The cover of Yellow Negroes and other Imaginary Creatures by Yvan Alagbé shows the profile of a young African man with his eyes closed. A pair of light-skinned hands encircles his neck. On the back cover, we see an older, seemingly Caucasian man, balding and with a mustache, his mouth ajar. A pair of dark-skinned hands lies on the man’s shoulders (perhaps belonging to the figure on the front) suggestively seeming to also be inching their way up to the neck.

These two men are Alain and Mario, respectively, the two central figures in the book’s title story. This pair of images might suggest that within lies an overly simplistic story of racial animus, but “Yellow Negroes” (or “Negres Jaunes” in French) is far more complex and haunting than that fleeting impression would suggest. The story has long been regarded as a masterwork in Europe, one of the seminal French comics of the 1990s. Now it’s available in English for the first time, and, despite the considerable span of years and cultures, it — along with the other stories in this slim volume — remains as trenchant and relevant as when it was first published.

Raised in both Paris and western Africa, as a young man Alagbé joined up with fellow artist Olivier Marboeuf to form the comics publisher Amok in 1993. Amok released a number of notable cutting-edge works, including the anthology Le Cheval sans tete (“The Headless Horse”), described by critic Matthias Wivel as “a glove thrown in the face of habitual thinking.” In 2001, the company fused with fellow envelope-pushing publisher Freon to become Fremok and has been going strong ever since.

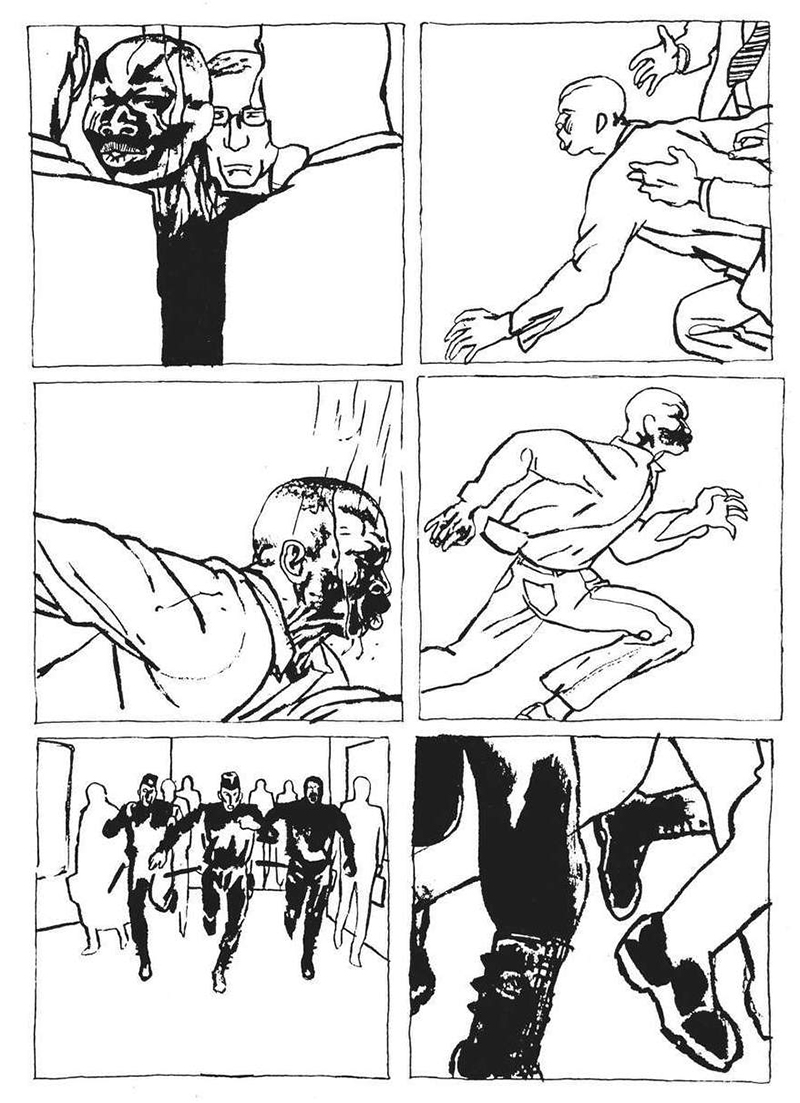

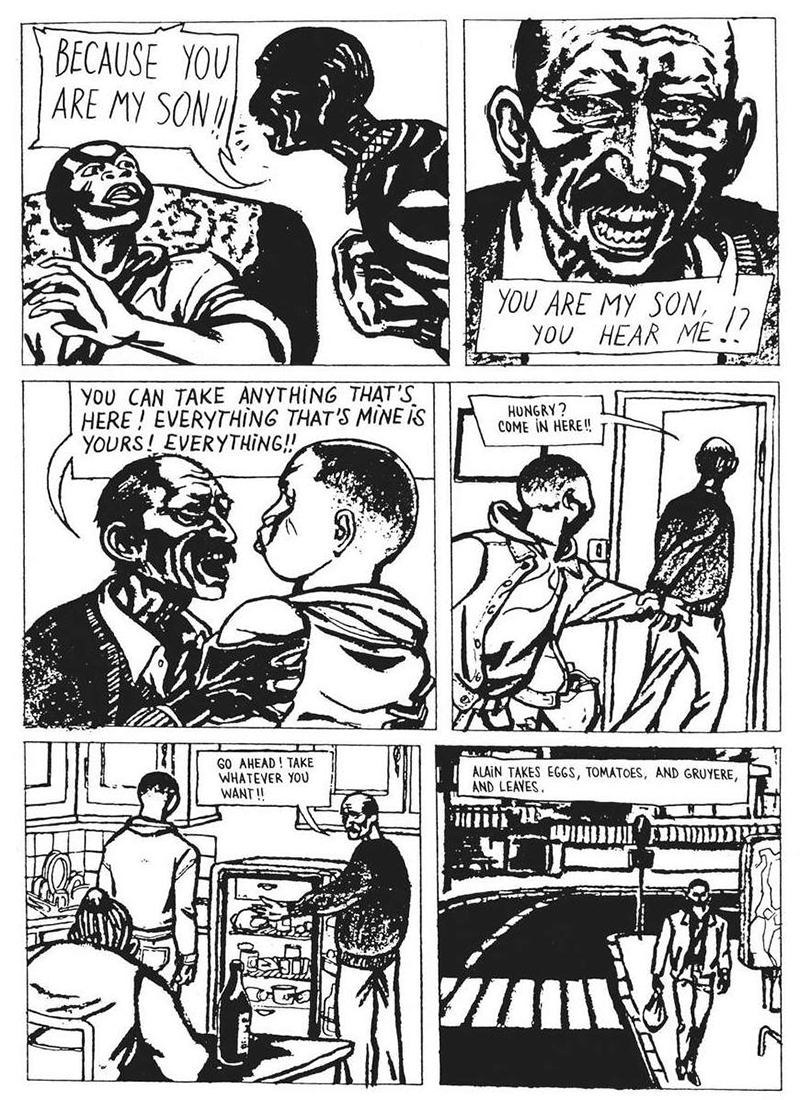

Alagbé’s comics center around issues of class, race, and immigration as his characters struggle to navigate a post-colonial France that is constantly reminding them of their second-class status. In “Yellow Negroes,” Alain is a Beninian undocumented immigrant living in Paris with his sister, Martine, and Sam, an artist (who might well be a stand-in for Alagbé himself). When we first see Alain, he is being berated by his soon-to-be ex-boss, who hurls insults at him, reminding him of how tenuous his residency is.

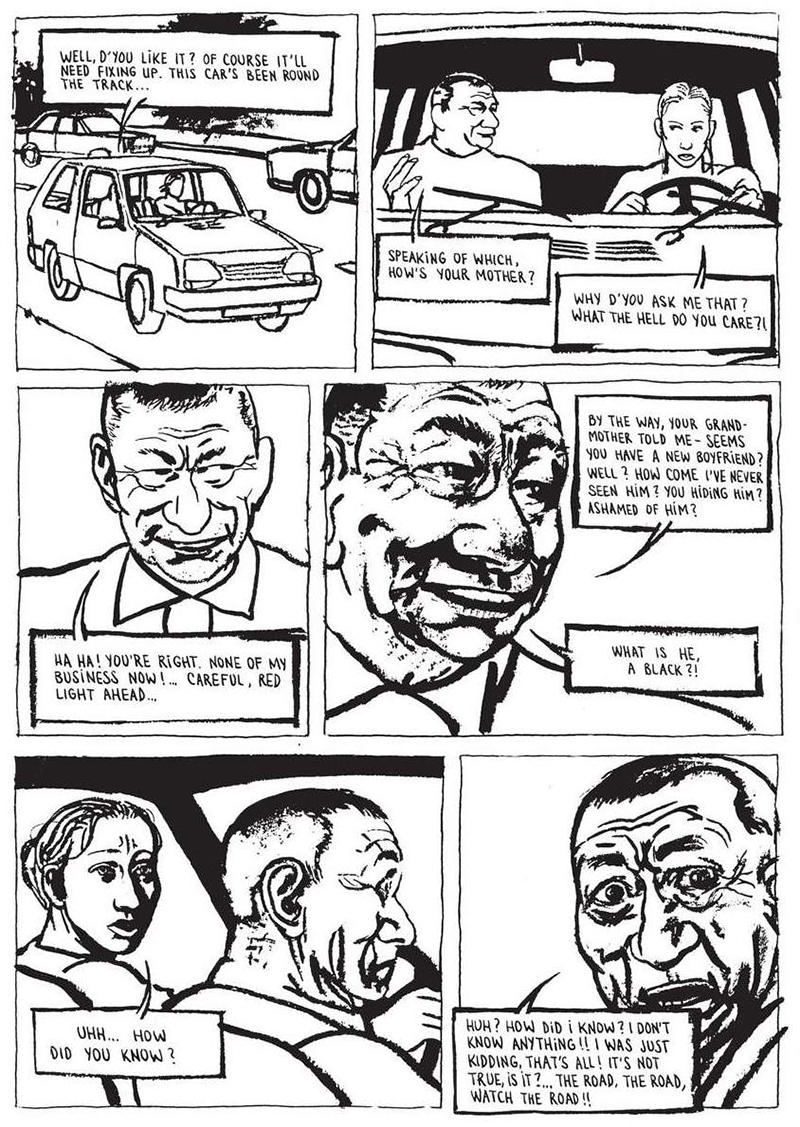

Alain happens to be dating a white girl, Claire, whose family does not — to put it mildly — approve of the fact their daughter is “dating a black” (Claire’s story is expanded upon considerably in Alagbé’s 2013 Ecole de la Misere, which hopefully will also be released in English sometime soon). If Alain married Claire, that would take care of some of his immigration woes, but he is too proud to take that offer (“A whole life to earn, to pay dearly for, and you could never leave here,” he seemingly narrates to himself).

Enter Mario, an Algerian who claims to be a retired cop, telling stories of his glory days in the army and bragging that he still has connections with the authorities, enough to suggest that he could get the brother and sister the proper papers they need to live in Paris without fear.

But it’s clear right from the start that Mario is far too emotionally needy, constantly extending invitations, calling all the time, and making Alain and Martine feel uncomfortable with his talk of order, discipline, and the way things ought to be. Seemingly friendless and ignored by his daughter, Mario gives off a desperate stink of loneliness that these siblings can ill afford to be near.

Through an omniscient narrator (perhaps Sam?), it is revealed that Mario took part in the Paris massacre of 1961, in which French police attacked a group of demonstrators clamoring for Algerian independence, killing at least 40 people, though the actual total is probably more. So in no small way, Mario was participating in the oppression, abuse, and slaughter of his own people, which is perhaps why he so guiltily attempts to befriend Alain and Martine and perhaps why he can find no solidarity among either fellow immigrants or the French authorities he so clearly aligns himself with.

What’s fascinating about Mario is how, despite his crimes, he becomes a pitiable, if not entirely sympathetic, figure. His choice to side with the French and the illusory social order they represent has isolated him in funhouse-mirror fashion to the kind of segregation that Alain and Martine experience. For his own part, Alain is far from a saint, happy to accept the free food and money Mario offers without informing his sister (and becoming more resentful all the while).

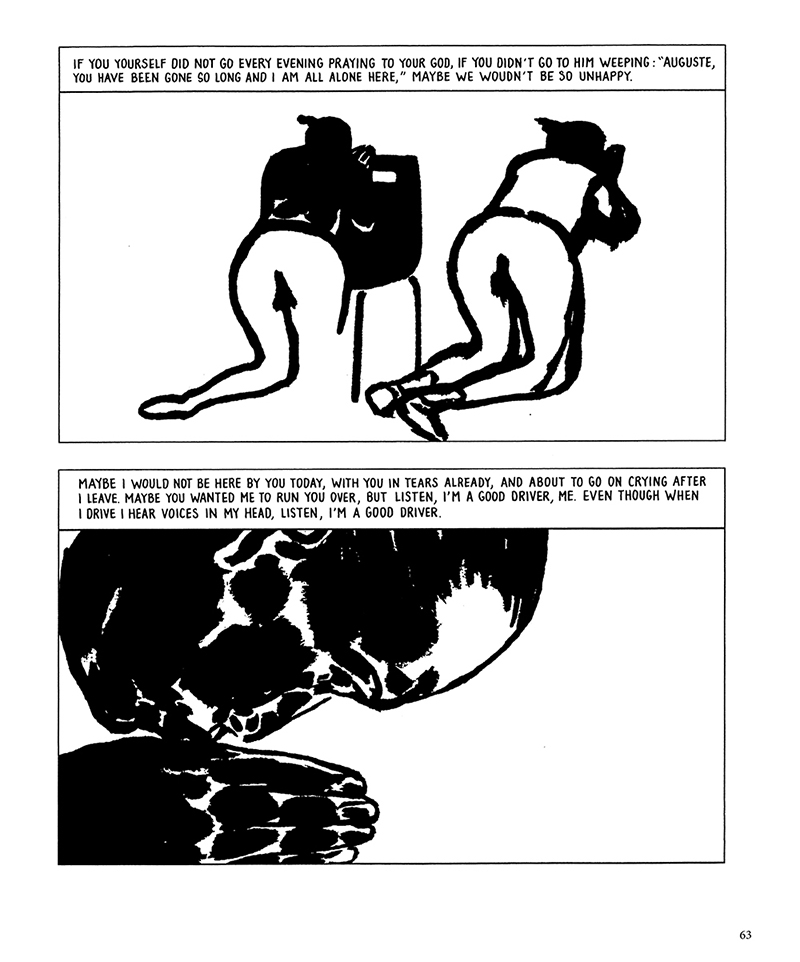

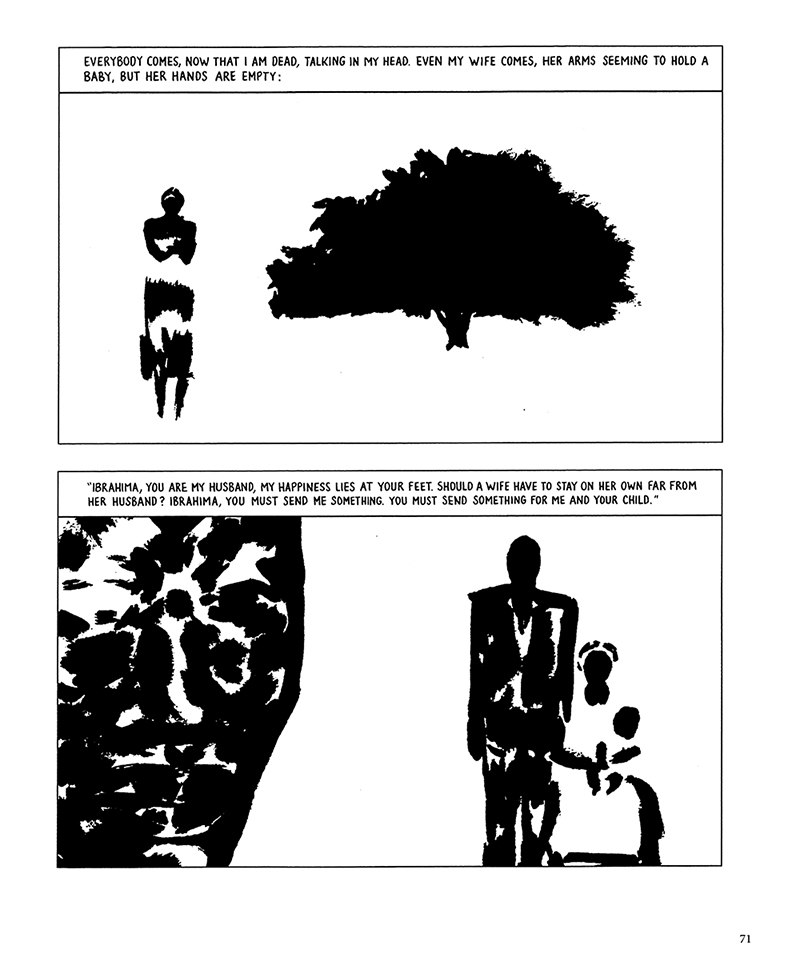

While Alain and Mario’s stories come to abrupt and grim conclusions in “Yellow Negroes,” Martine’s story continues in “Dyaa.” Told from the perspective of one of Martine’s lovers, a taxi cab driver, the story in its own elusive fashion is about how migrants are torn between their families and the culture they left behind and the struggles to build anew in a different country. Martine has a husband who has seemingly abandoned her, while Ibrahima, the taxi driver, is haunted — perhaps literally — by the wife and child he left behind and a village elder who chides him for not sending enough money back home.

The characters in Alagbé’s stories are all struggling to overcome the weight not just of their current plight — their solitude in a foreign country and ache for the life they knew — but of history itself, the racism and oppression formed ages ago that continues to prey on them, victims of a government and society that need but do not necessarily want them around. In the book’s final story, “Sand Niggers,” made expressly for this North America edition, Alagbé draws a line from the 1961 massacre to Donald Trump, shown signing executive orders designed to throw more and more people out of the U.S. The past, Alagbé reminds us, is always present.

I’ve talked a lot about the plot, themes and characters in Yellow Negroes, but Alagbé’s art style is perhaps the most significant and striking aspect of his work. If his prose favors the subtle and poetic over the straightforward, his art can be even more enigmatic (and in case I haven’t made it clear yet, this is a book that requires — perhaps demands — close, repeated readings).

Alagbé’s art style is often deliberately rough and sketchy, switching from realistic, figurative representation to more abstract images and back again. “Dyaa,” for example, is drawn with thick swaths of ink, with the characters often rendered as silhouettes against a blank background. A better example is the opening story, “Love.” At first, we see what looks like an abstract arrangement of jagged and wavy lines. Only upon turning the page do we realize we’ve been looking a the back of a naked woman. As the comic slowly pans around her, we see a dark object in front of her, which is eventually revealed to be a small black child, breastfeeding.

What’s interesting about Alagbé’s comics is what he chooses to leave out or not draw, just as much as what he puts on the page. Alagbé will frequently render a character in full detail with thick black shadows surrounding them in one panel, only to delineate them in the barest, most minimal line possible, often omitting key sections of the face or figure, in the next. Alagbé draws a prostitute mocking Mario, for example, as a white silhouette — except for the center of her face, which expresses laughing scorn.

In “Postcard from Montreuil,” Alagbé observes a group of undocumented workers on a street corner protesting unfair treatment. They are there for almost a year, until one day they simply aren’t, with no evidence they had ever been there. “Telling tales is the business of survivors,” Alagbé writes at the end of this book, though he wonders if he is capable of telling these stories of the forgotten adequately: “Can the world hold all the woes of the world? Can my love?” And yet here we have a book quite unlike any other, both in terms of aesthetics and subject matter: one that deals with its important, complex issues in an important, complex manner. Alagbé’s love might not be capable of holding all the world’s woes, but what it does contain is significant. •

All images copyright by Yvan Alagbé.