Was there ever a period of time in your life where you took a strange job in a peculiar place, somewhere perhaps far away from your hometown and previous routine? Did you ever return to that place several years later to find that everything had changed significantly? Did you try to track down old friends, only to find they had changed as well somehow, in a way you couldn’t quite describe? Did this make you distrust your memories, as though that period of your life had been little more than a dream?

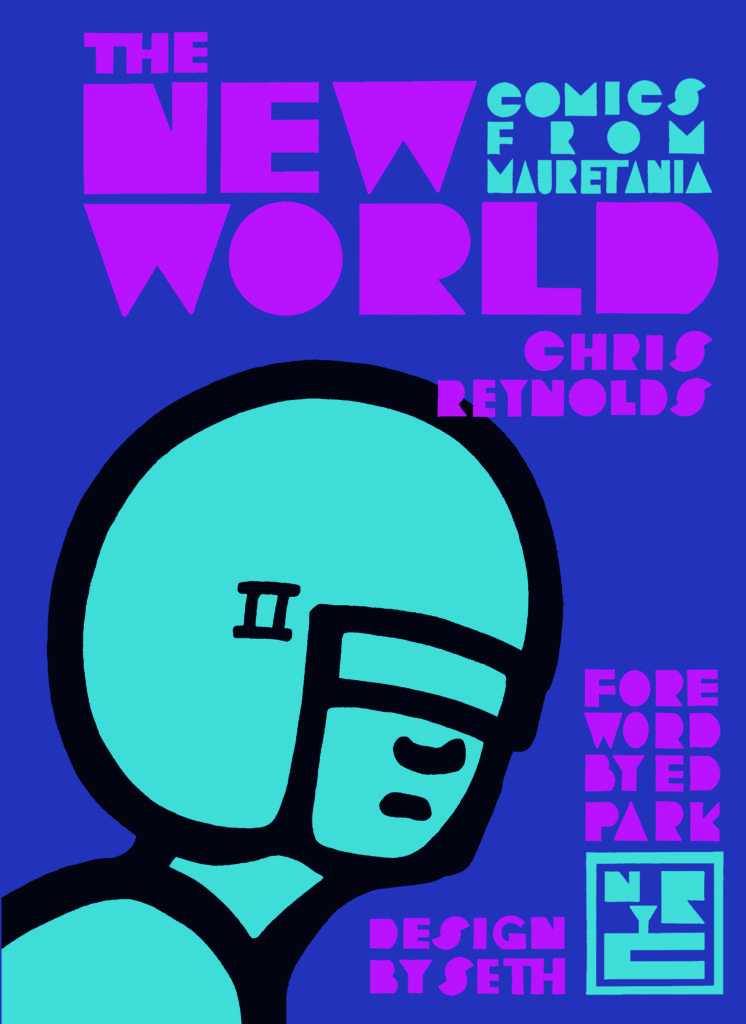

If so, perhaps you were actually visiting Mauretania. Neither the ancient African country nor the ocean liner, Mauretania is the brainchild of British cartoonist Chris Reynolds, who has been producing his own unique brand of contemplative, off-kilter comics since the 1980s. Now several of his best stories have been collected in a handsome new volume curated and designed by the Canadian cartoonist Seth: The New World: Comics From Mauretania.

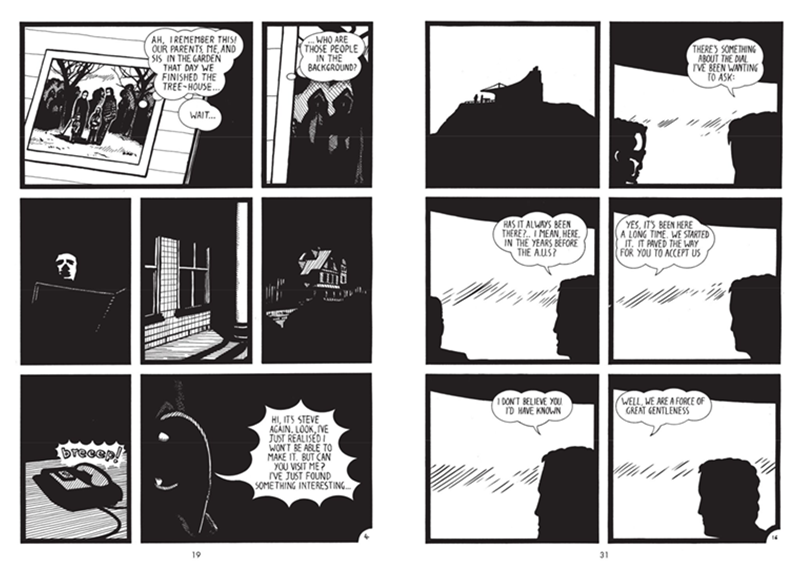

Reynolds’s offbeat, dreamlike structure might best be represented in the lengthy opening story in New World, “The Dial.” Here, a man named Reg returns to his childhood home to find it empty. He goes through old photo albums only to see strange hooded figures lurking in the background. He meets up with his friend, Steve, at a strange church, who tells him there’s been a lot of mining around his house. He goes back and sure enough, there’s now a small strip-mining operation around the home he had just visited. His inquiries with the foreman are met with vague talk about a “gentle” religion known as “The Dial.” It goes on like this for some time — the man wandering, the house and its surroundings changing — until the very laws of gravity seem to be suspended, at least for Reg.

While Reg only gets the one-star turn, there is a recurring cast of characters in Reynolds’s stories, despite the fact that Mauretania seems curiously devoid of people. The most noteworthy one is simply known as Monitor. Perpetually wearing an old-fashioned race car helmet with an M on either side, his eyes obscured by a visor, the enigmatic Monitor roams the countryside taking odd jobs in small towns, bumping into aliens and other oddities and occasionally meeting up with old friends.

There are also the Cinema Detectives, Inspectors Rockwell and Rosa, who chase down peculiar mysteries that don’t seem to have much to do with cinema. When Rosa later disappears, her son, Jimmy, takes center stage, adopts Monitor’s unique style of dress (though he paints a roman numeral two on his helmet instead of an M) and makes it his mission to “close down factories that are ‘harmful’ and that sort of thing.”

Indeed, mysteries abound in Mauretania but are very rarely solved. Buildings disappear into thin air. People vanish or die, only to return years later right as rain, with no explanation. Shadowy groups with names like “Rational Control” and conspiracies abound, but it’s unclear what they want. There is vague talk of a war going on somewhere, but it’s difficult to discern who is fighting whom or what for.

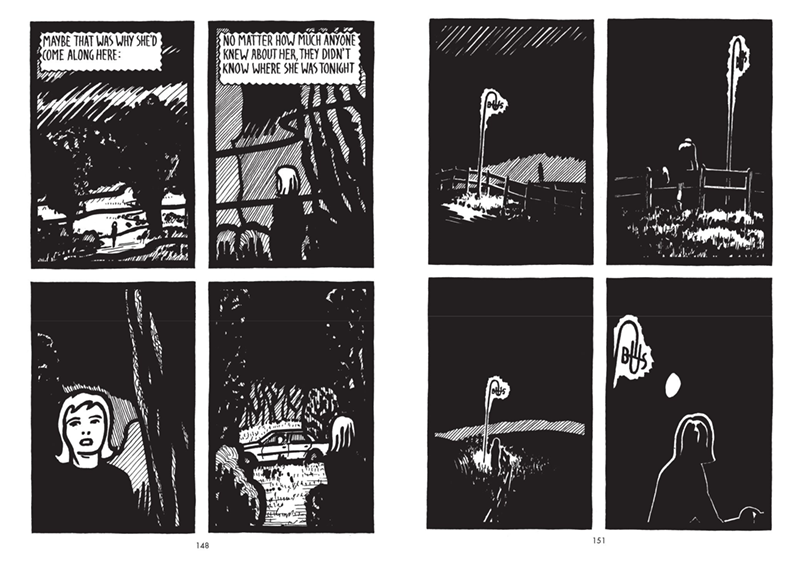

Despite the ominous figures and surreal tropes, however, Reynolds’s stories rarely convey a sense of menace. In fact, the tone is often more bittersweet than threatening. There’s an overwhelming sense of loss that suffuses The New World, of missed opportunities and time eradicating the landmarks that were once held importance to you. It’s not nostalgia, per se, as much as it is an awareness of the passage of time, a recognition that special moments, once obtained, are impossible to return to or recreate.

Which is not to say that there aren’t any pleasures to be found in Mauretania. Reynolds’s characters frequently find joy in simply observing in the natural world or exploring nearby towns and countrysides. The chance that a revelatory moment might come, the realization that the place you had been or job you were doing carried more emotional weight than you initially realized mitigates the sorrow that those moments are over (or will be fading soon). Despite the melancholy, hope for a better world abounds, particularly in the lengthy final story simply titled “Mauretania,” where Jimmy manages to seemingly create a new utopia, “or at least the new world was made while we were there.”

Reynolds’s art style is extremely distinctive. He adheres strictly to either a nine or four-panel grid and rarely — if ever — expands his pages out into a larger spread. His layouts and character design are simple and often spartan. Most notable is his ink line, which is thick enough to occasionally obscure details and sometimes seems as though it will swallow the characters altogether. It’s not a style that should work and yet it does very well, making Mauretania feel suffused in long shadows.

Towards the end of the “Mauretania” story, Jimmy and his friend, Susan, follow a long extension cord for miles and miles, outside of the building they’re in, through the countryside and on for several pages until they come, presumably to their potential utopia. I can think of no better sequence that typifies the central themes in Reynolds’s (who, by the way, is still producing comics) work: Trust your intuition. Follow the nonsensical. See where it takes you. You might be surprised. •

All images courtesy of the publisher.