Art is remarkably popular these days. When I tell people that I am an academic working on the art market I often get an approving nod of the head that almost makes me feel like I am doing something meaningful with my life. But one also starts suspecting that the art market may be becoming a bit overexposed when you hear opinions on the merits or sale price of a Leonardo painting while having your hair cut. There are few other markets, except for those relating to technology, that has grown so spectacularly over the last decades – not simply in terms of the actual size of the market, but in cultural prominence. Art has entered the realm of the collective unconscious, exhibiting a cross-generational pull that bodes well for its future. It is not simply that the superrich are lavishing millions on paintings – it is also the increasing attendance at museums worldwide that is pointing to a thriving economic sector. The Louvre has broached the mark of 10 million visitors per year, New York museums are charging $25 per ticket, yet the constant flow of visitors is showing no sign of abating.

I had firsthand experience of that combination of cultural edginess and a trending market when I offered a course at a business school on Aesthetics and Art History. I intentionally avoided any reference to the art market in designing the course, promising nothing more than an overview of the history of art in ten sessions, emphasizing the principles of formal aesthetic analysis. The unexpectedly high enrollment, the enthusiastic response of the students and unusually strong work ethic throughout the trimester made me think that I have stumbled upon something deeper than just extended course offer and bored students craving excitement. Many of them were destined for careers in banking but were remarkably open to the opportunity of discussing visual representation. Experiencing a sense of forbidden pleasure for exposing future bankers to the history of art, I marveled at the relative ease with which brains attuned to complex calculations switched to the analysis of visual patterns. The combination of finance and art that unfurled before my eyes was truly intriguing, with their appearing as more compatible than even I had imagined.

This should not have been surprising – art and finance have a natural affinity and a long historical connection. Their affinity is based on similarities in the organization of markets and the nature of product evaluation in them. Evaluation is particularly difficult when involving unique, nonstandard products in fragmented markets, such as artworks or financial derivatives. The prices these fetch always depend on the perception of other market participants. In both art and financial markets, collective judgment looms large. Assembling an art collection is akin to financial investment in constituting a series of bets on what others would think as valuable and how the perception of it will evolve in the future. Value is formed on the basis not only of the formal properties of the artworks but also of the expectations and beliefs of others.

Another common characteristic of art and financial markets is opacity. Opaque are markets that are fragmented, lacking transparency over the distribution and pricing of assets. The lack of transparency in the art market is notorious, with dealer prices determined by practices that are inscrutable to buyers, based on information that is circulating within selective, tightly knit networks of gallerists and collectors.

The lack of transparency in the art market, the high degree of uncertainty about product quality and the resultant tendency for underinvestment in innovative, high-risk forms of art, are some of the key reasons for the historical pattern of the interweaving of art and finance. This connection goes back at least as far as the Medici, who created a vast system of artistic patronage, commissioning work from painters, sculptors, architects, and craftsmen. Colossal investment by banking families in Renaissance Florence contributed to the progressive reorientation of art toward humanism and technical mastery. As Michael Baxandall makes clear, artists were able to evade religious conventions by connecting directly with the sensuality, practicality and worldly eclecticism of their patrons.

This connection between art and finance resurfaced in the next centuries at regular intervals. The Golden Age of Dutch painting in the early 17th century is another example. The labor-intensive execution of the characteristic fine-grained style was made possible by the high demand for this art. As the research of John Michael Montias attests, this demand was primarily driven by upper-middle-class collectors with a strong taste for risk and novelty. Montias found that among buyers at art auctions merchants were the dominant occupational group, accounting for between a third and a half of all purchases. These merchants were active mostly in the international spice trade, characterized by the unpredictability of supply, the uncertainty of price fluctuations and high risk of shipwrecks. Critically, these were not plain merchants, but “investors”, seizing opportunities within a broad range of activities, including financial transactions. Their taste for risk, exoticism, and novelty oriented them toward products with uncertain economic value, such as spices, tulips and paintings.

This kind of “investor” accompanied the emergence of other genres in the history of art, with the proverbial example of Modern art in the early 20th century. The art-collecting syndicate “the Bear-Skin Company” was formed in Paris in 1904 with the objective of supporting the work of young artists and encouraging new styles. The reference to la Fontaine’s fable about two hunters selling the skin of a bear before trying to catch it (and ultimately failing) conveyed the understanding of the members of the high risk of their investment strategy. The syndicate pooled money from 14 members to purchase works by emerging artists, to be sold at auction a decade later. Most of its members were bankers, well versed in the language of investment and accustomed to estimating the odds of long-term performance. The success of the venture was instrumental in enhancing the credibility of Modern art, as it demonstrated that this art was not only valuable as an investment but that it also offered an opportunity to collectors to affirm their taste in making selections among the thousands of paintings on offer.

The art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler is a pivotal figure in the history of Modern art. His activity was fundamental in securing a degree of financial stability to young artists, such as Picasso and Braque. His background was in banking, having started his career at a bank in Frankfurt. When he moved to Paris he knew much better how a bank operates than a gallery. He applied his knowledge of financial markets in developing a long-term strategy that allowed him to transform the avant-garde artworks that attracted his attention into marketable objects. Among his clients were the Russian collectors Shchukin and Morosov, who amassed outstanding collections of avant-garde paintings, undeterred by the public derision that many of these provoked. Their profile was similar to that of the 17th-century Dutch buyers. Merchants by occupation, they invested in a broad range of activities, including factories, insurance companies, and banks. Their collections were the first to put emerging artists on an equal footing with established names, making them commensurate and allowing viewers to juxtapose styles and establish connections. This was instrumental in reconciling the accepted and avant-garde art forms, encouraging conservative buyers to start considering more seriously the work of experimental artists.

The emergence of new styles inevitably creates uncertainty in the evaluation process. But as these historical observations attest, such situations attract collectors accustomed to the uncertainty of investing and predisposed to making speculative bets. The involvement of these collectors-investors was a force of change, as it imparted credibility to new, experimental art and contributed to the erosion of established hierarchies by encouraging the spillover of aesthetic value between genres or periods within collections.

The rapprochement between art and finance becomes conspicuous again toward the end of the 20th century. As a source of insight, I used data gathered by “ART news” on the leading 200 collectors for each year in the period 1990–2015. These data provide information on the profile of the top collectors in the art market. 782 collectors were featured in the database, with half of them based in the United States and most of the rest in Europe. Unsurprisingly, the most preferred genre for collecting is contemporary art, followed by Modern art and Old Masters. The growth of contemporary art is simply spectacular. If in the early 1990s a bit more than half of all collectors were active in contemporary art, this share has risen to 90% by 2015. The fact that 9 out of 10 top collectors are buying contemporary art speaks eloquently to its attractiveness and to the intensity of competition for artworks of quality.

By far the most intriguing finding was on the economic activity of the collectors. The increase in the proportion of collectors involved in the financial sector or active as investors is striking. From a bit more than 10% in the early 1990s to slightly below 40% by 2015, the collector with financial-investment profile has come to dominate the ranks of the leading art collectors. The nearly four-fold increase attests to an important shift at the high end of the art market, featuring the rising prominence and clout of hedge-fund managers, bankers and investors. While customary to hear statements that the art market is entering a qualitatively new era, these results imply that it may be more appropriate to say that we are returning to a bygone era. Remarkably, about the same proportion of top collectors nowadays (40%) have an investor profile as was the case in early 17th century Amsterdam.

There are other reasons for the growth of the art market, particularly that for contemporary art, but the role of these investors should not be underestimated. Investors are naturally attracted to those market sectors where value is most uncertain and fluctuations are most significant. The “conceptual” nature of the art that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s created a favorable ground for the involvement of collectors with a conception of value as something uncertain and shaped by shifting collective sentiments. These collectors were naturally attracted by the immaterial and abstract works of art with no underlying, objective value. Contemporary art was becoming increasingly dematerialized and defined by the way it called attention to its own process of transforming objects and spaces into art. The growing presence of this new type of collector both reflected and reinforced the salience of art that flaunted its conceptual nature, ambiguity, and openness to interpretation. It appealed to investors with its directness, accessibility, and eclecticism, and with the opportunity to create value in a similar manner to that in the stock market.

This point has hardly been made more eloquently than in the film Wallstreet, where abstract, contemporary paintings serve as a background for Gordon Gekko’s musings on the nature of capitalism and the power of money to transform or translate things into marketable objects. Oliver Stone managed to encapsulate a very complex social and economic process in a single sentence: “money is transferred from one perception to another, like magic.” Explaining the financial market by alluding to contemporary art was original and foresighted, as it fleshed out the increasingly perceptual nature of both financial and art markets. This was the common ground that facilitated the rapprochement between these sectors, reflected in the growing presence of investors as collectors, donors or members of museum boards, or in the growth of bank art collections. Reducing this process to “speculation” and the pursuit of financial gain, as is often the case in the mass media and in a casual talk at artistic venues, is shortsighted. Many investors saw the art world for what it was increasingly becoming – an extension of the world they lived in, embodying similar principles of evaluation and pricing, and governed by similar mechanisms of information control and social exclusion.

Wallstreet was released in 1987, but it presaged the acceleration of the alignment between art and finance that originated in New York in the late 1980s. This process is epitomized by the vertiginous rise to stardom of Jeff Koons, who became the darling of an art market that was increasingly pertinent to the financial universe. His own involvement in the financial sector and command of the language made him uniquely positioned to produce art that encoded this language to perfection. The interweaving of art and finance triggered a booming market that would culminate decades later with the stratospheric auction prices we are witnessing today. Art that defied categorical boundaries and that increasingly divested itself of technical exigencies and formal constraints were naturally appealing to collectors with a strong taste for diversity, flexible aesthetic preferences and a high tolerance for risk.

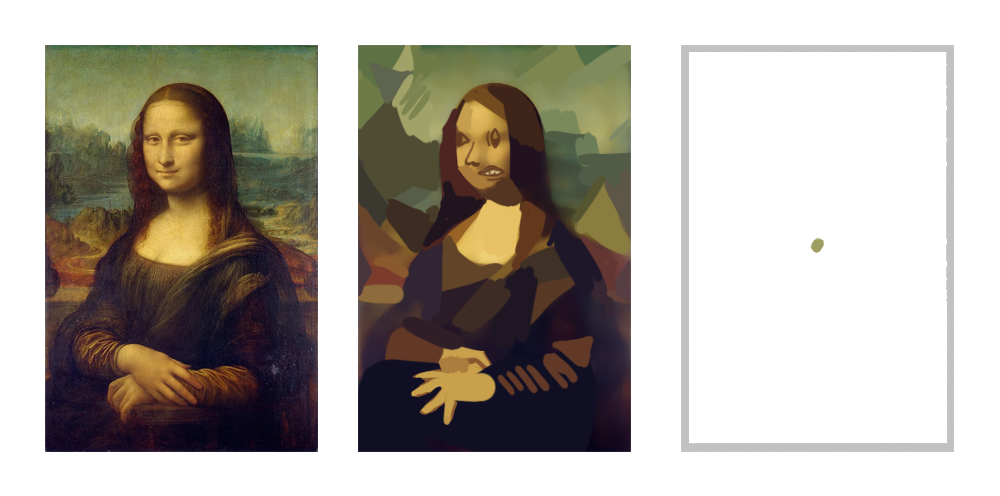

This alignment between supply and demand, between the profile of collectors and the nature of art, is a key reason for the observed tendency of art to become more expensive and eclectic. What was increasingly valued in both investment and art were not focus – on a particular style or business activity, but the lack of focus. Eclecticism in collecting or business creates possibilities for interaction and for the occurrence of spillovers between genres and economic sectors. But this logic of eclecticism is naturally at odds with the principles of evaluation used in critical judgment. Expertise is resolutely categorical in nature, based on a set of conventions that discourage transgressions and spillover across categories. The inevitable conflict of logic would have but one winner. In the course of the 20th century, the discussion in the aesthetic realm progressively shifted from How is it made? to What it represents? Intention prevailed over execution, art became more and more conceptual and hybrid, reflecting the innate capacity of money to abolish boundaries when given free rein.

Market forces are inherently democratic in the sense that they tend to reduce contrasts between categories. When expressed solely in terms of money, the difference between an Old Master painting and an installation becomes one of degree, not of aesthetic content or technique. Conceptual, ambiguous art is democratic when it permits avoiding the discussion of technique and quality, putting different types of art on an equal footing, erasing boundaries and lumping together distinct principles of evaluation. One is left befuddled by the ease with which boundaries are nowadays crossed and evaluation principles juggled. As the recent scandal with the self-destructing Banksy painting suggested, the art market of today is starting to resemble a hybrid creature from Greek mythology, defined by the metamorphosis of objects and value. No clear lines exist in this world between material and conceptual work, between the act of creation and that of destruction, as the material morphs into conceptual and as destruction morphs into creation. The process of destruction appears to hold more interest now than that of production, which tends to fade into the background. One barely needs to look any further than the record sale of a visibly flawed painting by Leonardo (and his workshop), to illustrate how technical aspects are dwarfed by the power of the brand.

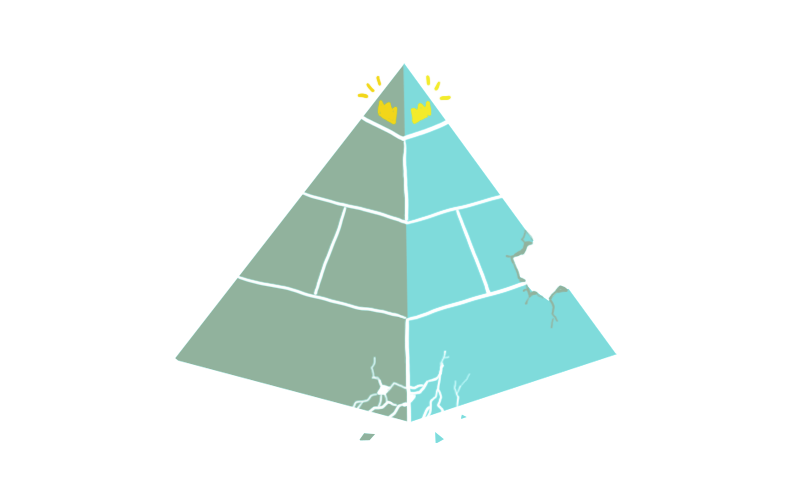

The breathtaking speed at which records are falling in the art market reflects the confluence of complex socio-economic processes, such as increasing inequality, the concentration of wealth and excess liquidity, but also the growing share of the financial sector in the economy and skyrocketing remuneration of its top executives. Simply put, those willing to invest in expensive art have more disposable income than ever before. From the early 1980s, the share of the financial sector in the U.S. economy is steadily growing. But an even more precipitous increase is observed in its rate of remuneration. After declining for decades after the Great Depression, relative wages in the financial sector have started a steep increase since 1980. As excess revenue generated in the financial sector flowed into art, the art market boomed. The growth of the market is welcome news, as it creates demand and employment in an economic sector that is not immune to economic cycles. At the same time, the infusion of capital led to the bifurcation of the market reflected in the concentration of revenue at the high end. Tellingly, fewer than one-quarter of one percent of artworks sold at auction last year garnered one-third of total sales. The mean is increasing, but the top segment is increasing much faster than the rest of the market.

What this signifies is that the art market is benefitting from structural shifts in the economy, but that its cohesion is decreasing, as it increasingly resembles industries, such as professional sports, marked by huge income discrepancies, superstardom and strong brand power. The benefits of a thriving market are obvious, but the downsides are visible too. The rising inequality is skewing the distribution of power. The huge resources that can be mobilized in support of star artists can lead to deformations in evaluation, as a reflection of an “oligarchy of taste”, constituted of affluent collectors, mega galleries and superstar artists, confronting a public increasingly disconnected from the opportunity to influence the consecration process. Other risks include the vulnerability to changes in tax legislation that may lead to the outflow of capital or to economic and political shifts that result in the dramatic contraction of the financial sector.

The connection between art and finance is historical in nature and complex in form. Investors had a pivotal role to play in key developments in the history of art. With their tolerance for risk and penchant for eclecticism, investors contributed to the credibility and success of a number of artistic genres, such as Modern and Contemporary art. The combination of a thriving financial sector and art that proved highly malleable in aesthetic terms was the driving force behind record-breaking tendencies in the art market of today. However, it also contributed to the decoupling of expertise from evaluation, excessive hybridity and the importation of a highly skewed pattern of inequality from other industries. There is little doubt that the last few decades have substantiated the prophecy of Gekko that “the illusion has become real.” We can only hope that the real would not turn out to be an illusion if and when the music stops playing. •

Images illustrated by Barbara Chernyavsky.