I am not interested in writing about the deafening kind of noise that causes irreversible damage to the human ear. Nor in the wide range of sounds that you can hear outdoors, like the roar of surf, birdsong, or wind. What interests me far more is that elusive category in-between. Ranked highest among the sounds I find most unpleasant are: compulsive and demonstrative finger-cracking in libraries, and the high-pitched squeal of feedback from PA systems. Others can be driven insane by a dripping faucet, or even a ticking alarm clock, elevator music or in-store Muzak — noise that we have to hear whether we want to or not. My neighbor owns an admittedly quite attractive hunting dog that is genetically hard-wired to bark incessantly, or so she tells me. Why she has to keep this dog in the middle of a city is beyond me, but that’s beside the point here.

If you think you fall into the category of noise-sensitive people, you are in good company. It is known, for example, that Proust’s smoke-filled study, which doubled up as a bedroom, was completely soundproofed with cork. Hypersensitivity to noise doesn’t automatically qualify you to write masterpieces. But the renowned Frenchman knew how to tap his remarkably acute perception to be extraordinarily, even enviably prolific. Noise, in his opinion, was a kind of assassination of the senses. However, his labored breathing was beyond his control. Luckily, it was so loud that it not only drowned out the sound of his quill, but also the construction work being carried out on a bathroom a story above him.

It is astonishing, but also comforting, how we can get used to recurring, predictable sounds. Some time after I moved into an apartment that was directly above Berlin’s U4 subway in the district of Schöneberg, I was regularly woken at 5 AM by the rumbling of the first train. The subway tunnel, dating back to 1910, wasn’t built as deeply as modern lines, but directly under street surface instead. The sound of the rolling carriages varied; on some occasions, it was louder than others. But soon, I became less and less aware of it, obviously having grown accustomed to it. And if I did hear it on the occasional morning, it was a pleasant sound. So not only had I accepted the noise, I’d even started to associate it with my feeling of well-being at home. Looking back, what seems decisive about my change of heart was, firstly, the regularity of the sound and, secondly, the fact that it didn’t exceed a certain threshold. It was also inescapable: I came to terms with it because the alternative would have been to move out again.

Some reactions hark back our distant past when we had to watch out for natural dangers — wild animals, for example. And a screaming child is sure of his parents’ undivided attention, because noise here serves as a warning signal, whereas strangers just roll their eyes. This is the conclusion reached by scientists who investigated the acoustic characteristics of screamed and spoken language, or more precisely, the frequency with which volume and pitch change. In normal speech, this modulation frequency is very low — the changes are slow, in other words, not going above 20 Hertz. Screaming, on the other hand, covers the range between 30 and 150 Hertz. Acousticians define this area as being “rough” in timbre. “The roughness of screaming is the acoustic equivalent to the rapid flickering of a disco stroboscope,” explains Luc Arnal, a neuroscientist at the University of Geneva.

Some decades before Proust, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer targeted noise as the supreme archenemy of any serious thinker. His biggest gripe of all was the “infernal cracking” of coachmen’s whips: a perfectly futile action since the horses were long desensitized to it. What measures can we take against unnecessary noise? Not everyone can afford the luxury of sealing herself off from the outside world of noise, only venturing out if absolutely necessary. The New Yorker Julia Rice had highly idealistic aspirations when she founded the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise in 1906. Rice argued that the city’s poor suffered miserably on account of tugboat noise. The campaign was related to the idea of a neurosis called “Newyorkitis” — an illness that arose from an unhealthy addiction to noisy environs. Her campaign was crowned with success: in 1907 Congress signed a law reducing the frequency of ships’ whistles in federal waters, which almost always had the function of saluting colleagues. However, Rice seems to have enjoyed quite a bit of noise in her life: her six children played instruments and the family allegedly kept a number of cats and dogs. She probably would have classified all this as “necessary.”

How have people from other eras and cultures perceived the world of sound? There is a certain appeal in imagining these soundscapes from the past — the endless clattering, clacking, hammering and shouting that went on in medieval towns (not to mention the stench), for example, in which people were trapped and forced to accept as inevitable. But although we might have a dim inkling of how things used to sound, we cannot “hear” them exactly because we all store the experience of our own soundscapes: our hard drives can’t be wiped clean and started from scratch, as on a computer.

It sounds like a paradox but the quieter our environment is, the louder it feels to us. When we move from a busy main street to a quiet residential area, we hear the slamming of a car door in a very different way to before. It seems louder because it stands out from the peace that reigns otherwise: the relationship between noises changes. And if our ears are already sensitized to particular noises — if we have been het up over our neighbors’ loud fights, for example — then we almost start listening out for them again.

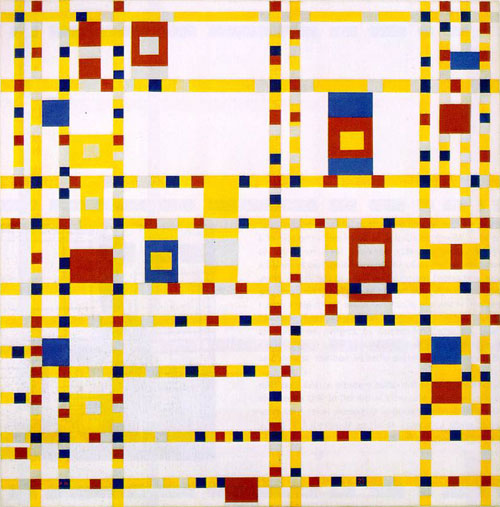

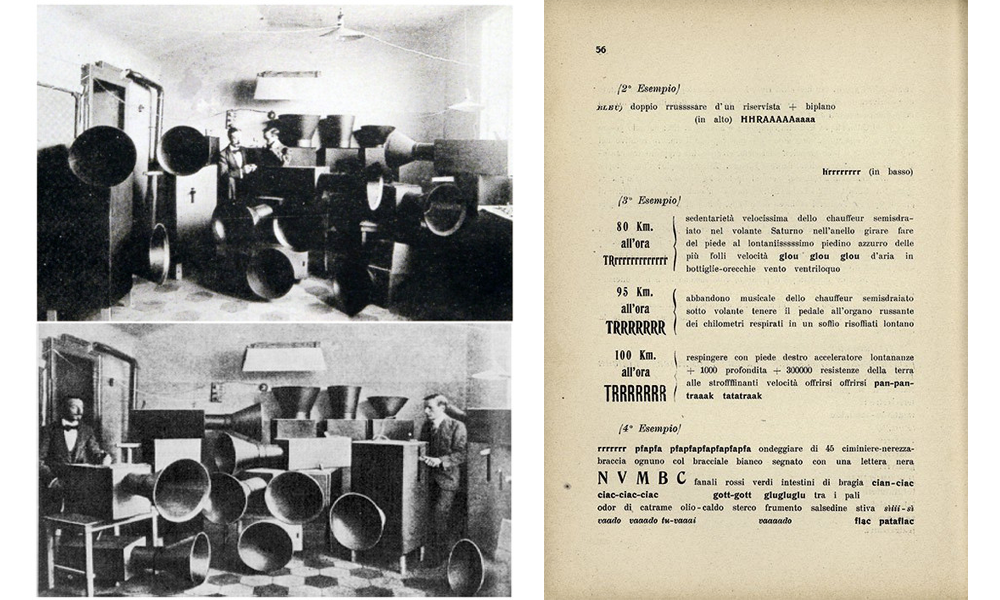

Loud “casserole” protests, where demonstrators bash pots and pans on the streets at deafening volume, are a way for people to vent their anger against governments. They also illustrate that whether something is considered noise or not depends on your point of view — or in this case, your politics. For Luigi Russolo, the Italian futurist, noise was an expression of strength and masculinity. He celebrated it; the rattling of machines inspired him. He also wrote a pamphlet entitled The Art of Noises (1913). Is whether we perceive noise as such a matter of attitude? “Wherever we are what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating,” said John Cage.

What role does noise play in the lives of animals? In Switzerland during this hot summer, there was a controversy over whether cows that wear bells around their necks might suffer damage to their hearing. “For the cows, these bells are as loud as if a pneumatic drill were held to our ears,” claims Nancy Holten, a Dutchwoman and resident of Switzerland. Her Facebook page “Kuhglocken out” (“Cowbells out”) has 4,000 followers. She refers to research from scientists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, who investigated the effects of cowbells on the animals, and found that those wearing bells ate and rested less than those without. Said bells have the considerable volume of 113 decibels. To illustrate the animals’ plight, Holten posted a photograph of herself with a 12-pound-cowbell around her neck. She advocates the development of special GPS devices with which farmers can easily locate their herds. Some activists have cut the cowbells from the cows’ necks and have made off these valuable items. It remains to be seen how the controversy ends. As incredible as this may sound, elsewhere, the Swiss are feuding over church bells that regularly jolt people awake.

As enticing as peace and quiet might be for stressed fellow humans, would we really want absolute silence? Some might, but we should bear in mind that absolute silence does not make for a good life. If you sleep in a completely noiseless room, for example, you become hypersensitive to the sound of your own breathing, which can even stop you falling asleep — because complete silence simply sets our alarm bells ringing. •

Translated from the German by Lucy Renner Jones

All images via Wikimedia Commons and by the artist noted. Lead image: Luigi Russolo, The Revolt (1911).