The apocalypse is all the rage these days. Of course, it’s a topic that never completely goes out of fashion. There’s always some person raving on a street corner about how all is lost and a few folks huddled around him or her, eager to listen. But these days, what with climate change, bees dying, ebola, and, of course, the recent election, it’s a topic on a lot of folks’ minds (at least judging from my social media feeds).

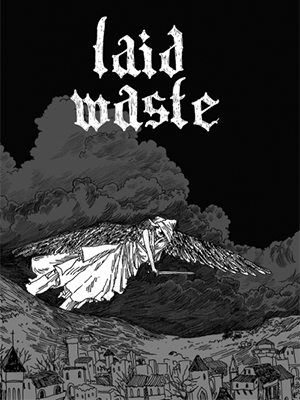

It’s a topic that’s on the mind of cartoonist Julia Gfrörer (pronounced “gruff-fair”) as well, or at least it’s the central setting of her latest graphic novel, Laid Waste. Gfrörer isn’t interested in depicting wanton death and destruction a la Michael Bay, however, as much as she is in depicting her characters’ attempts to find some sense of hope or solace in a world that is swiftly falling down around them.

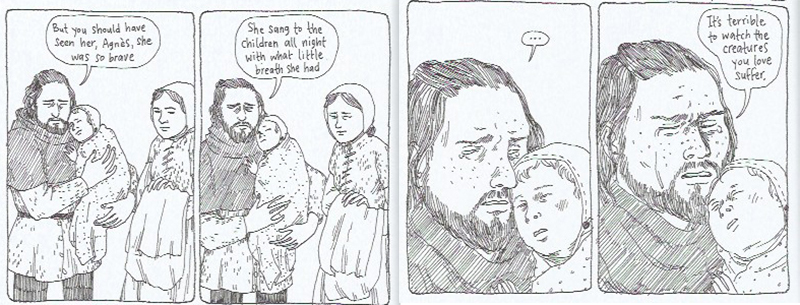

Laid Waste is set in a small, European village during medieval times. The plague has ravaged the landscape so badly that the dead are not buried so much as disposed of in a ditch outside of town. Dogs fight over human limbs. Doctors fall victim to illness and death while treating their patients. To those still living it appears as though the end of the world has arrived.

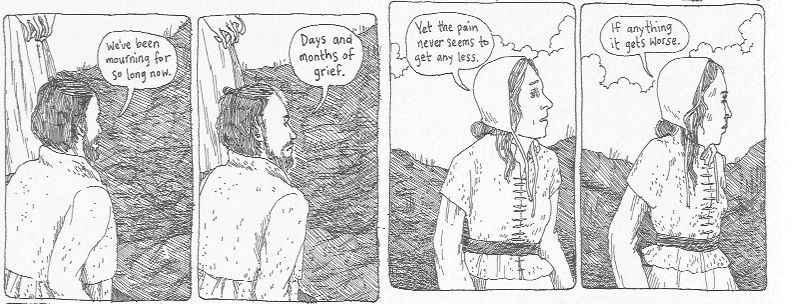

It certainly seems that way to Agnés, a young woman who has lost her entire family to disease but is apparently immune to the plague herself (a prologue suggests there is a supernatural reason for this). Far from viewing her wellness as a gift, though, Agnés regards it as a curse and prays for death to take her since she can do little more than watch everything crumble around her.

Because she often includes supernatural elements in her comics, along with a healthy dose of violence (more on that in a moment), Gfrörer’s work tends to get labeled as horror. Gothic horror might be a better description, though even that appellation seems a bit too pat. More than anything, her comics seem subsumed with expressions of tragedy and grief. Many of Gfrörer’s characters are survivors: people attempting to recover from or deal with severe, life-changing calamity. There’s the forlorn man in her first major work, Flesh and Bone, sobbing over the death of his beloved. The sailor set adrift at sea and staring death in the face in Black Is the Color. The teen girls desperately trying to avoid marauding monsters in Hiders. The 20-something struggling to handle (or avoid) a drug-addicted ex-fiance in River of Tears. Her protagonists are often people straining to juggle the horror that has been visited upon them.

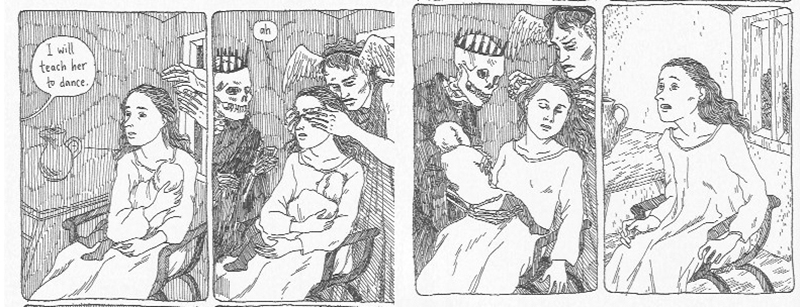

As previously mentioned, she is also not one to shy away from depicting gore. Children are eviscerated and have their eyes gouged out in Flesh and Bone. A Christian martyr has her arm hacked off in Palm Ash. Throats are ripped in Hiders. A young man is molested by a lake monster in Phosphorous (as a brief aside, it’s worth noting that, while far from a hard and fast rule, men and boys are frequently the victims in Gfrörer’s comics, while women tend to serve as catalysts or antagonists). Even when the violence is downplayed (as it is in Laid Waste), there are still malevolent forces or just plain old disease ready to prey upon the innocent.

And yet there is a poetic grace and beauty that suffuses even her most gruesome work. There’s a sense of the ethereal in her comics, a haunting otherness that belies the carnage while at the same time heightening the dread and sorrow. Part of that has to do her artistic abilities. Her razor-thin pen lines are always confident and detailed but also delicate, as though the world she is depicting requires a gentle touch.

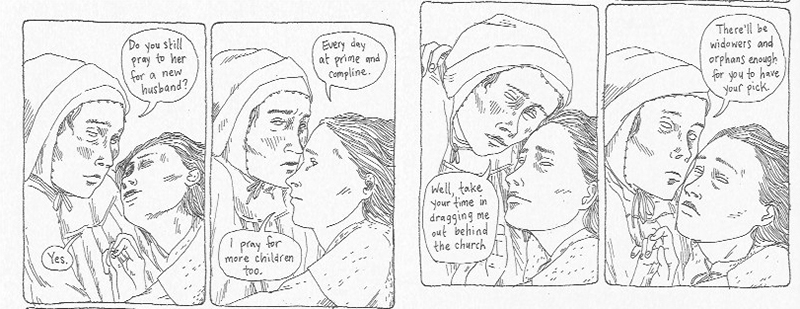

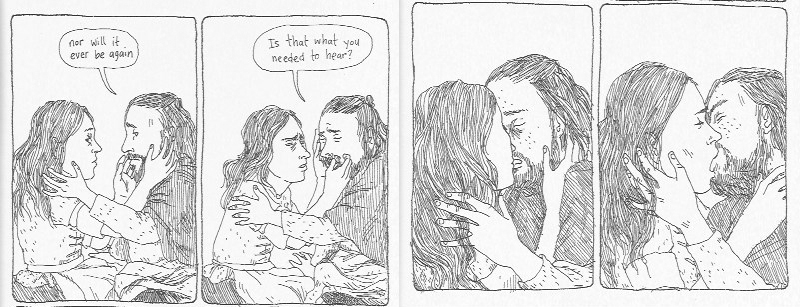

Part of it, however, has to do with her utter fearlessness in depicting sex, often in as explicit a fashion as possible. Far from lurid or salacious, Gfrörer approaches sex in as frank and matter-of-fact (and at times even bemused) manner as possible. Sexuality in her comics is not something to be easily dismissed or tittered about, but an essential facet of her characters’ lives that Gfrörer observes with a deadpan but not uncaring eye, resulting in sequences that can be highly erotic or disturbing (or both), depending on the context. Either way, they are certainly often fraught with emotion. That’s true in Laid Waste, where Agnés and a neighbor attempt to find a moment of solace in each others’ arms.

Yet as much as Gfrörer is willing to depict violence and sex, she can be coy when it comes to other aspects of her work. While the supernatural world appears time and again in her work, she is ambiguous about its true sphere of influence. Is Agnés’ inability to fall ill truly the work of otherworldly forces or just a matter of good genes and weird luck? Does the dying sailor in Black Is the Color actually return home one last time or is that just a dream? Are the creatures in Too Dark to See hallucinations or actual otherworldly spirits? What does the witch in Flesh and Bone think of the grieving man she helps? Gfrörer wisely refrains from revealing too much about the worlds she depicts.

There’s an ambiguity too, at the end of Laid Waste. In the finale, hope is offered. A hand is extended. But illness and death remain, and we know that at least one other person close to Agnés has contracted the plague and will likely succumb soon. Yet in the face of decay and death, what else is there to do but to press onward and believe that things matter? Even in the face of the apocalypse, hope cannot be snuffed out so easily. Laid Waste is Gfrörer’s most emotionally wrenching and heartfelt work to date. •

Images courtesy of the publisher Fantagraphics and author