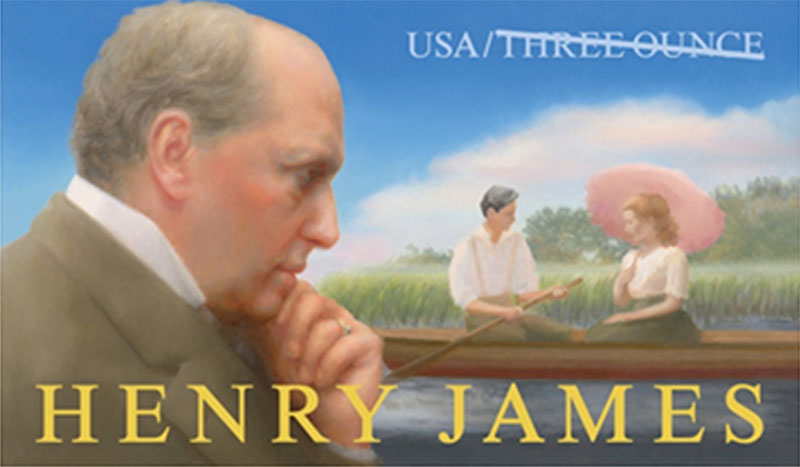

On July 31, the U.S. Postal Office issued an 89-cent stamp in honor of Henry James. The issuance is part of the Postal Service’s Literary Arts series — James is the 31st figure in American literature to be so honored.

It is ironic that the stamp arrives on the centennial anniversary of James’s death and the year he became a British citizen. This was done as an expression of support for England’s war effort in World War I (Americans would not enter the war until April of 1917). Yet for all his gratitude to England, his loyalties never fully strayed from his native land. James’s novels and stories are full of American characters, often naïve and foolish, but also upright and brave — always morally superior to their more worldly European counterparts. It is therefore fitting that he be honored as an iconic American, worthy of his own postage stamp.

It is also fitting that the end of James’s life be celebrated. This was when he ascended to the “major phase” of his writing career — when he became, as his most important biographer and critic, Leon Edel, put it: “the Master.”

Although James’s early writing is more accessible and widely read, his late work is more important in the history of the novel and, arguably, in culture more generally. These late books are stylistically tortuous, prompting one of his friends to remark famously that he “chews more than he bites off.” (The quote has been attributed to a number of people, including Oscar Wilde and Henry Adams. Whoever said it first, others apparently found it so apt that they were prompted to repeat it.)

James’s dense and difficult style meshed with a shift in orientation in his later work. If you can grope your way through late James, you’ll find you have moved out of the Victorian era into the modern and, beyond that, into what we have come to refer to as the postmodern. This postmodern James is a harbinger of some unfortunate trends in our society today. It’s hard to believe that the difficult late writing of this long-dead writer has had a dangerous effect on our time, but — Jamesian enthusiast though I am — I am obliged to admit that this is so. But I’ll get to that.

Henry James was born in 1843 into a New York family of inherited wealth. Encouraged by his eccentric father to be unconventional, he abandoned law school for literature. He moved, gracefully but definitively, away from his geographical roots, expatriating himself first to Paris, then to London, where he would spend the majority of his writing life — though making regular forays into Italy for the art, architecture, and food.

As he moved into late middle age, James revamped the novel form to a point that exasperated many of his readers. Among them was his older brother William who, on the publication of Henry’s especially difficult late novel, The Golden Bowl, wrote:

Why don’t you, just to please your Brother, sit down and write a new book, with no twilight or mustiness in the plot, with great vigor and decisiveness in the action, no fencing in the dialogue, no psychological commentaries, and absolute straightness of style?

William James, a pioneer in the fields of philosophy and psychology, remained attached to realism and clarity in his taste for fiction.

But Henry James had left that kind of writing behind as he crossed from the 19th century into the 20th. His superficial kinship was with European modernists like James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf. Late James is often opaque, as his brother’s comments indicate — and opaqueness was a hallmark of the modernist rejection of facile realism.

James was also superficially modern in his predilection for the new tools of the new age. One of these was the typewriter. In his last years, he dictated his novels to his typist. It has even been speculated that the cadences of his late work follow the rhythm of the typewriter, punctuated by the bell as the machine moves from line to line. As he lay on his deathbed after a stroke, he was soothed by the tapping of the typewriter keys as they recorded his garbled dictation.

Along with the typewriter, James was also enamored of the nascent narrative form of movies. This jibes with his turn to the “scenic” in his late novels, following his attempt in the 1890s to write for the stage.

James’s effort at playwriting failed. He was booed by the audience when his play debuted in 1895. It seems he could no more enter the visual realm first-hand than he could use a typewriter on his own. One is tempted to connect this failure to the pull of his Victorian roots. The Victorians loved clutter and ornament, and Victorian writing is notable for its verbosity. One could argue, in fact, that James could appreciate aspects of the modern but could not incorporate them fully into his work. (Although there have been a few movies and multi-part television adaptations of James’s late work, these have not been successful, suggesting that the visual medium did not suit him.)

But there is another way of seeing James’s unfulfilled relationship to modernity — not as a lagging behind but as a jumping ahead. His late writing in no way resembles that of his verbose Victorian predecessors. It is dense and difficult in an entirely new and forward-looking way. James loved paradox — and the idea that he might have been too modern to be a modernist would have pleased him.

Looking over the Jamesian canon, one sees a range of themes relevant to us today. Some examples: the difficulty of reconciling feminist self-assertion with heterosexual marriage (The Bostonians); the moral difficulties associated with revolutionary idealism as it merges into terrorism (The Princess Casamassima); the effects of divorce on a child (What Maisie Knew); and the dangers of parent-child enmeshment (The Golden Bowl). James also anticipated globalism with his celebrated treatment of what he called the “international theme.”

But what seems most postmodern about James’s writing is conceptual rather than thematic. There is an indeterminacy with respect to truth that his later work supports in such an aggressive way that it becomes a worldview. Words, normally meant to communicate, are deployed more as obstacles to communication than as facilitators to it. The fragmented nature of his dialogue leaves meaning unresolved between characters (he describes them as continually “hanging fire”). As for the narrative aspect of his writing, it often requires several readings before the reader knows what’s going on. Consider, for example, the opening sentence of his 1902 novel, The Wings of the Dove:

She waited, Kate Croy, for her father to come in, but he kept her unconscionably, and there were moments at which she showed herself, in the glass over the mantel, a face positively pale with the irritation that had brought her to the point of going away without sight of him.

The sentence is long-winded, but it is more than that — it is engineered to postpone and confuse, to push us forward, but as if in the dark.

As early as the 1881 Portrait of a Lady, James had begun to explore a new perspective on the world. Of the heroine, Isabel Archer, the narrator writes: “Her love of knowledge coexisted with the finest capacity for ignorance.” Clearly, the narrator is telling us, there is value attached to having “the finest capacity for ignorance.”

Where the Romantic poets had viewed the imagination as a liberating force in the relationship to nature, James made the imagination liberating on a grander scale — a way to remain free to see the world in whatever way one pleased. This approach to representation leads beyond the alienation of modernism to the free-floating, provisional connectedness associated with postmodernism.

James demonstrates his method in his late novel, The Ambassadors. In one important scene, his hero, Lambert Strether, finds himself rowing on a lake where he encounters his friends, Madame de Vionnet and Chad Newsome, approaching in another boat. Catching these two people unaware in this remote locale, Strether cannot avoid the conclusion, that he has thus far managed not to believe, that they are lovers. No sooner is he away from the scene, however, then he returns to his original sense of indeterminacy regarding their relationship. He can, through his imaginative will, erase the facts that the pictorial moment had seemed to definitively relay. A character like Strether is an extraordinary creation. He gives readers access to a mind so fine that it can ignore — or transcend — concrete visual evidence.

Strether’s perspective has a kinship with the critical method of deconstruction, the hermeneutical approach that became popular in academia toward the end of the 20th century. All meaning, for the deconstructionists, is provisional, a function of the eternal “play of the signifier.” It is, of course, a stretch to link the rise of an entire critical method (ostensibly French in origin) to the work of a writer born in America more than a hundred years before. But if there is a singular imagination that laid the ground for this way of thinking within an Anglo-American context, it is Henry James. The number of writers influenced by James, dating from the middle of the 20th century through to the present, is legion. Philip Roth and Cynthia Ozick, David Lodge, Colm Toibin, and Alan Hollinghurst are most notable for their use of Jamesian characters and motifs in their fiction. But there are plenty of others who have been influenced more obliquely by James or by other James-inspired writers. And to know the Jamesian sensibility, even second-hand, is to begin to see the world the way Lambert Strether did.

James used his approach to moral ends. His characters were always trying to make the most out of situations and see the best in people through their imaginative flexibility — to salvage meaning to some positive, creative end.

The problem, however, is that this approach to life can cut both ways. It can serve a discriminating and compassionate imagination or a selfish, even malevolent one.

Deconstruction, creative and empowering though it was in some respects, had already begun to do harm within academia as it gathered force in the 1980s and ’90s. It allowed some to use it for dubiously righteous ends, creating a highly polarized environment within academia. It allowed those who practiced it to set themselves up as rhetorically virtuous and lord it over those who had not mastered (or chose not to support) this interpretive approach. Now, these effects have overstepped the confines of the Ivory Tower and taken a populist form where the results threaten to be truly dangerous.

The “play of the signifier,” a source of creativity to Henry James and empowering to an academic elite, is now in the hands of demagogues and bullies. Facts are bypassed or subverted; words acquire a plastic, purely provisional meaning based on what the speaker wants to relay and the listener/reader wants to hear. History becomes what one wants history to be.

James would have been appalled by this state of affairs, which betrays the ideals of his moral imagination. And yet his great later writing can be seen as its precursor. •

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).