Bill Traylor was too busy painting to talk about painting. In a span of about four years, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, on a sidewalk on Monroe Avenue, in the black enclave known as ‘Dark Town,’ in front of the funeral parlor where he sometimes slept, in the city of Montgomery, Alabama, Bill Traylor made over 1,200 hundred drawings and paintings. He was an old man by the time he started painting in earnest — around 85. He had moved to Montgomery when he was 75, working as a laborer and for a short while in a shoe factory. Before that, Bill Traylor spent his life as a sharecropper on the Alabama plantation where he was born. Before that, Bill Traylor was a slave.

- “Bill Traylor: Drawings from the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts,”

American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Through September 22, 2013.

Charles Shannon, a young white New Deal artist, became fascinated with Traylor when he saw him on the sidewalk one day in the spring of 1939. “[Traylor] was beautiful to see,” Shannon would say many decades later, “so right with himself and at peace…” Shannon would come to Traylor bringing art supplies and enthusiasm, told Traylor his art ought to be shown in galleries and museums, bought up every painting of Traylor’s he could for fear they would be lost. Traylor liked the cheap poster paint and crayons Shannon brought him, but he rejected the fancier supplies. Traylor liked to paint on worn-out cardboard, discarded shirt boxes, and stained advertising signs, the residue of city life. Sitting together on Monroe Avenue, Shannon would ask Traylor about his paintings. But the answers were usually vague. The titles that were later given to Traylor’s works are a distillation of the conversations the two artists had: “Untitled (Man with Pipe),” “Untitled (Construction with Waving Man and Umbrella),” “Untitled (Exciting Event with Keg).”

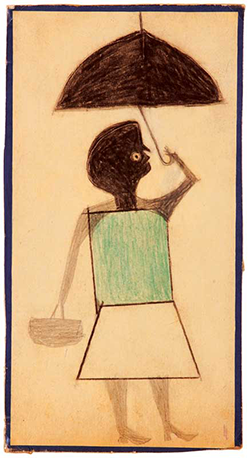

“Untitled (Figure Construction with Waving Man,” c. 1939-1947

The people Traylor depicted in his paintings (many of which can be seen at the American Folk Art Museum’s two current Bill Traylor exhibitions, June 11 – September 22, 2013) lean this way and that. They dance and point and run and shout. They bend their contorted backs, drinking with one hand while trying to keep their balance with the other. They kick their legs in the air and march and pose. They hold umbrellas and birds and hammers and axes. They dangle over and fall backwards off building-like shapes Traylor called “constructions.” The animals in his paintings have sharp teeth and wide eyes. They have a primitive quality, like animals you might see in cave paintings from 30,000 years ago. Sometimes the people and constructions and animals all appear together in one painting. Those paintings are called “exciting events.” Bill Traylor’s “events” evoke the mysticism of the Deep South: hellfire preachers and Judgment Day and Hoodoo and spirit animals.

“Untitled (Exciting Event: House with Figures,” c. 1939-1947

At the same time, Traylor’s art is simple. The materials are plain and accessible. The figures are not supported by any landscape or environment; there is little attention to perspective. “He never agonized over his work,” Charles Shannon once said of Traylor. “He’s the only artist I knew who didn’t. He was very serene. He rarely erased. He just started out and worked to a conclusion. He didn’t fuss with things. He made up doing the rectangles himself and used colors straight out of the jar. Nobody could have told him how to do what he did.” For many fans of Bill Traylor, this directness has only added to his art’s mystique. Traylor’s paintings have come be to thought of as primal, elemental, eternal.

It’s also possible that Bill Traylor simply drew what he saw. As Fred Barron and Jeffrey Wolf (currently making a documentary about Bill Traylor) have written, the six-block district that spread from the corner of North Lawrence Street and Monroe Avenue was the heart of Montgomery’s African American community. The streets of Dark Town were “bustling” and “chaotic”, a thriving neighborhood of “black-owned and -operated newspapers, restaurants, rooming houses, funeral homes, pharmacies, insurance companies, banks, juke joints, and an upwardly mobile African American middle class eager for the latest music, fashion, and style.” The description of Dark Town is reminiscent of Charles Baudelaire’s description of the 19th century Paris street — a majestic and dazzling “tumult of human liberty.” Baudelaire wrote of “the handsome equipages, the proud horses, the smooth rhythmical gait of the women, the beauty of the children, full of the joy of life…” For many late 19th and early 20th century African Americans, the city was indeed Liberty. “South of the North, yet north of the South, lies the City of a Hundred Hills,” wrote W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folks, “peering out from the shadows of the past into the promise of the future…” Dark Town embodied the promises of modern, post-Reconstruction life: economic, political and social empowerment; physical liberty; music; fashion; joy. Amidst it all was Bill Traylor on his wooden crate, an anchored boat in the storm, watching and painting.

“Untitled (Two Dogs Fighting),” c. 1939-1947

And yet, there was a lingering unease. The freedom was fragile, a thrilling and rickety construction built from the shards of trauma and war. 1930s Alabama was far from Utopia. Slavery had been officially over for decades but both black and white Alabamians were living with its ghosts. Jim Crow laws continued to enforce a social slavery over Alabama’s black citizens. The Ku Klux Klan was thriving, creating a republic of fear for Alabama’s minorities. Birmingham policemen killed Bill Traylor’s son in 1929; he was certain it had been a lynching. The Great Depression hit Alabama harder than any other state in the South, aggravating racial tensions. The Civil Rights movement was still decades away. By then, Dark Town would be disappearing. By the 1990s, it was gone.

“Suddenly made fruitful my teeming memory,” wrote Baudelaire, “As I walked across the new Carrousel. Old Paris is no more (the form of a city changes more quickly, alas! than the human heart).” Just as the thrilling modern Paris street was created by demolishing any vestige of the pre-modern France, the freedom of Dark Town was created by ripping one world apart — the antebellum South — and depositing the results, trauma and joy alike, into six city blocks.

•

In 1860, Baudelaire wrote an essay called The Painter of Modern Life. “Modernity,” wrote Baudelaire, “is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immovable.” The modern city needed a very special kind of artist, one that could capture these two elements, the fleeting and the eternal. For Baudelaire, Constantin Guys was just this artist, the quintessential painter of modern life.

An illustrator for newspapers and former war correspondent, the paintings of Monsieur Constantin Guys were a “record of everyday life,” flashes of city life. His decorated women leaned off balconies and gossiped with their legs flopped open, never dropping their fans. Horses and carriages galloped through the streets of his watercolors. He painted the pomp of parades and bored ladies at the opera with equal intensity. Guys had “an intoxication of pencil or brush, almost amounting to frenzy,” wrote Baudelaire. He usually painted quickly and from memory — “a memory that says to every object “Lazarus, arise.’” Constantin Guys was an old man by the time Baudelaire met him, old enough to be obsessed by the lifetime of images that filled his mind. Baudelaire called Guys’ art “mnemonic”.

“Die Loge,” c. 19th century

Guys “loves mixing with the crowds, loves being incognito, and carries his originality to the point of modesty.” The painter of modern life was artless in his artfulness, spontaneous and abundant with his work. He was intensely curious and that curiosity was the starting point of his genius. “To be honest, he drew like a barbarian, like a child… who has taught himself, without help or advice, [and] has become a powerful master in his own way.” Like a child, Constantin Guys took the greatest pleasure in all things, even the most trivial. Especially the most trivial. He possessed an “excessive love of visible, tangible things, in their most plastic form.” Guys was a man of the world, “a man of the whole world, a man who understands the world and the mysterious and legitimate reasons behind all its customs… [He] moves little, or even not at all, in intellectual and political circles.”

The painter of modern life, wrote Baudelaire, is like a mirror as vast as the crowd, “a kaleidoscope endowed with consciousness” an ego “athirst for the non-ego”. The painter of modern life knows sorrow, too, and the sorrow is a lens through which he sees the crowd. “Any man,” Guys told Baudelaire during one their talks, “who is not weighed down with a sorrow so searching as to touch all his faculties, and who is bored in the midst of the crowd, is a fool! A fool! And I despise him!”

Constantin Guys was not like other inhabitants of Baudelaire’s metropolis. He was a soldier who had seen a good deal of life, more instinctual than intellectual but also more aware — if quietly so. Constantin Guys was an outsider and yet, for Baudelaire, he existed more fully in Paris than the other dandies who hung around its department stores and cafes. The aim for “this solitary mortal” was to “extract from fashion the poetry that resides in its historical envelope, to distill the eternal from the transitory.” He was, in Baudelaire’s words, a flâneur. Baudelaire was certain that the drawings of Constantin Guys would become prized by collectors, not to mention historians interested in the real story of the modern street, which was “often bizarre, violent, excessive, but always full of poetry.” Baudelaire’s prediction came to pass, but long after Guys’ death.

Baudelaire’s description of Constantin Guys is a lot like Charles Shannon’s description of Bill Traylor. The two artists shared something important: They were both painters of modern life, both flâneurs, chroniclers of a bustling metropolis coming to terms with itself. Traylor and Guys both painted with and from memory, with the speed and detachment that memory demands. They were old men who lived wholly in the exciting, bewildering modern world — loved it, breathed with it — and yet still belonged to the world that had been destroyed to create it. The paintings of modern life, then, are at once modern and anachronistic. They express the thrills of modern life and also expose it as a façade that hides its past. In the end, the painters of modern life dwell inside modern life and yet exist outside modern life. As such, they are (according to Baudelaire anyway) the only ones able truly to paint it.

Bill Traylor’s oeuvre has two categories of images: People and Animals. The people are sometimes alone but often part of “constructions” and “exciting events.” Sometimes, the people and constructions and exciting events are practically one organism, as in Untitled (Exciting Event: House with Figures). The animals, however, are almost always alone, without environment. According to Charles Shannon, these were depictions of farm animals Traylor remembered from life on the plantation. Thus were the two worlds of Bill Traylor: 19th century rural Antebellum America and modern post-Emancipation urban America, side by side but inseparable, the way they existed inside Bill Traylor.

Bill Traylor belonged to the first generation of African Americans who would call themselves citizens of the United States. His old world would continue to fester beneath the new world for later generations of American Southerners. The new world would dance forward but the trauma that had created it remained. In his Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin — inspired by Baudelaire — wrote about this dual experience of the modern condition: “The street conducts the flâneur into a vanished time. For him, every street is precipitous. It leads downward — if not to the mythical Mothers, then into a past that can be all the more spellbinding because it is not his own, not private… In the asphalt over which he passes, his steps awaken a surprising resonance. The gaslight that streams down on the paving stones throws an equivocal light on this double ground.” Benjamin was talking about the shock effect that modernity had on a generation of Parisians that had grown up in the 19th century. The people of Paris could not fully integrate the “double ground” of these two worlds. Their city was changing faster than the human heart. In 20th century America, there is perhaps no region that has experienced this trauma of living between two worlds more than the cities of the American South.

In an essay about Bill Traylor’s materials, written for a 2012 exhibition at the High Museum of Art, conservationists Susan Mitchell Crawley and Leslie H. Paisley write about the archival challenges that Traylor’s art presents. The unrefined wood pulp of the cardboard is inherently acidic, the charcoal he used smudges easily, the poster paint is a “fugitive to light.” “Bill Traylor’s drawings,” they write, “are their own worst enemies.” Beginning with Charles Shannon that spring day in 1939, the preservation of Bill Traylor’s art — and Bill Traylor’s experience — has been a nearly heroic task by those who have come to love his work. And still, there is something inherent in Bill Traylor’s art that asks us to let it go. The transitory nature of Traylor’s art is essential to it. It’s like Baudelaire said, the eternal is one half of art. The other half is fleeting. The painter of modern life extracts eternity from the moment, but moments are made of forgetting. • 1 July 2013