TSS: Let me start by asking about one of the many Roman oddities: for people that were so concerned with their genealogy — so obsessed, as you point out, that they would put great effort to fabricate it back to the founders of Rome and mythic kings — they seemed remarkably willing to accept outsiders as Romans and as emperors and as consuls.

MB: In a way, those two things aren’t quite as contradictory as they might seem at first sight, because the point is that if you follow those genealogies back to whether the men came with Aeneas from Troy or the first citizens of Romulus, those people, too, were outsiders. And I think Rome is rather adept at somehow managing to find a way in which everybody is an outsider. It think it’s quite nice to think of somebody like Catiline. Catiline is actually from one of those very, very old Roman families, and he looks as absolutely Roman as you can get. That’s one of the paradoxes about his clash with Cicero, who is rather a new man and kind of new money. Well, where does Catiline’s family really come from? Actually, they came over from Troy with Aeneas. So the joke is not whether some people were native and others weren’t; it’s at exactly what point were you foreign? Because everybody is foreign somehow.

TSS: I’m tempted to make a political analogy with immigration and Europe and the United States now, but instead I’m going to focus on the fact that you mentioned Catiline and note that the anniversary of the speech that you open your book with just happened — what, November 8th? And I was wondering why you picked the “Quo usque” speech as the opening of your book. What makes it such a significant moment in Roman history that out of a thousand years to choose from, you picked that speech?

MB: Well, I think there are two reasons, really. One is the incident as a whole, rather than just that one speech, is a place where we really know a lot about what was going on. We can tell the story of Rome day-by-day in ways that actually you can’t do again for centuries. It is perhaps the richest moment in Roman history, and so it’s a good place to take people to as a kick-off. It’s somewhere where people can really get their teeth into the material in a way that I think is quite surprising to people who have not read much about Roman history.

Read It

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard.

But I think it’s also an incident where it is very hard not to see how there are resonances and echoes between our concerns and the Romans’. I think that the story is quite a simple one: that Cicero, a leading elected official in the states, believes that he has uncovered a terrorist plot that’s going to overthrow the government, eliminate the leading men, and actually destroy the city of Rome from top to bottom. In the speech with which I start — a speech which still survives — he goes to the senate, the main counsel of the state, and he denounces the leading conspirator: the terrorist Catiline, who, fairly shortly after Cicero’s speech, decides to call it a day and leave town. Cicero then decides that he has to round up Catiline’s terrorist associates, which he does, and, using the rather vague and unsatisfactory term of a “homeland security act,” he kills the conspirators without trial. He has a very chilling moment in which he is overseeing their execution and he just says one word: “Vixere.” They have lived. Meaning: they’re dead, and they live no longer.

To start with, all of this looks like a triumph to Cicero, but very soon it turns sour because one of the most fundamental principles of Roman citizenship and of Roman liberty was that any citizen, on no matter what charge, had the right to a free and fair trial. Very shortly he is sent into exile — not for a very long time, he returns after a few months, but he is never as powerful again. And while he is in exile, his house in the center of Rome is demolished and a shrine of a goddess of liberty is put up on its site.

Now, telling the story in that way, and I think that’s a reasonable and fair way to tell it, you instantly see that you’ve got the Romans here, dealing with one issue that we find almost impossible to manage: how far is it legitimate to override the citizen rights of an individual in the interests of homeland security and protecting the state as a whole? It takes very little to see that the issues of Cicero and Catiline are replayed in Guantanamo Bay, in British attempts to increase the length of time a citizen can be held without trial. We’re there dealing with just that problem, and I think that the example of Cicero and Catiline shows how imponderable, difficult, and constantly-debated an issue that must be.

TSS: When I went to high school, I was forced to memorize the “Quo usque” speech as part of my Latin history class, where we translated the account of Caesar and the letters of Cicero and we tried to write our final paper on what date Caesar’s army crossed the Rubicon. It was probably the most rewarding high school class I ever had, and when I spoke to the people in my office who are significantly younger than me, not a single one had even had high school Latin. Your book begins with the sentence, “Rome is important.” Is something being lost that people aren’t getting this education that I was perhaps the last generation to receive?

MB: I think something is lost, but before we’re too gloomy about that, I think people get an education in classics in many different ways, and in many different areas, and in many different stages of their education. I’m somebody who thinks it is an extremely good idea if people have the opportunity to learn Latin in high school. But I think that there are really wonderful classes in Greek and Roman civilization at college and university which are allowing people to reconnect at that point. I’m not totally gloomy; I just think that pattern of where people pick up Latin or classical civilization has changed. I don’t think we’ve become a classic-less culture, but I think that there are all kinds of reasons for making sure that we do not become a classics-less culture.

Cicero and Catiline don’t tell us how to answer our problems, but they give us a framework for thinking about it in a very stark and powerful way. I think there are all kinds of areas of Roman culture where you can see similar political issues being framed by Roman writers and by Roman historical example. The lurid stories we tell and enjoy about transgressive Roman emperors are actually quite important politically in thinking about the very nature of autocratic power. We might sort of thrill rather to the idea of Tiberius having his genitals tickled in the swimming pool by little boys, but one of the things we’re thinking about when we tell those stories is about the excesses of autocratic power that we will not put up with.

The other obvious reason is that anybody who walks out their front door in the West is constantly walking into a world that is itself or has over the last two, three, four hundred years itself engaged with Roman culture, whether that’s the way we think about slavery when we watch the movie Spartacus, or that the columns that adorn the fronts of so many museums tell us about some way in which our own culture is always looking back to some bit of the antique world, or that when we read Dante we can’t also avoid thinking about Virgil. So I think there’s a way in which Roman culture is very much embedded at the heart of what the West talks about when it talks about culture. Now, Western culture’s got all sorts of other influences — thank heavens we’re not just some sort of rather dumb heirs of the Romans — but Roman ideas of what it was to be a person, what it was to be a citizen, what it was to understand art, what it was to think about display, autocracy, and what it was to value literature are very much embedded in our own culture.

TSS: Now, another one of your themes, in addition to what we should know about Rome, is what we can’t know about ancient Rome. So, for example, Cicero keeps coming up again and again in your book. How much of our view of a thousand years of history is influenced by one man with a very, as you show, biased viewpoint at any given moment? How does that reflect on the broader issue of what we can and can’t know?

MB: Look, I’m all for myth busting. If you look at the Roman world, I think it’s quite liberating to be honest about some of the things that we can’t ever know about it. Apart from Cicero, we can’t really tell the life story of any other individual person. We can tell bits of their life story, but not a biography. Cicero so dominates the story of the end of the republic that it’s very hard to see what the other side of the argument looked like. I think it’s quite helpful always to remind people of that. When I did Catiline at school, I think that nobody did suggest to me that Cicero was anything other but heroic; it was terribly mean that he got exiled.

I think there are two sides to the question of what we don’t know about Rome, because the other side is we know so much more about things than we think we did. If you were to say to somebody, “Did you know that so much Roman literature survived that you could not possibly get through it all intelligently in a lifetime?” they would be amazed. Saying “We don’t know about some things” is perhaps suggesting we might be better to ask slightly different questions because there are an awful lot of things that we do know that we maybe don’t notice because we’re so concerned with other issues.

If you were to try to summarize to people what the range of Roman literature surviving was, you would go from everything from science fiction, basically, to pornography, to history, to legal discussions and legal theorizing, philosophy, medical writing, fortune-telling, joke books. It is so terribly surprising that so much of it has managed to get through two thousand years to us, and I think it’s something to celebrate.

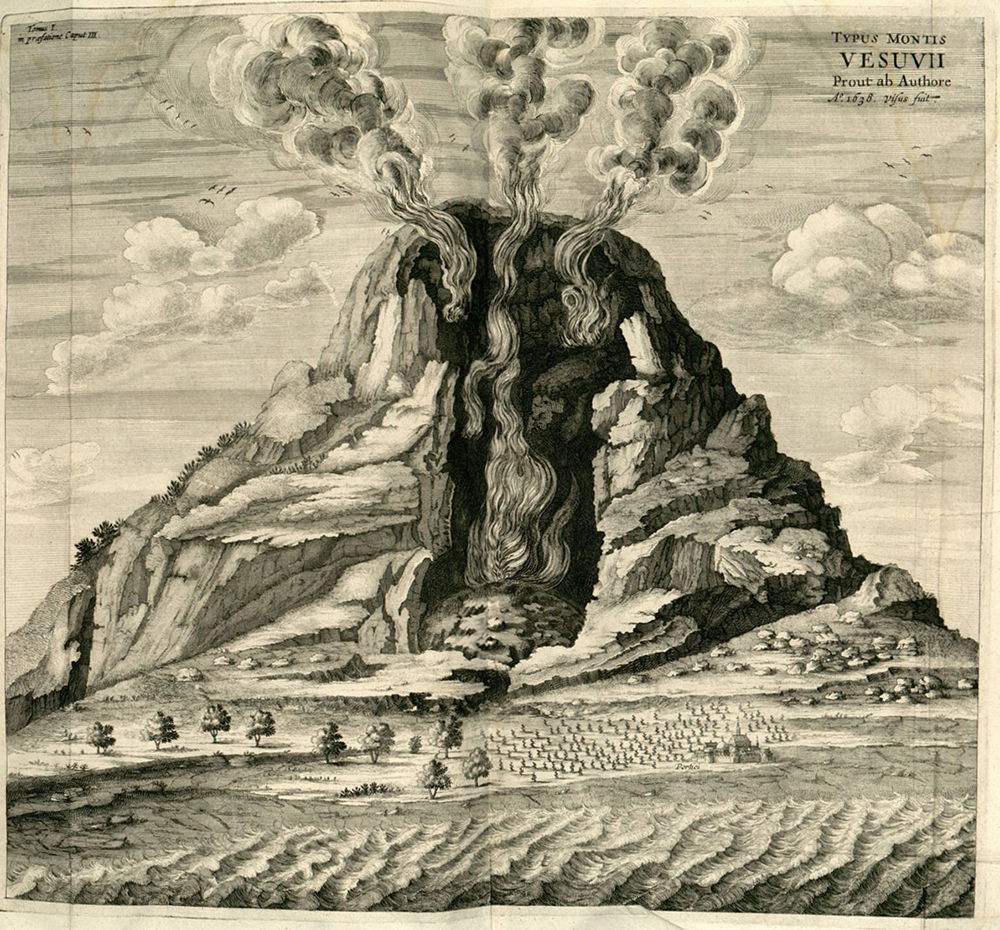

TSS: I read your book on Vesuvius, and I think somewhere in there you say that one of the things that was interesting was that the poor people ate out while the rich people were able to cook at home. And then I saw a documentary on BBC, and they said that they had done some recent DNA tests, and, because of seasonings, they discovered the poor were cooking as well. Is this a disagreement or an advancement?

MB: I think it’s something of a disagreement, and also it depends a bit on what you mean by cooking. Let’s imagine an ordinary, poorish Roman. It is not inconceivable they have a bit of a brazier at home and they cook up things from time-to-time. It was very high fire risk, difficult, and dangerous, but, I’m sure, a bit of cooking went on in the home. On the other hand, what I was trying to point out was that this was an interesting case where Rome was completely topsy-turvy for us. We assume that the restaurant is the privilege of the rich. And yet, in Pompeii, for example, you’re not looking at major cooking at home by the poor: there’s not the space. That isn’t to say that they didn’t occasionally — I’m using this metaphorically — brew up a cup of tea on a brazier.

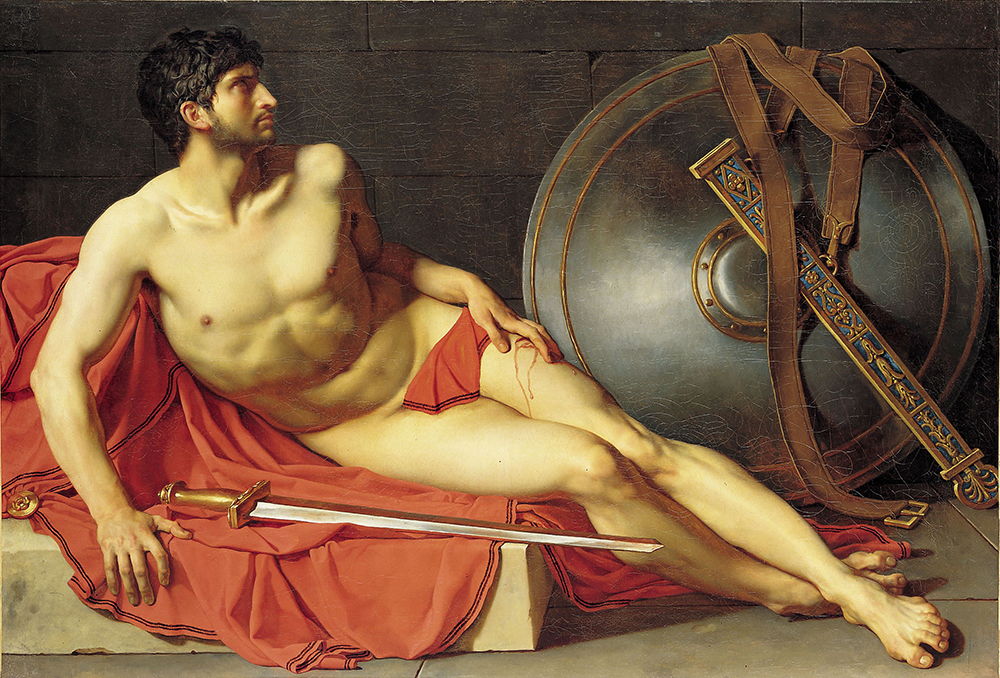

TSS: That reminds me of another thing I didn’t know until I read your book, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. Another way the Romans were different than us is that originally when the legions were set up, the poorest of the poor didn’t have to serve, whereas in our culture it’s usually the rich who sort of buy or maneuver their way out of service.

MB: Yes. It’s very interesting: the absolute assertion of privilege going with the responsibility to fight for the state. It’s something that modern culture certainly overturned. The whole world of military service and the army within modern culture has, we would say, become professionalized, but I think it’s actually let the rich off the hook, by and large.

TSS: In Rome the rich weren’t trying to avoid it. They were trying to lead armies into battle.

MB: Exactly. And that’s why they’re very different: the privilege went hand-in-hand with military responsibility, rather than went hand-in-hand with the evasion of it. What does a Roman dream of? A rich Roman? Well, he might dream about being consul, he might dream about building a vast villa, but most of all he dreams about military success. So, you find someone like Cicero, who, in all kinds of ways, is the most un-military guy of all — he doesn’t have a clue about anything to do with soldiery — he gets out to his province in Cilicia, he leads his rather small number of troops in some rather minor skirmish against some local bandits, and instantly you find him talking about himself as if he was Alexander the Great. Cicero is a great example, as is the old emperor Claudius, who, for all his old, doddery, very unsexy image, what does he does he do when he becomes emperor? He invades Britain and he has a Triumph.

TSS: And you mention in your book, on the Triumph, that it was sort of a pathetic attempt to get him a Triumph — maybe not the entire invasion, but it was a factor.

MB: Yes, because he’s a guy where the one thing you know about him is he had no military experience whatsoever. Roman emperors were priests, they were orators, they were benefactors, and they were generals. You’ve got to be a general in part. You put it very strongly, but I agree with you, I think, that it’s an absolutely essential part of the makeup of a Roman leader identity that we have lost. It could be for the better, you know, but we have lost it.

TSS: It’s not just that a number of them also died in battle. Even ones like Cicero that didn’t die in battle, who died in relation to the state, you almost wonder: why would anyone want to be a successful Roman consul? Their death rate is extraordinary!

MB: It is extraordinary, isn’t it? They’re looking back to Romulus and Remus and they are fantasizing about civil war being written into their genes, but, my goodness me, they have a hell of a lot of it. We probably have a skewed version of this because the period we know best in Rome is the period of the biggest violent internal conflicts and upheavals, and it might not have been the same in the third century B.C. On the other hand, my hunch is that it wasn’t that different. It’s a culture in which violence and force is ultimately the bottom line of dispute resolution, whether that’s dispute resolution between city and the outside world or dispute resolution inside the city.

TSS: And this is during a period when they’ve developed a very sophisticated level of philosophy building on the Greeks, I mean Nero had Seneca, you had Marcus Aurelius, yet none of this seemed to lead them towards any sort of questioning of the military.

MB: My old teacher Moses Finley used to say that what you have to remember about the ancient world — both Greek and Roman — is that war was the default position. It wasn’t war that broke out; it was peace that broke out occasionally.

TSS: And yet you go to great lengths to show that the Romans at least felt the need to claim that each war they were forced into, not by their own aggression, but by something done to them, some need to bring peace.

MB: One of the very, very biggest questions about Roman expansion and Roman militarism is how you understand ultimately what’s driving it. You can see the culture across the Mediterranean — it’s not only the Romans that are, in our terms, mind-bogglingly militaristic. But what actually is making Rome go to war so consistently? One can be extremely cynical about their claims to find just wars, and one thing that you have to respond to that is that there are not many cultures in the world who don’t claim to fight just wars.

TSS: Fair enough. In your book, you tried to reclaim interest in the Etruscans and argue that they were actually the more powerful community in the early days of Rome.

MB: Yes, I’m sure that’s true. And in fact, I think it’d be wrong to say that they were the more powerful community; I think it’d be better to say that some Etruscan cities were much more powerful than Rome. There’s a bit of a danger about taking the Etruscans as a kind of block, but yes.

TSS: So you had the Greeks, this incredibly sophisticated culture, you had the Etruscans, you had various others — Why the Romans? Why did they become the empire?

MB: I think you have to be very careful about lumping these cultures together. The Greeks, very occasionally, did think of themselves as Greeks; similarly the Etruscans. But you have a series of cities who are effectively independent, and I think we shouldn’t make the error of imagining that Athens was somehow typical of the Greek world any more than Tarquinia was typical of Etruria.

That said: Why did the Romans win? Ultimately, it is something to do with their consistent incorporation of their defeated enemies into the Roman project. A crude stereotype, though a not entirely wrong one, of standard inter-state warfare in the ancient world was that City A bashes up City B, takes them prisoners, takes them slaves, demands indemnity, and says goodbye. Now, what Rome does is overturn that sense that the enemy just walks away in the end with its loot. Because what Rome does is walks away with its loot, but it also, in the process, forms a permanent relationship with the people it has defeated, whether one of alliance or one of citizenship. And the obligation that goes with citizenship and alliance is to fight for the state of Rome. What that means is that Rome gets an enormous reserve of manpower — way bigger than any of these others can put on the field. Probably we’re talking about 700,000 men available to Rome, and that’s what gives it victory.

TSS: To leave the Roman Empire for a second: for a classics professor, for any professor, you’re very engaged in the public sphere, including little things like Twitter. I’m wondering if that was a conscious decision, something you fell into, a way you feel the classics need to be represented, or just something you want to do.

MB: I don’t think it was a conscious decision. It’s a bit like the Roman Empire, isn’t it? A series of decisions get taken, and in retrospect you can see that they were facing in the same direction, but you didn’t realize it at the time. I think I’ve always felt that there was something of an obligation on people whom the state paid to study a certain culture that was dead 2000 years, to be an active citizen. One repays the state’s investment in one’s research by doing one’s job as a classicist and by being an active participant in this thing.

TSS: Since we’re in an election season here and just finished one in your country, I was wondering if we could talk about the Roman election process a little.

MB: Well, in some ways it looks appallingly familiar to our own. I don’t know if you know the wonderful little treatise supposedly written by Cicero’s brother, Quintus. It’s called Handbook of Electioneering, and it’s always a great favorite of classically trained British politicians because it has bits of advice in it, which look so like a rather cynical spin doctor of the early 21st century. It’s almost too good to be true, like: “Promise anything because you won’t actually have to deliver it,” or “Always shake everybody’s hands.” “Try not to make enemies.” “It doesn’t really matter if you’re promising entirely inconsistent things.” I remember I had a great encounter once with Boris Johnson, mayor of London and an MP and classicist, who read some of these bits out with immense glee.

I think there are some engaging and very superficial similarities, but I think also we would be unbelievably amazed by the time-consuming ritualism of a Roman election. One thing that’s very interesting about the Romans — one thing they failed to get right — is that they do start to become the closest thing in the ancient classical world to a nation state, but they never adjust their central political institutions in a way that takes account of their growing size. So they have an electoral system, which demanded everybody turning up on the same day in the forum or whatever when they have citizens who are far-flung by several hundred miles, and that’s only when you’re thinking about Italy. When you look at our system, and there are all kinds of things one wants to criticize about it, it in some ways beats it. If it’s quite broken, it’s not half as broken as the Roman one was by the first century B.C.

TSS: Let me ask you just a kind of whimsical question. If you could move the people politely and dig down and explore one place, where would be the best place in the world where you could find more answers?

MB: Now that’s a very interesting question — Where would you like to dig? Blimey. I’m extremely interested in the penumbra of buildings just outside a city. One thing that has interested me, both in terms of Pompeii and in terms of Rome itself, is just how far we should really import a third world model into these cities. We’ve got a million people living in Rome. Now, you can pack them all into the city. You can put them in high-rise buildings, you can have a very high density of occupation, and you can just about get a million in. It’s always struck me that one of the ways of understanding how these cities work would be, actually, you have squatter camps outside. These are of course very, very difficult to trace, archaeologically, because they’re going to be tents, they’re going to be little huts, they’re going to be like the City of the Dead in Cairo. I just wonder if that’s true. And I’d like to know.

TSS: By the way, are you going to write a second part of your book, or are you leaving it at 212 C.E.?

MB: I’ve got two things on the go. I am writing a book based on some lecture I did in Washington, D.C. on images of Roman emperors in later art. How did Roman emperors get portrayed in Renaissance and, later, painting and tapestry and silverware? Connected to that, but more specifically ancient, I shall be writing a book which looks harder at Roman emperors and tries to find a way to exploit some of these anecdotes about imperial vice and occasionally virtue, and to wonder what the historical significance of them is beyond the question of whether they’re all true or not. Can we shelve the idea that Caligula actually slept with his sisters and that Domitian really did pull the legs off flies? And can we think why those stories are told? Or what they tell us about Rome? Or what they tell us about us?

TSS: You mean Caligula got a bum rap — that maybe there was some logic to him insulting the senate, what may be more bad leadership than insanity?

MB: I think, ultimately, we’re never going to know. The investment by the Claudian regime in completely dumping on him is so great we can never see through it. To some extent, I don’t think that revisionist attempts to kind of rescue Caligula are any good, except that I think it’s worth reflecting how they might go. I mean, it’s a bit like “What would Catiline’s side of the story be?” Once you try to read it against the grain, I think you do get a more nuanced picture of what might be going on, but I think you do have to avoid leaping into the “My goodness, me, Caligula was really a very hardworking man who was terribly misunderstood.” I rather doubt that’s true. •

Lead image: Mary Beard by and © Robin Cormack. Other images by Freud via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), Eugenio Hansen via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), Thomas Hawk via Flickr (Creative Commons), Athanasius Kircher via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), Jean-Germain Drouais via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), Andrei Nacu via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons), mateoutah via Flickr (Creative Commons), Bert Kaufmann via Flickr (Creative Commons)