It’s been a little over a year since Ari Banias’s first poetry collection, Anybody, debuted to critical accolades and honors, including a nomination for the PEN America Literary Award. With all that has happened since 2016, this stunning, complicated book is worth revisiting and considering through the lens of our particular political moment. Donald Trump has fulfilled the divisive promises of his presidential campaign: Standouts among his many troubling actions are cancellation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, attempts to ban immigration from Muslim-majority nations and bar trans people from serving in the military, and his support of U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore, the bigoted, twice-fired Alabama judge and accused child molester. The #MeToo movement has also shed light on the systemic abuse of women by powerful men, including Trump himself, whose accusers are calling for him to be held accountable for alleged sexual assaults. At the same time, social media has amplified many historically marginalized voices, sparking crucial conversations on the national stage about racism, sexism, and LGBTQ+ discrimination. In this way, Anybody feels prescient. Not because it deals with any specific politics, but because it dramatizes the individual’s search for wholeness and community within a broken society.

The first poem, “Some Kind of We,” announces the deep wish of Anybody: To push beyond the singular self toward a collective, to move from an “I” consciousness to a “We.” The lyric begins with the traditional first-person speaker cataloguing his surroundings and thoughts: “These churchbells bong out / one to another in easy conversation / that wants to say / things are okay, / things are okay — / but things / they are not okay, and I can’t / trust a churchbell, though I would like to.” The voice is charming, familiar as the sound of churchbells, with a surprising intimacy that disarms us by sharing a secret. And that secret happens to be one we share: Things are not okay. The world is a mess. We, too, wish we could take comfort in churchbells or religion. But we’ve lost our faith. That’s why we need poetry, a kind voice with whom to conspire. This is what Banias offers his readers — and then some. For this poem — like Anybody as a whole — does much more than mirror our sadness and alienation. It unpacks the conditions of that sadness and alienation, poking at our basic assumptions about self and its relationship to others. It does this by continually interrogating its own expression and making. In “Some Kind of We,” for example, Banias seizes upon the image of the “plastic bag,” describing his “overflowing” collection of bags in such detail that it becomes a metaphor for capitalism’s emphasis on things rather than human relationships. Rather than being satisfied with this metaphor, however, the poem makes a metacognitive turn as the speaker questions his choice of imagery. He confesses: “I / am trying to write, generally and specifically, / through what I see and what I know, / about my life (about our lives?), / if in all this there can still be — tarnished, / problematic, and certainly uneven — a we.”

Read It

Anybody by Ari Banias

Those first three lines might draw laughter from a fellow writer, to whom this dogma is all too familiar: Write what you know. The idea is that if you do so competently, your singular story will represent “human experience” writ large, transforming the work of literature into a mirror for the reader. The deep flaw in this logic, however, is that “human experience” has historically been shorthand for the life of a cisgender, heterosexual, white male from the upper or middle class — the sort of person who has dominated the Western literary canon for centuries. “There is the falsely mystical view of art, that assumes a kind of supernatural inspiration, a possession by universal forces unrelated to questions of power and privilege,” Adrienne Rich wrote in her 1983 essay “Blood, Bread and Poetry: The Location of the Poet,” in which she chronicles her struggle to value her voice as a gay woman while interrogating her own privilege as “white in a white-supremacist society.” An intellectual descendant of Rich, Banias created a book sustained by this problem: how to square one’s knowledge of a limited self with the writer’s genuine desire to commune with the reader, whose identity might differ wildly from the poet’s own. The literary canon’s historic failure to confront this problem has contributed to real-world injustices, which Banias describes in an interview with Lambda Literary: “I think of how the unnamed default of whiteness has been inherent in ideas of universality and humanness, and how that default is an erasure tied to projects of actual, material erasure — displacement, colonization, war, slavery, mass incarceration.”

In some poems, Banias clearly makes visible what’s been erased. In “Recognition is the Misrecognition You Can Bear,” for example, Banias remembers that the polluted Northern California landscape he now inhabits once belonged to indigenous peoples: “Now I’m standing at the edge of this lake / Ohlone fished then white settlers turned / into a sewer.” In other poems, Banias’s strategies to confront historic erasures are more oblique. Consider “On Pockets.” As with “Some Kind of We,” the poem begins by fixating on an image. Pockets “have so many ways of being / prominent or discreet or altogether hidden / buttoned snapped zippered flapped but then also those / on fine suit jackets one has to slit the first time with a blade / the care of that and how sexual it is.” Banias goes on like this for more than two dozen lines, enthralling the reader with his virtuosic transformation of this mundane object into a potent symbol of the human condition. But Banias pulls the rug out from under the reader, ending the poem on a sudden chilling revelation: “today I saw an old friend in a strange yet handsome dark wool coat that struck me / I couldn’t say why, its eerie beauty / and I told him so, he said there are no pockets it’s a prisoner’s / coat.” Suddenly the speaker’s subject position crashes into that of another: the prisoner. Banias’s clever sartorial metaphor seems to taunt this figure, who is denied the privacy and intimacy Banias attributes to the pocket. While race isn’t mentioned specifically, it enters as the elephant in the room of this poem, for nearly 60 percent of prisoners in the United States are Black or Latinx, though those two groups represent less than 30 percent of the nation’s population. And what of our extrajudicial prisoners, the hundreds of Muslims who have been kidnapped and interned at Guantánamo Bay and other “counter-terrorist” detention centers (to which Trump has threatened to banish others). The distance between the speaker and these people makes the “we” yearned for in Anybody’s first poem seem impossible.

Although Banias is a free, educated white man — and the speaker(s) of his poems inevitably embody that subject position to some degree — this is complicated by the fact that Banias is a trans man, as he discusses with Lambda Literary. Many of Anybody’s poems deal with trans identity and selfhood, to which the question of pronouns can be existential and “we” does not always represent an ideal. In “Grandchild,” the speaker of the poem is grappling with his gender being misread by his grandmother, who calls the speaker a “beautiful girl” though he sports “hair barber-cut” and “chest inside two sports bras flattened / further by the fabric bandage we pin close.” This is the double “we” of trans identity. The speaker is not one with the “beautiful girl” but rather sees her as an Other, a separate someone with whom he shares a body: “our hair,” “our torso,” “our name,” “our face.” Yet even in sharing, this “we” constricts, is “narrow,” as Banias phrases it to Lambda Literary. A similar reversal comes in the poem “Double Mastectomy,” in which the speaker’s use of the singular marks the powerful autonomy achieved through top surgery: “the possibility of / my body.”

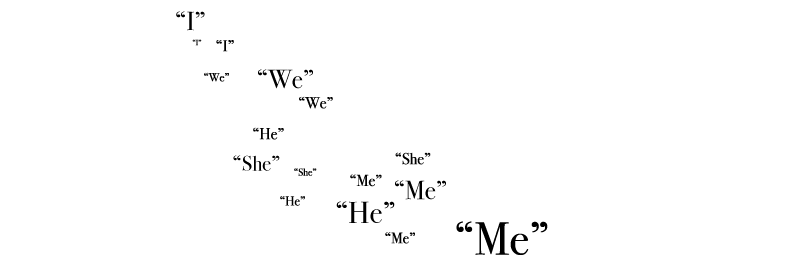

The collection continuously and variously interrogates pronouns. The overall strategy is encapsulated in the poem “Various Attentions All Landing Like Birds Into the Same Tree and Thrilling There Some Minutes at Dusk,” in which Banias writes, “Wrestle down ‘I’ with ‘we’ / Then wrestle down ‘we’ — (still hold dear / experience & consciousness as lived by an each.” Anybody’s speakers are perpetually engaged in activities of identity construction, busy looking through windows, surfing the internet, watching TV, snapping photos, gazing into water, or even peering into holes, which offer anti-reflections: “relatives long-dead, the hands / refusing to release you even / after grace has ended” (from “The Hole”). The search for a coherent self is important to this collection, but Banias — a poet in the age of social media’s aestheticized, digital selfhood — warns against solipsism. However hopefully Anybody opened with the possibility of a “we,” the collection marches toward apocalyptic revelation. In the final poem, “No More Birds,” “we” has destroyed the world with “our plastics and forgetfulness and bombs, / bombs of much unnumbered rubble, bombs of the reasonable / fear of bombs, dividing the living / from the living, towns from towns.” In this landscape, neither “we” nor anyone else has room to operate: “No more branches, no more moon, no more / clouds, light glinting on / no more water.”

This bleakness is somewhat mitigated by the expected entrance of some yet-unidentified Other: “Whose turn is it to open-throated sing? / And what world’s turn is it / to be sung of,” asks the speaker of “No More Birds.” But is this a savior or a tyrant? One wonders, trembling, if this isn’t some premonition of Trump slouching toward Washington. The bombs of “No More Birds” sound especially menacing in light of our escalating nuclear tensions with North Korea, care of Trump’s Twitter-baiting of Kim Jong-Un. Banias ends the poem with a father-like shush, as if rocking a crying baby: “Listen, / time to quiet down, beauty. Time to world.” Not only pronouns are up for grabs in this new world, but all of language. In using the noun “world” as a verb, Banias reminds us of the planet’s power to act. And act it does, climate change being the massive action Earth is in now the midst of performing. Meanwhile, Trump has moved to extract the United States from international climate accords designed to dampen global warming and has rolled back various environmental protections. Who voted him into office? I didn’t. We did. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.