Melinda Lewis: You took a two-year hiatus from writing after completing your MFA. After finding your incentive or motivation, did the stories just flow out of your brain and onto a page or did it take awhile to get back into a rhythm of writing and editing?

Michael Andreasen: It wasn’t as though a floodgate had suddenly opened, but I did have a new motivation for writing, which made all the difference. Unless you have a lot of experience and confidence under your belt, going from an MFA program to a career in writing can feel like being released from captivity into the wild. Suddenly the answers to questions that had seemed simple – Why am I doing this, and for whom? What’s the goal? What does success even look like? If that success never comes, is this still worth doing? – weren’t so obvious anymore. After a rough dry spell, I got myself back into a workshop with some old friends from the MFA, forcing me to set those paralyzing questions aside and just write, which ultimately broke the witch’s curse. I wasn’t worrying about the cosmic importance of my writing anymore or fretting over its grand telos. I was writing to entertain my friends, and in the simplicity of that act, I rediscovered the joy of telling stories just to tell them. Now when I write, I write for them, and for myself, and never mind the rest.

ML: When people asked me what I was reading, I had a really difficult time attempting to describe it – all the stories feel very present, relevant, but there’s also a lot of play with time. The stories feel very present and not, or futuristic and not. Is this a case of time being a flat circle or just a sense of playfulness?

MA: I try to keep things pretty loose when I’m drafting. Everything is allowed through the door: odd settings, anachronisms, weird out-of-place characters, pop culture references, ghosts, monsters, and here’s another ghost, because why not, it can all stay, whatever gives the story that jolt of energy you need to get it over the finish line.

Then the editing starts, and suddenly you have to examine all of those choices in the cold light of day. For real though, why does this yeoman have a Game Boy? And do I really want this bizarre theme park world to also be a world in which La Quinta Inns exist? Why are there sharpshooters on top of the church? Needless weirdness can be safely culled, but there are those times when it can help solve a problem or answer a question you didn’t know the story was asking.

In the case of the title story, I think the anachronisms keep the us from feeling tethered to a specific period or location, which to me isolates these sailors even more, setting them adrift in both time and space, denying them anything that might provide bearing or direction. If time isn’t providing your story with a sense of stability, then its instability can be just as useful.

ML: I’m sure you can list writers or books that influenced you, but these stories also seemed very cinematic, in a sense. Did you have any visual reference points or have favorite tv shows or films that helped with conceptualizing any of the stories?

Read It

The Sea Beast Takes a Lover by Michael Andreasen

MA: I’m not sure I draw any inspiration from TV (which is not at all to say that I don’t watch way, way too much TV), but many of these stories were born from images I couldn’t shake. The Rocketboy zipping between skyscrapers, the Man of the Future with his blinking diode, Andy the lava giant; each began as a little vignette that blinked into my brain one day and wouldn’t leave.

Sometimes you don’t even remember where you got the image. I was recently doing a reading in Milwaukee where I went to college. The morning of the event, a friend invited me to visit the art museum there. Walking through the galleries, I came across a painting of Saint Francis of Assisi by Francisco de Zurbaran which had been the initial inspiration for one of the characters in “The Saints in the Parlor.” I had obviously seen the painting as an undergraduate and had stored it for later use, but had since forgotten that this museum is where I’d originally seen it. It was a wonderful ambush, and a good reminder that we’re constantly absorbing these images and squirreling them away until we need them.

ML: In a letter to librarians, you referenced that you were at one time “resentful of a nun-heavy primary education.” I’m not sure if that sense of resentment still lingers, but you do certainly seem to have fun playing with the concept of sacred and ritual in stories like “Our Fathers at Sea,” “He Is the Rainstorm and the Sandstorm, Hallelujah, Hallelujah,” “The Saints in the Parlor,” and “Rite of Baptism.” It’s maybe not resentment, but these stories challenge the concept of blind faith and ritual without meaning. What is it about these power dynamics that you find particularly interesting? Because I was super into it.

MA:I was raised Catholic, and a lot of that imagery, language, and symbology still oozes with power and meaning for me. I suppose the stories you mentioned are an attempt to find out why that is. I’m not trying to interrogate blind faith or power dynamics per se, but I do think each of the religiously-oriented stories is examining one aspect of faith that I’m still puzzling over or wrestling with. What it means to follow something you know you’ll never really understand, how faith affects the way we view the people closest to us, why we take comfort in rituals, even ones that seem to have lost their meaning or relevance – these little conundrums are all still terribly interesting to me, and fiction is the best way I know how to engage with them.

ML: Was there any one story that seemed more difficult to write or one that you had to scale back to fit into this collection?

MA: “Jenny” was one we came back to again and again. The subject matter was tough. It started out as just a kind of whimsical story about a girl without a head, but when the broader themes started to emerge in the revision process – assault, shame, resentment of those who obviously don’t deserve it – the whimsy more or less evaporated, and it became about navigating these issues in a conscious and respectful way while also being true to the characters and acknowledging that they sometimes needed to go left when the reader wanted to go right. I also felt the odd need to take care of that brother and sister in a way that I don’t usually with my characters. A friend once accused me of making my characters want things that I have no intention of giving them, and I think there’s a good amount of truth to that, but by the end of that story I wanted to at least make sure these characters were safe, and that, if nothing else, they still had each other. It felt like the least I could do.

ML: I have so many sentences underlined with little hearts: “Morale is in the toilet, and a rebellious stomach cannot help but breed a rebellious heart.” “The smell of the cart has made the bear morose.” “His tongue of flame farts a puff of sulfur.” “We are up to our ears in regret.” It’s not really a question as much as a verbal high five for some of these sentences that just magically appear and feel so satisfying to read. I’m not sure if this comes more so organically or if you spend a lot of time working and reworking until you find the right formula. I guess the question would be — what does your writing process look like? Does a story start with an idea, character, or sentence? Does each story have its own process?

MA: I think as writers we often feel the need to act cool in the face of compliments, but it’s honestly still such a thrill to know that someone else has connected with something you put on the page. Thanks very much for saying so.

To your question: I think each story has to have its own process. They rarely come to me through the same door, and when they do I get suspicious. I’ll start on a story and it’ll sound a little too much like another I’ve written, and I’ll feel myself slipping into the habits of that other story, its language and rhythms. Soon its characters will start feeling like those characters and I know I don’t have anything new and I’ll have to scrap the whole thing and start again.

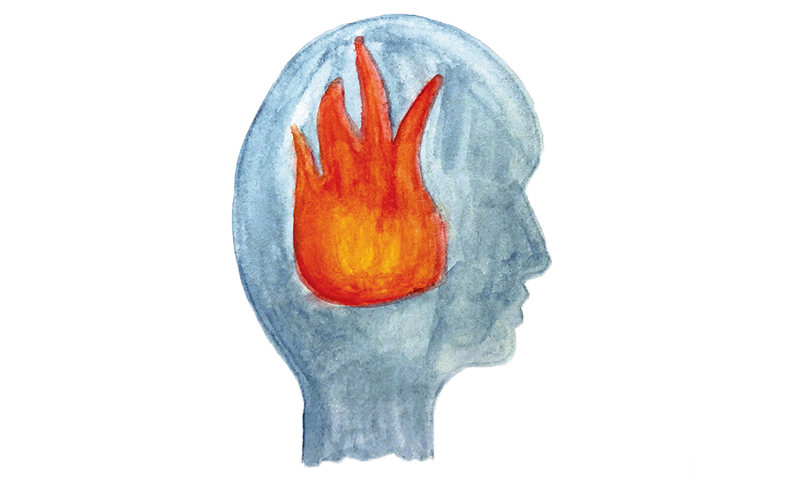

It’s the same when you try to copy other writers; your stories never have the same vibrancy or immediacy as the ones you’re imitating. I had a writing teacher early on who gave us a “write a story in the style of X” assignment, and while it was interesting practice, I think he ultimately did it to show us just how boring and dissatisfying it is to assume another writer’s style or subject matter. We all have to begin there, of course. Each writer starts by trying to steal fire from the gods and get away with it, but that fire ultimately dies if you don’t feed it with your own tastes, tics, and fascinations. This is where the working and reworking you’re talking about comes in. I had another writing teacher who used to steer us away from clichés by saying “Those aren’t your words.” I think about that all the time. That’s all voice is, really. Just trying to hear your words clearly through all the noise.

ML: Reading The Sea Beast Takes a Lover feels like working through a mixtape – there is the flow between stories, there are a few callbacks and perspective pivots when it comes to characters or issues. Did you conceptualize an order while writing or did this come after the fact?

MA: Thank you for invoking the lost art of the mix tape. I’ve used that metaphor myself when I’ve described putting the book together, but the quizzical looks I started getting from my undergraduate students just made me feel too ancient and I had to stop.

But yeah, you try to think of the collection as a set of experiences, and part of your job as a writer is to curate those experiences and arrange them in a way that builds and expands the deeper one gets into the book. I couldn’t, for instance, start the book with “Rite of Baptism” without establishing the religious themes through some of the stories that preceded it, and one might be tempted to read “He Is The Rainstorm and the Sandstorm, Hallelujah, Hallelujah” as a kind of hallucinogenic realism without the other stories to contextualize it. Ordering does more than just present an emotional map, it also provides the symbolic and thematic knowledge one needs to read the map correctly.

ML: This might be akin to picking a favorite child? But is there one story that was maybe more satisfying to write or one that rereading, you’re like “wow! look at what I did there?”

MA: Even though it’s a deep cut, I’ve been reading sections of “The Saints in the Parlor” at signings recently. There are some stories I haven’t even looked at since the book came out, but I find myself returning to that one again and again. I wish I had some thoughtful, artistic reason to explain it, but the truth is I just like those characters. I still think about them, and worry about them, and enjoy their company. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.