Home alone one night, I pored over my Brontë shelf: beautiful editions of the novels, an assortment of biographies, the complete letters, and various books on Brontë lore –– of which fans all over the world never seem to tire. I soon reached for one book in particular: an edition of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights together that my father had given me for Christmas when I was 14 years old. It’s bound in plush red leather with gold writing on the cover and gold-edged pages. Opening it, I read the inscription:

To Kristin,

for her 14th Christmas

Read with delight and pleasure, my dear.

Love, forever and

ever,

Dad 1983

Tears sprang to my eyes, for my father had recently died. Seeing his handwriting again and his lovely inscription was like getting a little “hello” from him when I least expected it — and when I most certainly needed it. I was alone in the house because my husband was out of town at our sister-in-law’s funeral. She had passed away just three weeks after my mother died, which happened nine months after my father died, and my husband’s father had died five months before that. It had been a brutal stretch of time, and on this rainy October night, reflecting on our losses, I turned to my books for solace and distraction — and, upon seeing my father’s inscription, for remembrance.

I read Jane Eyre in that volume shortly after he gave it to me, but it would be another ten years before I’d read Wuthering Heights, in a graduate course on the novels of the Brontë sisters, which sparked my Brontë mania. My mother shared my delight and pleasure in the Brontës, and we enjoyed talking about their lives and works. Of the countless things I miss about my parents, exchanging and discussing books with them might be what I miss the most.

I found myself combing through my books on another night, pulling this and that from the shelves to refresh my mind on storylines, look at beautiful dustjacket art, and inhale the aroma of crisp new pages or musty old ones. I came across another book from my parents — and then another, each carrying an inscription from one or the other or both of them. Soon, I had a stack in my arms and headed to my laptop to type the inscriptions out. The books were birthday or Christmas presents spanning my entire life. Some I had read several times, others not even once.

I decided at that moment to read, or reread, all of these books. Not necessarily in the order in which I received them; instead, I would let the process unfold organically and reach for them as the mood struck for a particular author, genre, or theme. I would try not to have any expectations and just enjoy the reading experience. I would head down any rabbit holes that opened up for exploration. And I would consider how the books intertwined with one another, for as Virginia Woolf says in A Room of One’s Own, “books continue each other, in spite of our habit of judging them separately.” They reflect, respond to, and resonate with each other across time and space, heedless of the boundaries often imposed by academia and the marketplace. In their infinite variety, they make room for readers everywhere, inviting us to consider what it means to be human in a complex world.

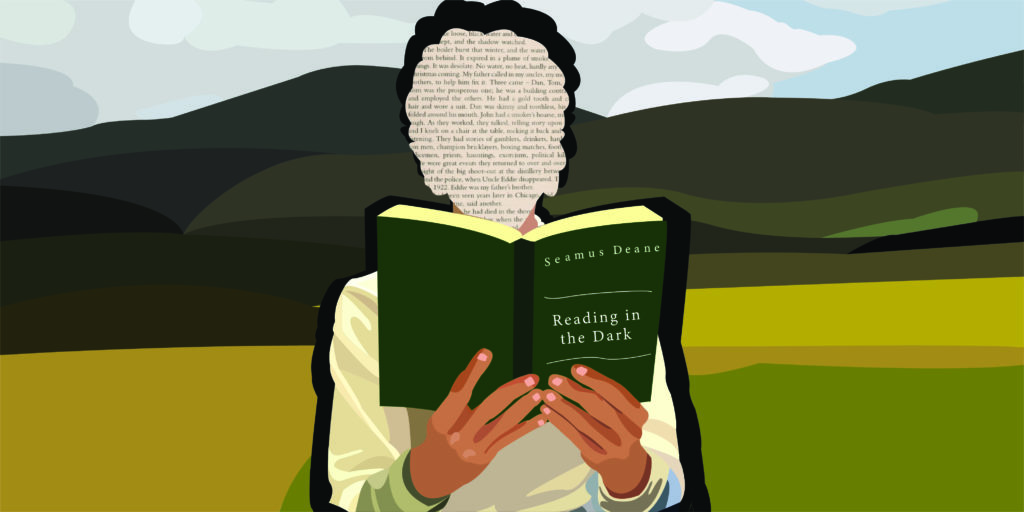

My parents gave me the gifts of life and literature. Delving into the books from them might also, I thought, offer a means of communing with them once again. I also wanted to reflect on who I was when they gave me each book: a child of 12, a teenager, an adult turning 25, then 35, then 50 years old in the blink of an eye. A nostalgic enterprise, to be sure, yet one that would enrich my life in the present and perhaps light a way forward as well. I began with Shel Silverstein’s A Light in the Attic and Dylan Thomas’s A Child’s Christmas in Wales. The third one I read was Reading in the Dark, by Seamus Deane.

•

To Kristin

from Mom

Christmas 1997

I can think of several reasons why my mother might have given me Reading in the Dark. Seamus Deane was a professor at the University of Notre Dame, where I had gone to college and where my father was also a professor. I had recently taken a Joyce seminar in graduate school and became enamored with Irish literature. And the novel had received glowing reviews. I remember reading it in bed, my husband beside me, in our last apartment in Chicago. Picking it up recently, I recalled only a rough outline: an Irish Catholic boy’s coming of age amid strife in Northern Ireland. And I remembered it had haunted me. I finished reading it on the night of January 6, 2021, hours after United States citizens stormed the Capitol in protest of the presidential election results. Appalling images of the frenzied mob filled our screens. I felt overwhelmed by shock, anger, and sorrow. A few times that night, I turned away from the TV, picked up my book, and slipped into the besieged territory of another time and place.

In Reading in the Dark, the unnamed narrator tells of growing up in Derry, Northern Ireland, his childhood marred by the history and present-day of the Troubles. Spanning 1945-1961, with a brief final scene set in 1971, the novel contains chapters comprised of vignettes whose titles create a disturbing narrative of their own: “Accident,” “Pistol,” “Fire,” “Blood,” “The Feud,” “Field of the Disappeared,” and so on. Ghosts haunt the narrator’s home — or so his mother seems to believe. An old slaughterhouse and the ruins of a whiskey distillery blown up by the British provide the backdrop for his and his friends’ neighborhood wanderings. Secrets fester, for men on both sides of the family have a long history with the Irish Republican Army. When the narrator, at around eight years of age, throws a rock at a police car to distract a bully about to assault him, the repercussions are far more grievous than he had ever anticipated.

The narrator leavens such grimness by describing excursions into the countryside — with its sea air and the cry of gulls, its caves and rock formations from time immemorial, its folklore and folk heroes. As always, however, human conflict implicates the landscape, as in a vignette called “Grianan” — the Giant’s Causeway, “a great stone ring with flights of worn steps on the inside leading to a parapet that overlooked the countryside in one direction and the coastal sands of the lough in the other.” Inside was a “wishing chair of slabbed stone. You sat there and closed your eyes and wished for what you wanted most, while you listened for the breathing of the sleeping warriors of the legendary Fianna who lay below,” the narrator says.

One hot summer afternoon, on a rare holiday, the narrator’s father takes him and his brother Liam to an outcropping known as the Field of the Disappeared, where “the souls of all those from the area who had disappeared or had never had a Christian burial . . . collected three or four times a year . . . to cry like birds and look down on the fields where they had been born. Any human who entered the field would suffer the same fate; and any who heard their cries on those days should cross themselves and pray out loud to drown out the sound.” The narrator wonders whether this was where the restless soul of his Uncle Eddie, his father’s brother, came to mourn his lost patrimony. Although he doesn’t ask, he senses much more that his father isn’t telling him. Years later, he realizes his father had been trying to convey to him the location’s significance in the chain of events concerning Eddie’s demise.

•

Before I knew better, which took an embarrassingly long time, I viewed Ireland in the superficial light of a picture postcard. I imagined green fields, rocky shores, fluffy sheep, and beautiful woolens. Ireland possesses all of these things, but I was wholly ignorant of the reality on the ground. As a child, my awareness of Ireland began and ended with Mary Mast, née Faul, my mother’s best friend, and a second mother to me, who lived across the street. Our two families had children about the same ages, and we all grew up together. Mary was from Louth Village, about an hour north of Dublin by the coast and several miles south of the border with Northern Ireland. Cecilia (Cece) and her twin, Brian, were the same age as my brother, three years older than I, but she and I were close friends throughout grade school especially.

I remember the packages her mother’s sisters, Auntie Bid and Auntie Eleanor, would send from Ireland, full of comic books, candies, and Lucky Bags: treats wrapped in newspaper and colored tissue. I especially loved the Smarties, equivalent to our M&Ms. I remember when the aunts would visit and stay for a few weeks, times when the Mast house rang with laughter and Irish accents, enchanting to my ears. And I remember my mother telling me about a time she was over at Mary’s when her sisters were visiting, the four of them talking, laughing, and, in a sign of the times, smoking cigarettes late into the night. At some point, my mother mentioned “Londonderry,” and the three Faul women became incensed. “It’s Derry!” they exclaimed as my mother sheepishly apologized. This was my introduction to Irish political fervor. That and watching the video of U2’s live performance of “Sunday Bloody Sunday” hundreds of times on MTV.

The song’s title referred to the day Irish civilians had been killed by British police. Like millions of other young people at the time, I found the video enthralling: the song’s powerful drumbeat, Bono’s strutting around the stage, the crowd’s roars and cheers. “Sunday Bloody Sunday” came across as a principled stand against injustice — but at 13 years old, I didn’t know what, exactly, principles, stands, or injustices were. As Harry Browne writes in his book on Bono,

Bloody Sunday can refer to two events in Irish history: a date during the War of Independence of 1920 when the IRA killed British intelligence officers across Dublin, and soldiers retaliated by shooting into a Gaelic-football crowd in Croke Parke, killing fourteen spectators; or an afternoon in 1972 when British paratroopers again killed fourteen unarmed civilians, this time after a civil rights march in Derry, Northern Ireland.

With Ireland on my mind, I sent Cece a message mentioning the (London)Derry story and that Reading in the Dark had prompted the memory. She wrote back about her uncle, Denis Faul, a priest, and prominent civil rights activist who was instrumental in ending the 1981 hunger strikes undertaken by Irish political prisoners. “Because my Uncle Denis was so embroiled in the Troubles up north,” Cece wrote, “we were not permitted to discuss it nor were we encouraged to read about it.” He was a controversial figure, “as outspoken against the IRA as he was the British,” she said. I Googled his name and learned that in addition to his role in ending the hunger strikes, he also “campaigned for the release of the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four and the McGuire Seven before their causes became well-known and vindicated.” He co-authored numerous books, such as H Blocks: British Jail for Irish Political Prisoners and The Hooded Men: British Torture in Ireland, August, October, 1971. “He stared down the barrel of many a British and IRA rifle,” Cece wrote.

I was fascinated by his story. I remembered meeting him once when he was visiting Mary and her family. I told my mother afterward that he didn’t look me in the eye when we were introduced and that I found that very strange. “I’m not surprised,” she said. “Priests rarely deign to look girls or women in the eye,” a comment rooted in her many years of feminist activism. Cece added Reading in the Dark to her reading list, and I asked if she had read Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by Patrick Radden Keefe, which I knew of through book reviews but hadn’t yet read. She said it was on her nightstand and that she remembers as a child hearing about the kidnapping of widowed mother of ten, Jean McConville, the event at the center of Say Nothing from which Keefe’s history of the Troubles unspools.

•

In the 1980s, when I was in high school, rumors circulated that Notre Dame professors were funneling money and arms to the IRA. Where would I have heard such a thing? And which professors? Ours was a Notre Dame neighborhood, the campus less than a mile away. Most of the families up and down the street and for blocks in every direction had one or both parents on the faculty. I never asked about these rumors, spoken in hushed, anxious voices — but I could have. A political science professor, my father would have welcomed such questions, but I wouldn’t have known how to begin. I had no frame of reference, although I vividly recall watching my father watch a story on the news one night about the Troubles. He stood in front of the television with a frown on his face. For people like Mary Mast, the fear was palpable. “My mom was terrified through most of the ‘70s and ‘80s,” Cece wrote, “so, in typical Irish fashion, she repressed it.”

Cece also told me that the title Say Nothing comes from Seamus Heaney’s poem “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing” — and Heaney’s title quotes a poster that appeared in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, showing an armed, uniformed IRA paramilitary in a balaclava and bearing a message comprised of collaged bits of magazine and newspaper print: “Loose-lips cost lives In taxis On the phone In clubs and bars At football matches At home with friends Anywhere Whatever you say — say nothing.” Paramilitaries deployed the injunction to “say nothing” as a threat, a means of instilling fear and enforcing silence in their ranks. They meted out fierce discipline to those suspected of “loose lips.” In April 2016, the Irish News reported that the posters had reappeared on the International Wall in west Belfast. The news story also mentions Heaney’s four-part poem.

•

“Whatever You Say, Say Nothing” begins with the speaker “writing just after an encounter / With an English journalist in search of ‘views / On the Irish thing’” — the word “thing” characteristic of the press’s downplaying of the strife and dehumanization of the Irish. The “jottings and analyses” of the “media-men” are rife with bias and clichés and serve only to exacerbate the discord and violence, the speaker states. He calls out English politicians and journalists for disregarding Irish suffering and for demanding the internment of IRA activists despite the atrocities perpetrated by the British and the unionists. The betrayals and blasted landscapes of Northern Ireland rise up in Heaney’s poem like a hydra. “This morning from a dewy motorway / I saw the new camp for the internees,” the speaker states. “A bomb had left a crater of fresh clay / In the roadside, and over in the trees / Machine-gun posts defined a real stockade.”

While the entire poem resonates with Reading in the Dark, Part III most strongly evokes the experiences of the novel’s narrator. “‘Religion’s never mentioned here,’ of course,” the section begins, evoking the hypocrisies, prejudices, and double-talk of factions in the North. “‘You know them by their eyes,’ and hold your tongue. / ‘One side’s bad as the other,’ never worse”—this last comment a supposedly neutral one that disgusts the poem’s speaker: “Christ, it’s near time that some small leak was sprung / In the great dykes the Dutchman made / To dam the dangerous tide that followed Seamus.” Further harming the Irish living in the North is the unwritten rule among them that “to be saved you only must save face / And whatever you say, you say nothing.” Children were warned never to divulge information about themselves lest they be pegged as Catholic or Protestant, and harmed. “Smoke-signals are loud-mouthed compared with us,” Heaney writes. Yet by remaining silent, the Irish become complicit in their own oppression in a “land of password, handgrip, wink and nod, / Of open minds as open as a trap, / Where tongues lie coiled, as under flames lie wicks, / Where half of us, as in a wooden horse / Were cabin’d and confined like wily Greeks, / Besieged within the siege, whispering morse.”

The directive to say nothing permeates Reading in the Dark. The narrator relates the many conversations overheard throughout the years between his father and uncles about what happened in the 1920s — to Uncle Eddie and to Aunt Katie’s husband in particular. Nothing is certain, however, as aspects of the story alternately coalesce or clash with each other. Family lore carries the ring of truth, but the chaos of one night in particular, along with his parents’ repression of the trauma, places key details forever out of reach. “A choice, an election, was to be made,” the narrator decides, “between what actually happened and what I imagined, what I had heard, what I kept hearing” about the night his father’s older brother, Eddie, met his fate. Details are jumbled. “Maybe I had imagined and should try to forget it,” he says of “a story about one of the IRA men in the distillery strapping himself to an upright iron girder at the corner of the building as it caught fire.”

Similar uncertainty involves the gun Eddie carried that night —

a First World War rifle that had belonged to a Black-and-Tan soldier killed in the War of Independence . . . Was it Dan who had said this? Or Katie? Or Grandfather? I didn’t know. I could hear all their voices in the kitchen but I couldn’t match a voice to a detail . . . Much of it must have been ornament, people making strange little alliances in their heads between things they had heard or read about, seeking to assert themselves in those endless conversations, implying they were in the know, there was much else they could tell, but . . .

he trails off. Such is the subjective, piecemeal nature of memory.

His grandfather’s deathbed confession to his daughter (the narrator’s mother) only worsens the trauma. As the narrator gradually pieces together the truth, he imagines a conversation he might have with his mother in which they both divulge their long-held secrets. He despairs of any such resolution, however, for there remain too many unknowns. “And how did I know I had been told the truth?” he wonders. “Shouldn’t I just ask her? What did you know, Mother, when you married my father? Why did you silence me, over and over?” Ultimately, he too chooses silence in the hopes of protecting his mother and especially his father even though it means driving a wedge between them. “Staying loyal to my mother made me disloyal to my father,” he says. “In case I should ever be tempted to tell him all I knew, I stayed at arm’s length from him and saw him notice but could say nothing to explain.” Yet in contemplating his father deeply, he develops deep compassion for him — perhaps more so than if there had been no secrets at all.

•

Reading in the Dark makes for an intense reading experience that prompted a constellation of memories and reflections. Because of this novel, I reached out to one of my oldest and dearest friends, evoking those long-ago years when our families were so deeply interlaced. Cece’s revelations of the Troubles’ presence in her childhood home provided insights into her family and the resilience of parents who shield their children from the harshest of life’s realities. I have a new stack of books to read on Irish history and the Troubles, a new collection of Heaney poems, and a further means of bonding with a close friend who’s an expert in, and passionate about, Irish literature. I also think of the pull Ireland continues to exert on people I love.

My oldest niece minored in Irish literature and language at Notre Dame. She spent a week in Dublin and two weeks in a remote part of Connemara between her sophomore and junior years and four weeks the following summer in Glencolumbkille, a tiny town in County Donegal. Her first summer there, during a stopover in Galway, she and a friend went for a walk and happened upon the writer Colm Tóibín sitting on a bench eating his lunch. He was due to give a talk in Galway later that day, which my niece and the other students had plans to attend. They exchanged hellos and wound up chatting. My niece had Tóibín’s novel Brooklyn in her bag — she had recognized him from the author’s photo on the back — and he signed it for her. After a few minutes, the woman who was with him, in some professional capacity, whisked him away. I was already a Tóibín fan, but when I learned about this happy encounter, I thought, “This man was kind to my niece? I will buy everything he’s ever written.”

My husband and I traveled to Dublin for a few days in March 2001. We hopped over from London, where we were staying with my parents for a couple of weeks while my father was head of Notre Dame’s London program for the semester. We happened to land in Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day, and during our short visit, we enjoyed touring the city, including paying homage to Joyce-related monuments and sites. We went to the Dublin Writers Museum, the Guinness Brewery, to Trinity College to see the Book of Kells, and for drinks at the Brazen Head, Ireland’s oldest pub. And I bought beautiful woolens. Any trip outside the city was off-limits as the U.K. was experiencing an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, and every effort was made to keep it from spreading.

Back in London, my husband and I would go sightseeing all day and regroup at my parents’ apartment before heading back out at night. We’d unwind while watching The Weakest Link. And we watched horrific scenes on the news of towering piles of burning carcasses — livestock that had been killed by the millions to stop the spread of foot-and-mouth. There were also reports of farmers who had died by suicide, in despair at having lost everything. It’s with misgivings, then, that I look back on our trip as wonderful overall. But for us, it was — not least because my parents were healthy at the time. The years of walkers and wheelchairs, cancers and surgeries, lay far ahead. My mother made it over to Ireland that semester, too, to visit the Fauls. I enjoy picturing her with them, talking and laughing, going on excursions, and tracing her own Irish genealogy. While it may be too soon after my parents’ deaths to reflect as intently on their marriage and inner lives as the narrator of Reading in the Dark does with his parents, I can see faint outlines bearing their shapes in the distance ahead—or perhaps it’s the distance behind — that I will strive to shade in as time passes. •