Superhero comics love a good analog. Captain Marvel is Superman, but more boyish, and with magic words instead of Krypton. Moon Knight is Batman but with a mercenary past. Watchmen is just a riff on the Charlton heroes. Marvel has Mister Fantastic, while DC has Plastic Man and the Elongated Man. And so on and so forth, ad infinitum.

This is all terribly reductive, of course, focusing on the core extrapolation point rather than what is done with the material afterward. Sure, many times these caped correlations show little creativity beyond tired parody, but there are occasions where, as in Watchmen, they blossom into something entirely different and delightful in their own right.

Take, for example, Copra, an ongoing series, self-published by cartoonist Michel Fiffe since 2012. Copra began as an ode to the late ’80s-early ’90s version of the Suicide Squad. Written by John Ostrander and drawn initially by Luke McDonnell, Suicide Squad imagined a covert government organization that recruited C-list villains from the DC universe to take on missions that offered little chance of survival in exchange for a reduced sentence.

“It was layered, it was nuanced, it was funny and dark and yet so clearly told that even a nine-year-old could enjoy it,” Fiffe has said about Suicide Squad. “It had so many rich characters, a cast consisting mostly of throwaway C-listers who had previously been lifeless, and Ostrander turned them into real people.”

Fiffe initially made a short, small fan comic devoted to the series, Deathzone!. Encouraged by the reaction to that, he created Copra.

At its heart, Copra is a hard-boiled action noir, just one involving people with enough power to level a small city (which — spoilers — happens pretty early on). Like Suicide Squad, it’s a story about a group of ex-cons and assorted misfits — each with a unique ability or superpower — who tackle dangerous and often murderous missions for the government. The first arc (collected in Round One and Round Two) found the team betrayed and on the run. Subsequent volumes (Round Five came out earlier this year from Bergen Street Press) finds the team reformed then splitting up and reforming in various incarnations as new characters join and older ones shuffle off the mortal coil.

Like Ostrander, Fiffe is unafraid to have a high body count. People die in Copra at an alarming rate, often without warning, so it’s probably worth noting while far from exploitive or gratuitous, the amount of violence in Copra means it is not a book for the young or squeamish.

But if you come to Copra with the attitude of “Oh, it’s just a Suicide Squad rip-off,” you’re selling this comic short. Fiffe might have leaned heavily into Ostrander and McDonnell’s work to create the basic framework of his tale, but the end result is more a downbeat, adrenalized and perhaps an even purer version of the same concept. You certainly don’t have to be aware of Copra’s influences, as myriad as they are, to appreciate it.

For one thing, Copra being divorced from its traditional superhero roots gives Fiffe room to go a lot darker. I don’t just mean in terms of depicting blood, violence and the occasional swear word. As other critics have noted, the Copra universe is one devoid of the uber moral good that a Superman or Captain America might represent. As critic Abhay Khosla put it:

Copra is a comic that the Suicide Squad, by virtue of existing in the DC Universe can never be because it is a comic fundamentally suspicious of, derisive of, dismissive of the underlying message of superhero comics: that power can be used responsibly, that our world has space for heroes, that violence can solve problems.

In other words, there are no sunshiney “good triumphs over evil” antics here. Batman isn’t going to pop in to tut-tut everyone’s behavior. Fiffe’s characters are often mean, desperate (but not unlikeable) types who are haunted by vengeance, tragedy, or just plain bad choices. Throughout the series they struggle to come to terms with their demons while remaining alive. Copra’s cast might have superpowers, but they don’t act much like superheroes.

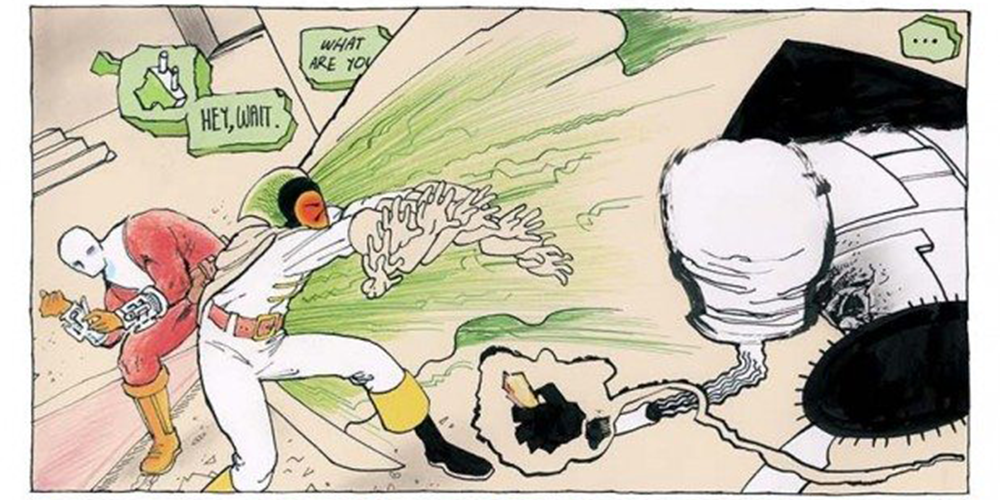

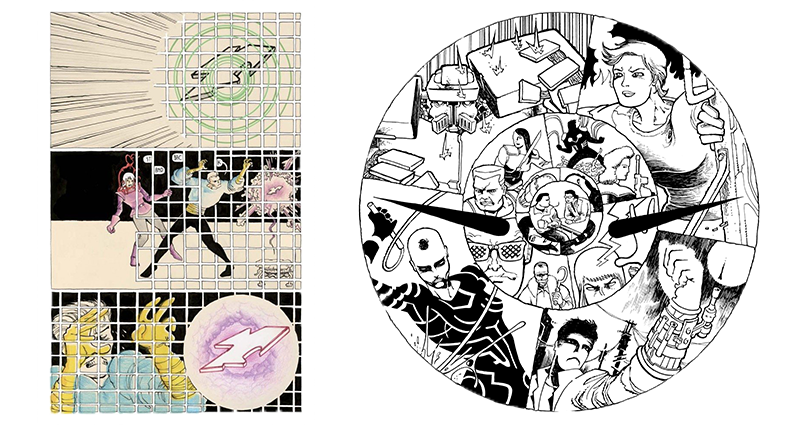

More than this though, Copra seems to be a chance for Fiffe to strut his stuff. Not just in terms of storytelling, character, and dialogue (all of which get high marks) but especially with his art. His character designs pulse with life and invention, sometimes literally as the muscle and flesh occasionally transform into grotesque shapes. Each issue seems to be an opportunity for him to try a new layout, a new way to warp and wind his characters down the page. Fiffe is obsessed with depicting motion, breaking his battle sequences down so they seem like they’re moving in slow, “bullet time” or arranging them so everything appears to be frantically fast. He often distorts things to the point where the action breaks down to pure abstract shapes, only to reform once again into recognizable figures. His use of color is extraordinary.

In essence, Copra is comics qua comics, a superhero story designed not to be some secret movie pitch or possible video game spin-off but to celebrate the possibilities of the medium. There’s a sequence early in Round One where a magician-type character attempts to contain an object of great power. The page divides into a lattice-like structure of little mini-square panels as the character attempts to crane his torso through the gutters to grab the MacGuffin. You can’t have that sort of sequence appearing anywhere but a comic book.

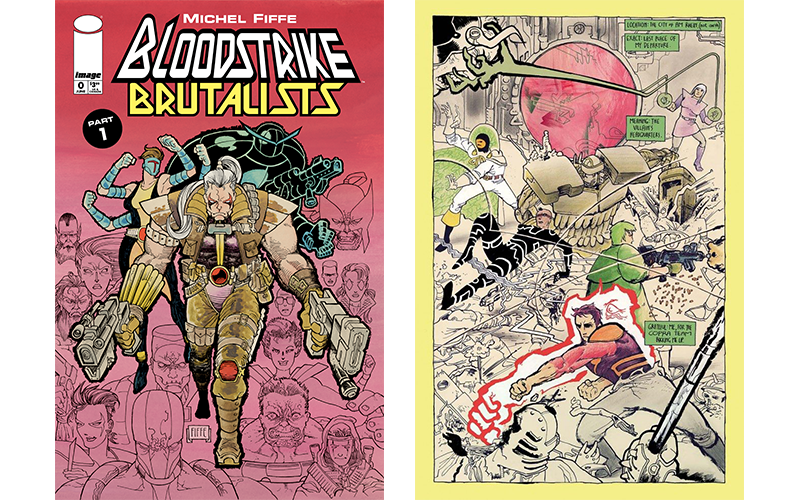

2018 has been a busy year for Fiffe. In addition to the release of the fifth volume of Copra, he also debuted Bloodstrike Brutalists, a three issue mini-series from Image Comics, devoted to an early ’90s series created by Rob Liefeld.

It’s not too difficult to see why Fiffe gravitated to Bloodstrike. Like Copra, it’s another covert government team of hard-bitten superheroes, though in this case they are all literally resurrected from an untimely death to serve the powers that be.

The catch (or hook if you prefer) with Brutalists is that each issue is designed to be a “fill-in” of sorts, providing a bit of behind-the-scenes backstory and tying up some loose ends from the original series.

Which is great if you were a fan of Bloodstrike. I’ll come clean at this point, however, and admit that I had little to no love for the sort of comics Image and Liefeld were pumping out back in the day. To my tired eyes, it just seemed like the poorly written, overly rendered, uber-macho nonsense ill-adept at conveying any sort of cohesive or entertaining story. Artists such as Fiffe have taken lately to re-evaluating a lot of this work, but it’s always left me cold.

More to the point, while Brutalists displays Fiffe’s usual verve and prowess, it, unlike Copra, doesn’t do much to ingratiate newcomers. Brutalists is fun but it’s probably a lot more fun if you’re familiar with the cast of characters. Though it still boasts inventive layouts and tart dialogue, I can’t help but feel I’d be enjoying Brutalists more if I were a fan. Maybe I’ll just wait for someone to come along with the next analog. •

All images courtesy of the author.