ML: Where does the name “Badass Cross Stitch” come from. Was it bestowed upon you or was it one that you adopted for yourself?

SD: Badass is one of my favorite words and I have this other project/website called “Seriously Badass Women.” And so badass just became this sort of brand or this word that people associated with me so when I started cross stitching, or launched the site, I was sort of like, “Well, I’m never going to do anything sweet or adorable.” There will be no puppies in my stitching so I was sort of like, let me help people understand what I’m trying to do here. And so that’s where that came from.

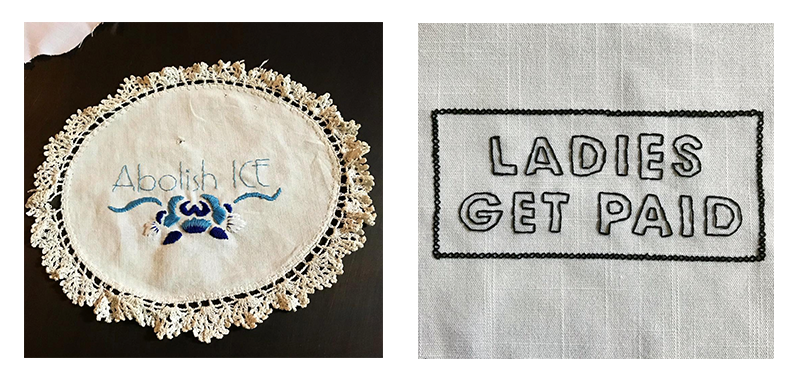

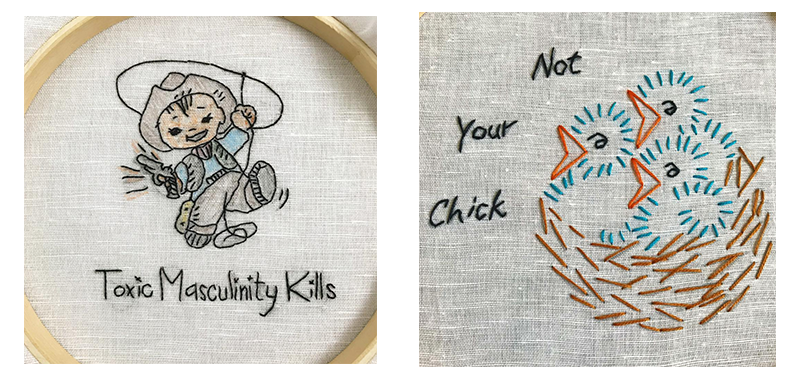

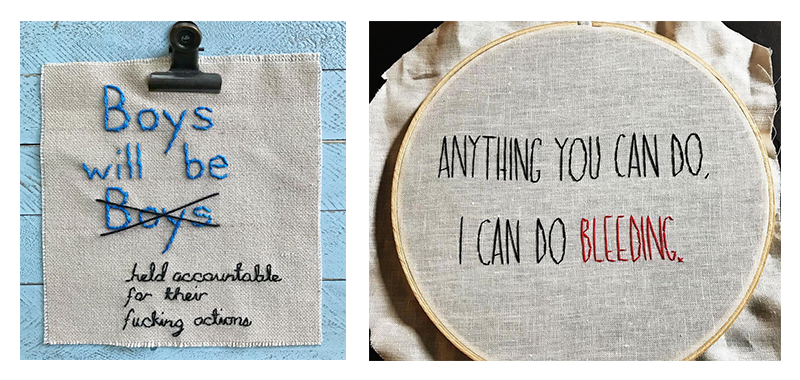

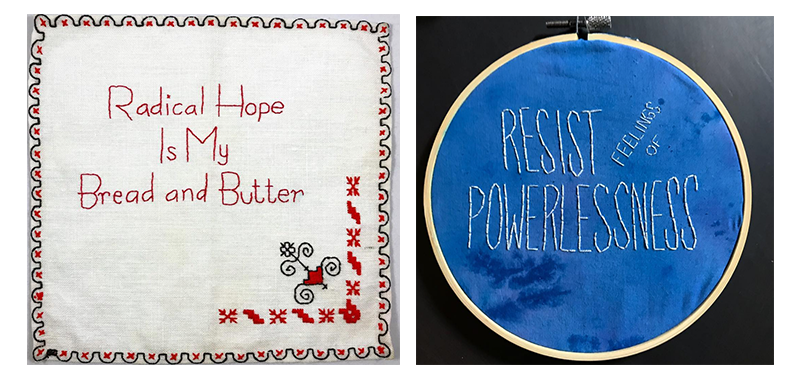

ML: I think one of the reasons why I like your work is that you’re exploding a lot of the binaries that exist: the delicacy of cross stitch with the hardness and aggressiveness of “fuck you.” The gentility with obscenity. I’m wondering how you kind of negotiate all these spaces because that’s always one of the difficult things with activism is “Am I being activist enough? Am I doing it?” And you’re also doing a lot of community building at the same time.

SD: I’m always thinking about how I can build community. How can I create space for people but in the same breath, I can’t be anyone else but me, right? But I don’t want to do it in such a way that it alienates people who could be within our community. It’s definitely going to alienate people who are in direct opposition to what I exist and stand for and I don’t care about them.

For me, are you on the edge? Could you come into the fold? If so, how do I work you into this and invite you into this. And I think a lot of times, folks align with a lot of the ideas but sometimes when there is this sort of hard line that people draw or this way of approaching a conversation as “this is right, that is wrong.” We can’t live that way anymore. Now it seems particularly important that we’re creating space and opportunity for conversation and dialogue and differing versions of opinions and thoughts around things and so for me, I’m super into that. I want to talk about all of the various ways of looking at a subject so long as it’s not directly in conflict with people’s basic humans rights.

ML: I used to teach gender studies classes in Northwest Ohio. And [talking identity politics] was always very difficult. But if you came at it hard, saying, “This is the way it is and this is how we’re gonna do it and I don’t care what you think. This is the way I think.” People always had a lot of trouble. But if you just kind of listened and said, “I understand that you work at or your parents worked at a glass factory for a long time and that must be really difficult but also maybe ask some of your neighbors who are not you how things were for them…” and then they would be receptive and open to doing that.

So is that how you also handle your invitation to participate?

SD: Yeah, everything’s an invitation for a conversation. I don’t actually believe that I have answers. Right? I have ideas. I look back at who I was 20 years ago and I look at that and I’m like, “I didn’t know anything.” And so I don’t want to assume that I know anything now, right? So for me, it’s about continuing to ask questions and continuing to absorb and listen and dialogue.

ML: Have you always embraced craftivism as a label?

SD: No, I didn’t even know that it was a thing for a long time. I was just starting out because I spent too much time on a computer and a device and I was burnt out and I had no creativity, so I started stitching to just do something analog. And then as a natural occurrence, how I think and live started to come out through the work that I was doing and I started to build opportunities for people to learn with me.

So the first thing I did was the year of stitch and each week I would teach myself a different embroidery stitch and then create a tutorial illustration and a photo illustration and show people how to use this stitch and I was like, “Learn with me. Let’s do this.”

And so that sort of opened the door to the community based projects and then a couple years ago, somebody called me a craftivist and I was like “That’s clever, what the hell is that? This is a thing?” And what I think is interesting about crafivism is the word’s only been around since 2003. It’s only gained real momentum in the last four or five years that I’ve seen. And I think it’s interesting to watch how different people connect to the word and the idea and define it.

ML: You said that there was a rise of craftivism in the past four or five years. Why do you think that is? Because I’ve definitely been seeing a lot more stuff in my feeds and circulating and I don’t know if it’s just the people that I’m hanging out with or if it just has exploded. But I’m guessing it’s more of an explosion.

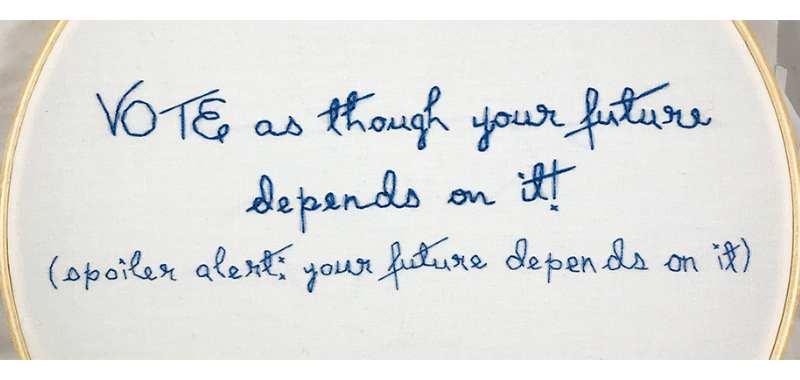

SD: I think it is. But I think Trump and the election, the Me Too Movement,and the success of the Pussyhat Project really opened the door for folks to say, “Yeah, I could do this too.” And this feels good. It feels good to make a statement or to do something.

One of the women last night was saying she made a Pussyhat because she didn’t feel comfortable going to the march or to a protest, so she made a whole bunch of them for other people to feel like there was a visual representation of her at that march, even though it was beyond her to be able to take that sort of action.

ML: Yeah. But I’m fascinated by the fact that there is a fabrics art community and how all these social media sites must make it easier but as you’ve said before, you know these folk but do not know these folk. So what is the fabrics art community like and is it easy to kind of get together?

SD: Real life together, not really. I think because of social media, we’re global, right? But we’re connecting with people all over the world; it’s lead to so many cool moments and opportunities to collaborate even though we’ve never met. So collaborating with the UK Nasty Women and just various folks all over. It’s not always easy to get together in person but there’s sort of this binding agent that leads to a lot of virtual collaboration and a real sense of community even though we might not be hanging out in person.

ML: Where is the most surprising place that someone has come to you and been like “This is really cool?” Have you had a “Oh, wow, I had no idea that somebody from here would be interested in my work?” How does it get that far?

SD: So when [Marielle Franco] was murdered, I did a piece on her and then everyone from South America was commenting, “oh, you’re one of my favorite accounts and I’m so grateful that you included her in this.” And I’m like, “what? I’m one of your favorites? What are you talking about? Who are you? This is amazing. And how did they get there?” So, I’m constantly impressed and astounded just by the geographic scope of things.

Yeah. Then when “Boys will be Boys” went viral, that too was shocking to see the celebrity pick it up and the result of when a celebrity picks something up.

ML: Yeah, I was gonna ask because that was something with Colin Hanks and George Takei, and I don’t know what you do with that or whether the urge is to just let it go viral or to amplify or what do you do with virality?

SD: Yeah, I just let that one go. It felt weird because it was this piece that I had made about Donald Trump but then it went viral in regards to Harvey Weinstein and I was just sort of like, “Why the fuck didn’t it get the attention that it should of gotten then? Because maybe we wouldn’t have this president.” Not that my piece was going to prevent that.

But it was just one of those like, “I wish people had felt this the way that I wanted them to with regard to Trump,” but now it’s being felt here, and then as it’s being used as the illustration for folks and their me too stories. It’s not even mine anymore, right? It’s everybody else’s but I feel like fiercely protective of it for them. When celebrities hook it on, what was interesting was when it first went out there, folks were using it but they didn’t link it back to me.

Which wasn’t the point. But it was also like, wait a minute, white men. This is how women get erased, right? You’re gonna not think twice and share this thing to say “I’m an ally.” But you’re not going to take the five seconds it takes to credit the person, the woman who made it. I started to raise a challenging point around how you don’t get to call yourself an ally and then erase the women behind all of this and then it lead to more interesting conversation and more interesting reach and expansion and then Vogue did a piece on it, because they were like, “Yeah, let’s talk about who made it and why.”

ML: I’m also sure that you get some virality the other way, not necessarily pro but also . . . Although I don’t know. I don’t see much happening your way, but I know there are a lot of other artists, like I follow, I don’t know if you know, Awards for Good Boys? She does these little ribbons. Like, “Thinks your leg hair is rad but could do without your mustache.” And these are the awards that she gives. “Makes eye contact with you when his phone is out of battery.” She always gets a lot of shit.

She also posts a lot of the things that people write in response to her stuff. And I don’t know if you get that same kind of backlash or if you have best practices that you have, whether that’s just ignore, address, or just whatever.

SD: I love block as an option. This is my space and this is my community and I will run it as I see fit. So for me, if you’re coming to my page and you’re commenting, and you just don’t agree with me and maybe sometimes are able to articulate that gracefully fine, we can have a dialogue about that.

But the vitriol and the misogyny and the threatening and all of that. No. There’s no space for that there and when I start to see people go after other folk who had positively commented and say awful things to them, nope. Block. Delete. Not a thing.

So the“Boys will be Boys” piece is on there and there’s like 30,000 comments or something. I don’t read them. I don’t want to read them. I do not care how anybody feels about that piece. They don’t matter. I don’t read the comments where I can’t control it. On Youtube, my comments are disabled because I don’t care. I don’t want to hear. You can talk to me in the ways that you can reach me, in a myriad of different ways if you want to have a conversation, but if you’re just trolling? There’s no space for you.

ML: I was also interested in how Chicago has been as a space for your work and how fabric arts have been operating there.

SD: Yeah, I love Chicago. It’s literally the best community on the planet and really anything I do, people are down to support. But that’s the spirit there. I’m from Boston and made my way down the east coast. Moved from Miami to Chicago to get my Masters. I’ve only been there only 12 years now. I started a business and ran it for ten years, a digital marketing company. And I would not have been able to start that anywhere else. Chicago has this spirit of “How can I help?”

In Boston, they would have been like, “What is wrong with you? Why do you want to do that? It’s never gonna work.” And in Chicago, they’re just like, “Yeah, cool. Of course you are. How can I help?” And that’s never wavered regardless of what I do. Like, “cool, I’m gonna shut that down and do advocacy work and embroider.” And they’re like, “Yeah, you should do that.”

ML: It seems we talked about the best of the internet, but it seems like Chicago is also the best of the Midwest.

SD: Totally biased, but yeah.

ML: What kind of projects are you doing now? You’re hopping all over cities.

SD: It’s interesting because I have a full time job, where I am the director of development for a nonprofit so I’m doing all of that and then I teach at Columbia College of Chicago and DePaul and then these projects are the rest of my time.

So Herstory was the one that I’ve been cooking up since last fall and building up to and launched it last week and already am just astounded by the response and the support and what’s happened with it. Like, the Design Museum of Atlanta incorporated it into their entire summer exhibit and had workshops before I even launched the project.

ML: What other projects are you excited about, either for yourself or others?

SD: I love the welcome blankets, which is, Jana, who is one of the co-founders of Pussy Hat, started this project called Welcome Blanket and it’s in full swing and it’s also part of the Atlanta exhibit this summer. Folks are making welcome blankets for refugees and immigrants who are coming into the country, which is a tradition that used to exist. They’re creating these blankets and writing them a welcome letter to the country and then giving them to immigrant refugees who are coming into the country, which, is there anything more traumatic than right now trying to immigrate to this country?

Or just trying to exist here, if you’re already here. So, I think it’s a really powerful project.

ML: Can we talk more about this Atlanta exhibit? Because it’s come up a couple of times and I would like everybody to know about it.

SD: So the Museum of Design in Atlanta, their summer exhibit is craftivism. And so Betsy Greer, who coined the term, I think helped facilitate the creation of it and it looks amazing on the Instagram.

They just opened June 2nd and they’re doing tons of workshops and the Herstory competent in the exhibit is interactive so you come, you stitch, and then you put your piece on the gallery wall and they’re changing them out as you go and then they’re going to mail them all to me at the end of the exhibit in September and then I’m flying down August 4th to do a workshop and to speak and hang out with folks.

ML: It’s just really interesting to me and I’m excited that there’s an institution somewhere, and I think in other places, that is recognizing the work of women crafting, understanding that it can be political as well as personal. Super feminism. I’m guessing that, I’m going to ask this anyway even though I think I know the answer, did you imagine when you started your first cross stitch that you would be invited to a museum in Atlanta to talk about your various intersections?

SD: That’s a hard no. Definitely not. Yeah, I mean, I think that’s how some of the best stuff happens. I think that’s how you can find your path. You just do what you love and what feels right and then if you’re doing it for the greater good, there’s no way that it’s not going to turn into something. I just had no idea what that would be.

ML: I think these paths opened up. It’s just what you said. And then you just followed them and it’s like, “oh, this happens all the time.” And I feel like that takes a long time to understand that you’re not in control and just allowing the process to happen. I hate to say that my mother was right, but she was right in a lot of those instances where she was like, “Just relax. Things happen and then you just follow what feels right at the time and then you figure out you were right and everything just kind of works out.”

And opens up all these exciting opportunities to do, it sounds like, everything that you’ve wanted to do.

SD: You just say yes. I mean really. None of these projects are mine, right? I just instigate and then I keep the momentum going. But to me, this isn’t my project. It’s everyone’s project. I’m just the person behind it who’s keeping it moving and making sure that people have what they need, right?

ML: Which is the ultimate feminist project. That’s what women have been doing for every political movement. Making sure shit happens. We have snacks and make sure that everybody is taken care of so we can all work together to break down bullshit.

SD: Totally, totally. So yeah, I don’t care about anything other than that everybody who wants to participate in this can and that they have what they need in order to feel successful at it and that in the end, because now I’m asking them to entrust me with these pieces that they have created, that the team that I put together to create the physical manifestation of this thing, honors their work and their trust in me and this idea in a way that they can be really proud of. And that is too big to ignore.

For me, this piece, this outcome, has to be so massive in scope that it cannot be ignored. Because it’s so often, the contributions are unseen, erased, ignored, and for me, the artifact of this has to be unignorable.

ML: Well, and I think that we have found how significant it is to get either a ton of voices or a ton of people in a space to demonstrate that it’s not just a meme, circulating around. That there are people who are coming together and saying this is something that we’re not okay with.

SD: Look at the voice and the diversity of voice.

ML: The fact that we are all coming together and being like “Yeah, we’re gonna hold some people accountable.” Which is exciting and to do this through cross stitch, which you’ve mentioned before is this medium that seems very insular, that’s associated with hyper-femininity but then when you put “fuck” or “bullshit” or “badass,” I think that it taps into a lot of people’s sensibilities. It’s something that both myself, my mom, and my grandmother can get behind in some way.

SD: Yeah, and that’s especially for this project that I want. And you’ll see that the tone of the Badass Herstory website versus Badass Cross Stitch website is very different. It’s still accessible and supportive and whatever, but on Badass Herstory, you’re not necessarily going to see my politics beyond feminism and social justice because I don’t want folks who are on the fringe in terms of political thingies, to not participate in this. This is for them. It’s for every woman, female-identified, and gender nonbinary human on the planet. And therefore, I want it to be something that everyone of all ages and all demographics will feel compelled to participate in, have their voice heard.

ML: It’s opt-in and also empowering in a way that is best for the individual kind of picking up the project, not these are my end goals. Welcome to the project.

SD: Yeah, it’s really just about displaying their stories and hearing their stories and giving their stories space and I care deeply that there’s sort of the individual component to it, where it’s like “I want you to spend time thinking about what your story is,” and sort of coming to a greater understanding of who you are and what shaped you and what matters to you, and then how do you put that out? How do you create that thing?

But then my hope is is that most people will create together, right? And that there will be some trust and community building through getting together to create in the same space together. And then hopefully, level three is that these communities and these moments move beyond just the project. I want you to then think okay, what can we do next? What can we do for our community? Can we mobilize? How do we evolve our civic engagement within this community and use the power and resources and trust that we’ve built in these spaces to do more?

ML: And I also imagine that this will foster identity across a lot of different subjectivities and provide opportunities for people to talk about standpoint, to do intergenerational, interracial, intergender, to bridge these gaps that are so often within activist organizations so segregated in of themselves to provide a project that multiple people can access which is very exciting and cool I think.

SD: To me, it’s the whole point. For me, that’s the point of this, right? The art is awesome, the digital catalog is cool, all of these things are necessary and amazing components to the project, but for me, the thing that matters is the communities that are being built and the conversations that are happening as a result.

ML: Yeah, it’s radical empathy. Which is one of my favorite things ever is to see the radicalization of love, conversation, empathy, like let’s get together. We can all find something that we want to destroy together, let’s do it.

SD: Yay!

All images by Shannon Downey. •