagulls squawking overhead, without a dog turd slalom at your feet, and without the piston-pumping of your lungs from climbing twelve stories of sidewalk stairs to reach the piece.

There is an obvious advantage, however, to scoring an installation in an indoor gallery: longevity. On the street, free of enclosures that preserve the vibrancy of the paint, the murals lie exposed to the thirsty bleaching of the sun. And no security guards (humorless or otherwise) protect the murals from the whims of spray cans. A pungent example: when we neared the location of the Museo’s mural #3, painted by Eduardo Pérez (dean of the school of visual arts at Santiago’s Universidad Mayor), we first encountered a trio of high school-aged art students, crouched on a staircase landing, sketching the poetic geometry of the hills onto oversized pads propped up on their knees. When we discovered that a graffiti tag had recently destroyed Pérez’s mural that had been painted onto a surface a few steps from the students, the sound of pencils shuffling across paper stopped.

I turned to find their eyes on us. The one closest to us tucked his chin-length mop of hair behind his ear and said softly, “it was a beautiful work,” as if he felt obliged to apologize for the behavior of one of his countrymen.

However, 19 remaining open-air museum pieces are 19 more than were up under Pinochet, a dictator the United States helped to install in power. Maybe I should have been the one apologizing for some of my countrymen. With arcing gestures of pencils, the students guided us to some of the Museo’s other pieces nearby. The swishing percussion of sketching resumed.

Later, on an adjacent hill, I found myself staring at a mural of trompe l’oeil paper airplanes—complete with a hand throwing one of them — as I realized that two functioning windows, probably leading into someone’s living room, were at the center of the piece. Did the art become part of the wall, or did the wall become part of the art?

In the catacombs of a Valparaiso cathedral, Super Vaca just walked into a trap. He realized his misfortune when he encountered the remains of a mad doctor, a gurgling head in a bell jar, who asked to be turned to get a better view of the impending action. Too bad for Doc — no one paid attention to him and he missed the spectacle of his boss, the Supreme Commander, gobbling a pill that turned himself into an octopus with a head resembling a particular dictator from Chile’s recent past. With one of his tentacles, the Commander greedily seized Super Vaca and swung him around the cathedral. ¡Blamm! ¡Cromm! ¡Clanck! How will our hero escape from the suckers of a dictatorial cephalopod?

Chile’s peculiar stick-thin geography, racking up 4,000 miles of coastline rich in marine life, had fortified our hero with the experiences necessary to neutralize the threat. In the next panel, Super Vaca, like any self-respecting Chilean confronted with fresh seafood, took a bite out of the tentacle.

I’d decided to allow whatever apparent mid-life (two-fifths life?) crisis fermenting inside me to tire itself out, and that was when I finished reading Valparaiso artist Renzo Soto’s Super Vaca: Historias Negras on my birthday, finding a comic book perfect for channeling the past via the energy of escapist youth. After I had navigated the painted fantasy worlds on the walls of the city for the past several days, the story of a hero with horns of a bull and a talent for defending himself with his appetite appeared a little less impossible.

Most of the strays we encountered were either chewing on garbage or sitting on the streets like kings on thrones, taking visceral joy in forcing us bipeds to walk around them. But one moist-smelling specimen decided to follow us until it hopped ahead and began leading us up a staircase to a tight passageway awash in a crowded, boisterous congregation of murals. Even the staircase itself bore a painting of funiculars climbing and descending on the fronts of its steps, viewable only from the bottom landing, a reward for the skill of both artist and viewer. I tingled with satisfaction. We had found what seemed like a secret little pocket of the city.

With scratchy puffs of dog breath, the pug led us to a figure hunkered down near a hostel entrance, the young man’s curled frame leaning into a shoebox-sized Model-A roadster he was painting onto a stoop. He moved his brush in a slow, delicate stroke, as if to charm the image out of his mind and onto the concrete. At last, we caught one of the city’s elusive vandals in the act!

Like a host greeting guests in his living room, our criminal, his soft skin clinging to sharp cheekbones, offered us a gentle smile, the kind where the eyes smile too. He scratched the dog’s neck vigorously as he bent away from his creation to let us inspect his progress. His busy fingers kept releasing more of the ripeness of the pug, apparently not a stray after all. I complimented him on his dreamy take on a metallic subject and added, “Your dog brought us here.”

He answered, “He’s the hostel’s house pet.” The artist barely filled out his smock embroidered with the words HOSTAL BELLAVISTA; I found the same name spelled out in a tile mosaic under him. He told us that the Model-A was his latest offering to the hostel, as he had already completed several of the designs surrounding us on the passageway. Making beds, painting streets, cuddling pets — all in a day’s work in the Valparaiso hospitality industry.

The afternoon clouds burned up, allowing the sun’s rays to poke and finger the alleyways. Melanie and I leaned on a railing, staring down a crevice of a street where a slice of the port came into view. Her gentle insistence on taking a break had reminded me just how obsessive my mural hunting had become. Track practice was finally over. And thanks to our stillness, I began to view the hillsides as would the art students with sketchpads on their laps.

I could not deny the tug the city had on me. But I knew that not everyone could care for a place where, at that moment, somewhere else in the city, someone had taken a shortcut down the wrong pedestrian stairway and was being mugged. Somewhere on a metal rooftop, a stray dog was caught up in an indulgent snooze, stretched out impressively thin like spilled cake batter. Somewhere, an art student waited until a street was deserted and pulled out a cardboard stencil hidden inside her sketchpad.

The sunshine revealed the seams of the city’s layered eras — brick, corrugated zinc, rust, paint, retaining walls, more paint. The port was carrying its years proudly, especially considering that there are many ways a city can age. A city could simply decay into nothingness from neglect. Or it may be perpetually groomed in the same style, in an attempt to keep its appearance static, becoming its own travel advertisement that never needs updating, the Botox of urban preservation. Or it could be constantly converted into whatever scene the current wave of capital demands, a city that has no past. And then there’s Valparaiso, with its slowly settling foundations; its encroachment of feral fur in equilibrium with its rent-paying residents, keeping human development in an earthly perspective; its artwork that has been refreshing the city without replacing it, cultivating a traversable funicular of continuity that creates an intoxicating cocktail of eras and desires and dimensions. As I age, I hope to age like Valparaiso. •

All photos by the author