It takes Satan to bring out the true spirit of Thanksgiving. That’s because it can be hard to give thanks unless you know why you are doing it. Plenitude is lovely. Abundance is a delight. I think of the famous painting by Norman Rockwell. A large American family sits around a comfortable table as the venerable mother carries a moose-sized turkey as the centerpiece. The painting was originally titled “Freedom from Want” and was part of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series, meant to promote the buying of war bonds during World War II. If there is an unsettling message hidden in the Rockwellian sentimentality, though, it’s that these people, this nice American family, knows nothing of want. They are giving thanks for an abundance that is taken for granted.

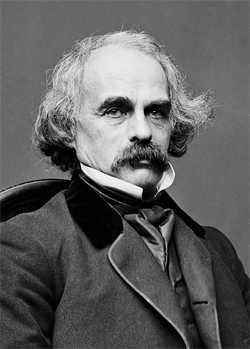

When the devil is on your doorstep, however, thanks takes on a different timbre. The American most consistently preoccupied with thoughts of Satan was probably Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne never trusted in the good times. He saw the devil lurking in every moment of pleasure, waiting for the chance to pounce on the unsuspecting reveler when his guard was down. Hawthorne’s story, “John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving,” is appropriately evil-obsessed. Utterly bleak, it is a difficult fit in the traditional American story of goods asked for, goods delivered, thanks given.

In Hawthorne’s story, a blacksmith named John Inglefield is sitting with his family around the table just after a Thanksgiving Day’s meal. A stern man, he has nevertheless carefully prepared a table setting for his wife, recently dead. Suddenly, the door opens and in walks his second daughter, Prudence Inglefield. We are made to understand that she has left home under trying circumstances, the specifics of which are never explained. John welcomes her, saying, “Your mother would have rejoiced to see you, but she has been gone from us these four months.”

Prudence greets her younger sister and a former love interest, Robert Moore. The scene is tense. Why has Prudence returned? Still, the warmth of the home and the hearth draws everyone together. It was, Hawthorne writes, “one of those intervals when sorrow vanishes in its own depth of shadow, and joy starts forth in transitory brightness.” Suddenly, as the family is getting ready for a nightly prayer, Prudence makes for the door. John calls after her. She hesitates, “her countenance wore almost the expression as if she were struggling with a fiend, who had power to seize his victim even within the hallowed precincts of her father’s hearth.” And then she leaves without a word. The visit home was only a temporary pause. She is called away by “some dark power,” something she cannot resist.

It is a strange story by any standard; for a Thanksgiving story it is stranger still. But Hawthorne was committed to that strangeness in everything he wrote. He wanted to produce an American literature that was deeply moral without being moralistic. It would show human beings as the inscrutable creatures that they are, struggling to make decisions in situations they can never fully comprehend. Why does Prudence come home to the family she has left behind? Who knows, but we have all wanted to go home. When she gets there, something drives her away again. She can’t go back, even though she desperately wants to go back. It is irresolvable. Alfred Kazin once wrote of Hawthorne that “by emphasizing the uncertainty and ambiguity that are attached to human relations, he incorporated into his fictions the strangeness, the ultimate causelessness, which we attribute to human nature as the subject of literature.”

Perhaps, then, Hawthorne is a nice antidote to the blithe triteness that creeps inevitably into a holiday like Thanksgiving (thanks, God, for all the nice stuff!). Gratitude, for Hawthorne, happens under the eye of a creeping evil. Happiness is found only in moments of warmth snatched from the otherwise unaccountable stories of what people do to one another. But in the strangeness of human actions is also the indefinable uniqueness that makes us who we are. Humanness and strangeness are tied together, tragically perhaps, but inextricably. So it is for our strangeness, maybe, that we ought, with Hawthorne, to give thanks most of all. • 22 November 2010